Start with the “quotes” that I linked to. Please correct me if you think I exaggerated anything.

- Don’t overestimate my background, thinking or thoughts.

- My message formatting–as novel as anyone and everyone finds it–“really is and always has been” for me. I started out, around 2005, with the increase in lengthy digital communications, outlining stuff, and transitioned quickly to bulleting stuff.

- Christian apologetics of any kind is relatively new stuff to me [circa. 2010+]; however, I have been woefully uninformed as to "the kinds or ‘schools’ of apologetics. The “taxonomy” that I sent to you previously was the “best” that I had ever seen. I found Penner’s reference to Steven B. Cowan’s book,“Introduction to Five Views on Apologetics”, ed. Steven B. Cowan (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2000), 7-20 [Penner, Footnote 35] useful, although I’d prefer to see it “bulleted” and formatted differently.

- At this time, I continue to appreciate my previous tutor’s introduction to secular (agnostic atheist) views regarding “knowledge”. (Cf. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1v-RSJfFlNfK9o36TX8hphvUftWWABVsa/view?usp=sharing).

- I’m not prepared to and won’t offer a Penner-ian view of that thoroughly atheistic position here.

However, I’m sure that the atheist that I once knew would not be swayed by anything, if anything, the Penner-ian had to say. Although my atheist acquaintance would have been capable and more than willing to discuss almost anything else the Penner-ian wanted to talk about. - There’s no doubt in my mind, though, that a Van Til-ian would reject the atheist position and any Penner-ian response short of “a call to repentance”.

I, on the other hand, am still searching–as I write this–for way to reconcile something from my atheist acquaintance’s position to the Van Til-ian “fundamentals” on paper, so to speak, since my atheist acquaintance has “crossed the river Jordan” and there’s no Van Til-ian I know that I could bear talking with about how to go about reconciling the atheist position with the Van Til-ian fundamentals.

Given my absent acquaintance’s belief in the importance of “propositions”, I doubt a Penner-ian would be able to help me reconcile both positions.

This is another “Round Up” post, rather than publishing a bunch separately.

Emailed Articles From the Author Himself:

Myron Penner emailed me two of his articles that comprise part of a dialogue between him and Brad Seeman regarding The End of Apologetics. Because Penner mentioned me sharing the articles with people, I believe that is tacit permission to share them. I have saved them to my Google Drive and would be glad to send the link to anyone who PMs me, asking for them. I don’t have Seeman’s articles, but they would something one could acquire through an interlibrary loan request. Penner mentions the citations in his articles.

Edification and Richard Twiss

Throughout this book, Penner mentions sources of edification broadly, and particularly in relation to the local church and the universal Church.

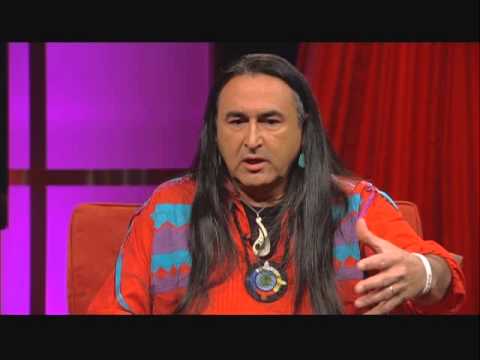

Because of this, Richard Twiss has been on my mind often. He was a Lakota follower of Jesus and talked without reservation about the problem of our enculturated views of Christianity. Here is a link to a video interview with him, where he talks about what it was like for him to be a new Christian and a Native American. His wisdom is profound and convicting. The link will start you where he talks about it. (another time stamp of note is 21:20, where he talks about Colonial Christianity):

Terry: Tamer Reformed Calvinists and the Atheist Tutor

@terry_sampson, I just want to make sure I understand the significance of the quotes you pulled from this article? It seems like you are pointing out the similarity between Penner’s call for a lived out faith, and the early church’s practice of living out their faith as well.

Do you see differences between the practices and/or the thought behind the practices? How do/would the ROWDY, hard-core calvinist types you mentioned earlier see this kind of practice, do you think? Lots of questions. Please tell more about your thoughts on the quotes from Timothy Paul Jones.

