I’ve read and studied enough of Ehrman to find his scholarship atrocious… and his scholarship is one of my own worst pet peeves. I addressed one core example on another post, I’ll copy it here if interesting. But in short, he is wrong because he is doing his so-called “scholarship” led purely by his philosophical agenda, and seems utterly incapable of dealing with any actual facts insofar as they would interfere with his agenda. I’m copying it here as an example of how, ahem, “ scholarly” Ehrman is in his treatment of inconsistencies between the gospels…

—————

Here I go on my soapbox again, please forgive me… but perhaps this can illustrate my issue, as it is perhaps the worst example I’ve ever seen… and to make matters worse, Ehrman explicitly calls it his “textbook case” of an irreconcilable contradiction. From Bart Ehrman, Jesus, Interrupted …

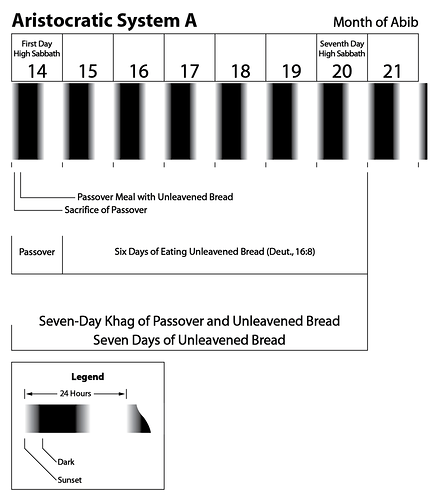

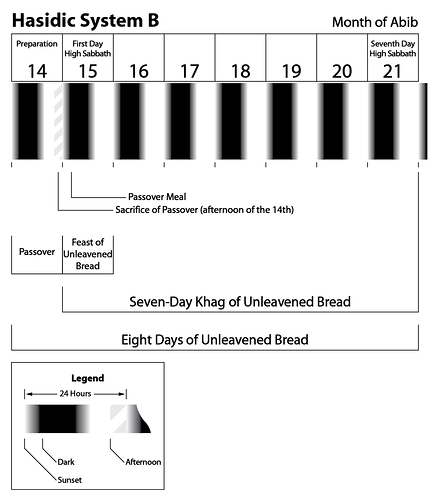

“It was the Day of Preparation for the Passover; and it was about noon” (John 19: 14). Noon? On the Day of Preparation for the Passover? … How can that be? In Mark’s Gospel, Jesus lived through that day, had his disciples prepare the Passover meal, and ate it with them before being arrested, … But not in John. In John, Jesus dies a day earlier, on the Day of Preparation for the Passover … I do not think this is a difference that can be reconciled. People over the years have tried, of course. Some have pointed out that Mark also indicates that Jesus died on a day that is called “the Day of Preparation” (Mark 15: 42). That is absolutely true—but what these readers fail to notice is that Mark tells us what he means by this phrase: it is the Day of Preparation “for the Sabbath”.

Right. And what Ehrman failed to notice is that 16 verses later, John also tells us what he means by the phrase: “Since it was the day of Preparation, and so that the bodies would not remain on the cross on the Sabbath (for that Sabbath was a high day).” (John 19:31).

So Mark has Jesus dying on the day of preparation before the Sabbath, and John has Jesus dying on the day of preparation before the sabbath. Nicely done with this “textbook” contradiction.

This not from some neophyte undergrad student with an axe to grind… this in a published book from the James A. Gray Distinguished Professor of Religious Studies. There just isn’t an excuse for this. Much as I’d like to, I simply can’t find a way to be generous: I’m forced to conclude this is either the height of ineptitude, or downright academic dishonesty. But either way, it betrays an unwillingness to see what even the most casual reader should have been able to see, if he was interested whatsoever in what is actually true. It gives me the impression of someone so desperate to find a contradiction at all costs, it blinds them to being able to read even the most obvious parts of the text.

To borrow from C. S. Lewis… “After a man has said that, why need one attend to anything else he says about any book in the world? … The reader who doesn’t see this has simply not learned to read…Through what strange process has this learned [scholar] gone in order to make himself blind to what all men except him see? What evidence have we that he would recognize a [harmonious account] if it were there? … These men ask me to believe they can read between the lines of the old texts; the evidence is their obvious inability to read (in any sense worth discussing) the lines themselves. They claim to see fern-seed and can’t see an elephant ten yards away in broad daylight. ”

So it is significant to me because when someone makes this kind of error. it calls into question, to me, whether or not I can trust anything in their entire approach. I start to feel like I’m not talking to someone who wants to know what is true, but a person with an agenda intent on arriving at a predetermined conclusion.