Hmmm this is a good point. Can you explain your definition of “methodological naturalism”? I was under the impression it meant an assumption that nothing “spooky” could occur during an experiment, but it seems like your definition allows for things like supernatural events intervening on natural ones (if they could be repeated, tested, etc).

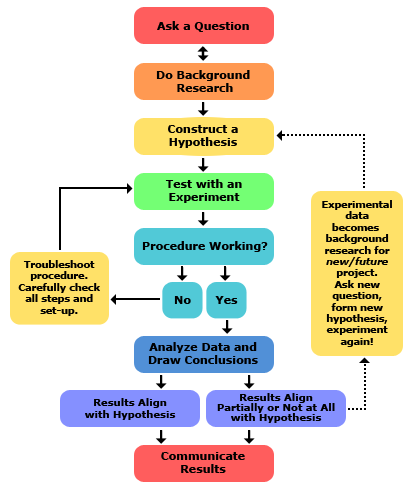

It’s the scientific method.

Perhaps the most difficult part of the method is constructing a falsifiable hypothesis and designing experiments that can test it.

For example, how would we test intercessory prayer? There could be a lot of confounding factors that would have to be controlled for in the experimental design. More importantly, how could we design an experiment to determine if God was the one doing the healing? Perhaps the act of praying allows humans to telekinetically heal the sick without the intervention of a deity. How could we rule that out?

You will also need empirical data. Anecdotes aren’t going to cut it.

Many a scientific theory has started with spooky observations. Even now, many describe quantum entanglement as “spooky action at a distance”.

and @Paulm12

And the problem with something like trying to test the effectiveness of prayer to see if there is a God at action, is that there is no straightforward prediction. God’s answer to heal someone could be “yes”–in which case one would predict that a healing should be observed. But God’s answer could equally be “no” or “not yet–it’s not in my plan for this individual” in which case one would predict that no healing would result after a prayer.

Indeed. My kneejerk reaction was that perhaps even then you might see some statistical variation from a controlled population, but on reflection, you may well not, as healing or not would be an individual thing, likely not reflective in a statistical way. That is, statistically speaking we might predict 20% of a certain cohort might survive a disease, but it would still be God determining which 20%. Of course, that would mean if God chose one person to live, then someone else would have to die to keep the books balanced, and that does not seem right.

This has been my experience as well. It’s not that science can not incorporate what people claim is supernatural. Instead, the way in which believers define the supernatural makes it so that the supernatural isn’t scientifically testable. That doesn’t disprove the existence of the supernatural. It only means that it can’t be tested by science.

It may also be worth mentioning the James Randi Education Foundation (JREF) Million Dollar Paranormal Challenge. All that was required to claim the prize is to demonstrate paranormal activity under the conditions set out by James Randi and company. The only people to take JREF up on the offer (the prize was $10,000 at the time) were water dowsers, and they didn’t do too well.

James Randi’s takedown of Uri Geller was pretty fascinating as well.

Yes, I’d say that science (methodological naturalism) simply can neither affirm or deny that a supernatural action has occurred because it is just not in M,N. toolkit to be able to assess or measure such things (or make predictions about how God “should” act, as if we can put him in a test tube and control his behaviour). As Christy? I think mentioned, it does not mean that M.N. necessarily encompasses all of “truth”.

The yesses would still break the statistical surface. They don’t.

Thanks. I was using “methodological naturalism” to refer to something different, which was a “local” version of ontological/metaphysical naturalism, not the scientific method itself. I agree that things that can be investigated/falsified by the Scientific Method are necessary and sufficient to define science.

I find the Scientific Method (SM) definition allows “science” to incorporate logic and mathematics (one that hardcore ontological naturalism may question). Then again I have a bit of a personal stake in this because while I run many computational experiments, I spend more time in mathematical theory than empirical investigation. I don’t really care much if my research is considered “science” or “applied math” but I do want as much funding as possible so I’m happy to market it as science for grants.

Not sure why one would have to assume they would break a statistical surface. For example, some Christians (cessationists) believe God no longer performs healing miracles in modern times. Other Christians disagree. But it just gets to the point, that one’s concept of what God “should” do is so squishy that it cannot not provide a consistent prediction in a controlled experiment.

Oh…and I’m chuckling a bit here… one could argue that a biblical command was “Do not test the Lord your God”. And so, any attempt by humans to design an experiment to force God’s hand would simply be ignored by him, as a matter of principle?

I read up on one of those double blind prayer experiments. They had hired random people of all different religions to pray to their preferred divinity on some call in phone line. Another hired “healers” to send “healing thoughts.” Most Christians I know would not have even considered what was going on intercessory prayer and it wasn’t directed at Yahweh, the Judeo-Christian God. So what exactly they think these studies “prove” is beyond me.