I’ll try to get to your many other shares soon, but time!I did glance over the piece on “knowledge.” [quote=“Terry_Sampson, post:751, topic:49565”]

At this time, I continue to appreciate my previous tutor’s introduction to secular (agnostic atheist) views regarding “knowledge”.

[/quote]

These last few sentences are eminently quotable:

Within the realm of attempts to describe the physical universe, not much attention has been applied to the issue of the difference between a statement and a proposition. A statement is just a grammatically well-formed formula that has no free variables. A proposition is a statement that has meaningful content. Unless one is merely playing some formalist game, it makes no sense to say of a statement that it is true or that it is false unless the statement of which one is thus speaking is a proposition. It is my opinion that twentieth century science consists almost entirely of word salads that could not possibly be true propositions because they are not propositions at all.

Looking into Chapter 5

I started my “preparatory reading” of Chapter 5 (abstract of the chapter from the book intro, and then conclusion of the chapter). He will be addressing this binary choice directly, in case you are interested in continuing with the book and dicussion.

Tangents: Library Research on Apologetics

Since starting this book, I have been interested in looking into longitudinal studies regarding the effects and/or effectiveness of the modern apologetics movement, if such data is even being collected, much less scrutinized. I reached out earlier this week to about 10 seminary libraries and so far have heard back from 6 with research suggestions, resources to hunt down and a few articles, and a 7th asking for clarification of my question. So far, no one has said, “here it is.” I now have many things to follow up on—after we are done with this book. It’s interesting that every answer I received was very different. I’ll be visiting a few campus libraries in the near future, I think. Research Road Trip!

Chapter 5

Starts Monday. It’s good to be through the really heavy theory. I think I will end this book with one of my enduring questions: How? But having the underpinnings for a different way to view What? and Why? is a good start.

Favorite quote from the video (a little after 18 min. in), when “Mr. Twiss” (I can’t reduplicate his Lakota name here) was speaking of having his seminary students participate in a sweat lodge ceremony:

“Apparently Jesus and the Holy Spirit don’t know where they’re not allowed to show up.”

-Merv

Contrary to what the self appointed theological overlords believe when they cast a couple scripture in favor of their our own opinion, intended purpose makes all the difference according to Penner. Self righteousness violence on behalf of a deity that doesn’t roll that way can never be holy. And violence done to others leaves the deepest mark on the one who strikes the blow. Ironic.

Merv, thanks for watching. Excellent choice of quotes.

I read Twiss’s book “One Church Many Tribes about 20 years ago, and then he spoke at our church. This interview is a good synopsis, but the book goes into more detail, of course, particularly in regard to the insane level of interference “dominant christianity” has put in the way of those who would believe. I think about this in regard to other legitimate forms of Christian expression, like Black churches in the U.S., where the theology is treated as suspect or deficient by “us.” “Theological overlords” as @MarkD has called them.

The Church is rich and vibrant and there are parts with a wonderful witness of Jesus. How valuable it would be for us to learn from them, to be edified by them, and even see them as part of the same church universal.

Yep.

Those intended purposes are also tied up in how we understand that person in front of us, WHAT we understand that person to BE.

It’s not enough to tell ourselves we’re trying to save souls, if we really don’t even “see” the person. And disrespect and coersion are not effective evangelization tools, not edifying (up-building). At best, I think, they create resistance to anything of value in the message.

Here are the excerpts from a podcast called Econtalk whose transcript I read yesterday. The interviewer is economist Russ Roberts and his guest is Iain McGilchrist. Sorry it’s a bit long. I’ll go through and bolden the parts which I think reflect Penner.