If they happen, they will break the statistical surface. If the statistical surface isn’t broken, they didn’t happen. You questioning that is hatstand.

I agree. If they don’t break the statistical surface, they didn’t happen. But the point is that a null result “nothing happened” could still be taken as evidence by theists that there is a God who chose not to act.

Never mind the studies. What about the stats?

To be honest, I thought the same thing. If I was God (thank God I’m not) I don’t think it would be productive to do answer such prayers under this type of scrutiny. Perhaps I’d always leave the results so there was some element of doubt either way. You answer one experiments’ prayers, and then you have all these follow up calls about how effective, to whom, when, etc. I don’t think God is looking for us to just ask him for stuff and not play our own part in helping if we want it done.

There was a time when I was a kid (maybe 6) I once tried to “trick” God by saying if he was real, he should let me win this raffle which had an Xbox (which of course I wanted). I was disappointed when I didn’t win. In was later that I realized it was a very good thing I didn’t win that Xbox. I personally believe God wants more for us than just the material stuff we think is going to make us happy. Perhaps this is why I find prayer to be the most effective for me when it is to help me remove my own judgment of others.

Yeah, I think the way many of these experiments are set up is pretty poor TBH. If they show a positive result, sure, you learn something. But if they don’t show any conclusive statistical result it doesn’t really rule much out. In my (controversial) view it’s a waste of time and money. Plus negative or inconclusive results don’t always get published as much so there’s that too.

Plus, maybe as Christians we should pray for sick people out of obedience and reverence for the Bible, which tells us to, and because we believe God answers prayer based on our experience loving and being cared for by God, not because a scientific study says prayer is effective.

Just for @Klax and any statisticians lurking out there who might be cringing at my glossing over of statistical terms I should add a nerdy explanation about “breaking the statistical surface”, based on my statistical training: (feel free to ignore since this doesn’t change the overall point, I don’t think).

The level of statistical surface that needs to be broken will depend on the parameters set in the statistical model (by convention this is usually set at alpha = 0.05). However, failure to reject the null hypothesis of “no effect” cannot be interpreted as “proving” the null hypothesis. In other words, technically speaking, if the statistical surface is not broken, one can not say that “there is certainly no effect”. The strength of the conclusion that there really is no effect will depend on what is called the “power” of the statistical test, which, in turn will depend on such things as sample size, the expected effect size, and the degrees of freedom in the model.

The power of a statistical test will increase as the sample size increases, and if the expected effect size in the experiment is large. If the statistical surface is not broken in this situation (in a test with high statistical power), then one can be increasingly and increasingly more confident that “there really is nothing but noise” going on in the data…, i.e., acceptance of the null hypothesis will increasingly asymptote to 99.99999999…% probability that concluding “there is nothing there in the data” is the true conclusion.

Given the outstanding number of eyewitness claims for miracles, some of which are fully documented, it’s hard to believe the results from any experiment could completely outweigh that something happened.

I found this quote relevant in Keener’s book Miracles Today:

If you are going to dismiss this testimony, Hume says (implying “and you should”), then why not be consistent and dismiss them all? Rather than such an all-or-nothing approach to witnesses, which would undermine all legal reasoning and historiography, a sounder way of handling the evidence would have been to acknowledge that the evidence does in fact support Perrier’s healing. We can come up with a nonsupernatural way to explain it if we wish, but merely dismissing inconvenient evidence is not a fair way to argue.

Hume’s argument depends largely on his dismissal of sufficiently credible eyewitnesses. As we shall see, however, this argument does not work today; there are simply too many credible eyewitnesses now.

At the level of an individual case (anecdote), I suppose there will always be disagreements among people over whether a miracle occurred because each person comes to the table with a different philosophical presupposition about the likelihood that (a god) will act.

In the process of trying to deduce “the most logical explanation” for an event, for a committed atheist, the miracle hypothesis has a simple probability of zero, and so any natural explanation, no matter how unlikely, will ALWAYS have a higher probability compared to the miracle hypothesis.

Agnostics and theists, however, will place a non-zero value on the probability that God could act, and so when they weigh natural explanation hypotheses for an event against the miracle hypothesis, there may be some point at which the natural explanation becomes so improbable that they conclude (in the words of the author " When you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth. – Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, stated by Sherlock Holmes

I note, however, that it’s not as clear as the Sherlock Homes quote suggests, because natural explanations are never “impossible”…they may just reach a threshold of being very very very very improbable. But what constitutes “improbable” in comparison to a miracle option will depend on one’s philosophy/worldview about god(s).

Keener makes a helpful analogy between miracles and whether a person has long or short hair.

Sometimes a perfectly explainable natural phenomenon that exactly coincides with prayer can fall into the grey area. That is until it doesn’t and George Mueller’s credibility must be suspect for the ‘atheist’.