1948, Paul Samuelson writes The Foundations of Economic Analysis, where he mathematizes and linearizes, more or less, economic life. And it starts, say, a trend, say, in seeing the economy as a system of equations. As something to be manipulated. As something we have mastered. As something that is precise. As something that is controllable. And so the change goes from a bottom-up perception, which tends–which is, almost by definition to be observed–to a top-down one, which is to be, then, controlled. And the economist then sees him- or herself as an engineer/priest–a priest/engineer that can manipulate the human beings. Ironically, Smith warned against this in 1776. Excuse me, in 1759, in The Theory of Moral Sentiments. He talks about the man of system, who thinks he can move the pieces of humanity and society around like pieces on a chessboard, forgetting that they have emotions all their own. So, in economics, I see the metaphor you are using very powerfully. And, so many economists see the world in your left-side way–what you describe as the left side. Which is, ‘I know. I’ve got this. Let me do this. We know how to do this. We know what the minimum wage should be. We know what stimulus package we need to pass. It’s a little–it’s short by $234 billion dollars.’ And your point is that, that’s a deep misreading of what science should be, just as it is in many other applications. I would–you know, I harp on endlessly here on the program: epidemiology and other medicine–that the complexities are not controlled. We don’t understand them. And yet, people, you know, go around as if they have all the answers. And it’s very–I think your way of seeing it is very powerful. And I would just close with one thing on this; and then let you respond. But, of course, then I say to myself, ‘Am I just kind of smugly dismissing their smugness?’ You know: ‘I’m so smart; I know how smart I am. They’re so dumb they think they are really smart.’ And so, I start to think, ‘Maybe–I’m not so sure how to balance that out.’ But, anyway. React to that.

Iain McGilchrist: Heh, heh. Well, my reflection on that it is not what you think. It’s the how, of how you think it, that matters. As, it’s not what you do but the manner in which it is done and the reasons for which it is done and the mentality with which it’s done that changes it. So, you may be right that they’re missing something without necessarily being smug about it. I think the degree of humility is what’s missing from many of the crasser areas of physical science and social science.

Now, I know next to diddlysquat about economics and the world of finance. So, I was surprised by this. But of course having talked to them, I see exactly why they say that. And so I find myself being invited by people in the world of industry and economics to enter into a conversation. I think I could illuminate a little bit–you said–or perhaps you don’t want me to address the question: but you did rather provocatively say, ‘I’m not comfortable with this idea because a culture doesn’t have a brain.’

36:47 Russ Roberts: Yeah. Talk about–respond to that.

Iain McGilchrist: Yeah. I mean, the thing is, I think there’s a bit of a misunderstanding here. I’m not saying that, as it were, 'Something has happened in the brain and it’s controlling you or controlling society.And you see it happening in the history of culture. That’s really what I was aiming to show. I wasn’t suggesting that if you scanned people 500 years ago, you’d find different things lighting up in their brains, so to speak. That is not the point. My point is that we can get blinded to certain things by custom and by the way in which our culture talks. We can learn to ignore things that our brains are fully equipped to tell us but which our culture tells us we shouldn’t listen to. And so, we can develop what in my view is a very simplistic, impoverished idea of the world–simple, predictable, mechanical, controllable, even perhaps complex as it gets underway, but nonetheless by routes that are effectively predictable and controllable. Or, you understand, that we don’t know a tenth of what we are dealing with, and that these systems are intrinsically, not accidentally but intrinsically predictable. And that the fool is the person who thinks that they know it all and can control it all.

I’m late to the party and 700 posts behind…

Tell me what you really think…

What is the status of Christian thought if the apologetic foundations of Christian discourse are abandoned? Or, to ask the question differently, what does faithful witness to Jesus Christ look like in a postmodern context? I cannot expect to address these questions exhaustively and in all their complexity.

Does he at least address them? it would be utterly disappointing to see apologetics bashed on for a few hundred pages with no alternative provided.

Postmodernity is a condition, or a set of attitudes, dispositions, and practices, that is aware of itself as modern and aware that modernity’s claims to rational superiority are deeply problematic.

What is it about modernity that is not rationally superior? We have science which means our understanding of physical reality is certainly on better footing than anyone else in history. He doesn’t seem interested in the question:

Rather than arguing for the superiority of postmodernism, I assume post- modernism as a starting point and try to make this standpoint intelligible . . .My goal is to reorient the discussion of Christian belief and change a well-entrenched vocabulary that simply does not work anymore, whatever its past uses might have been.

The end of chapter one I put on my website. I write for myself as much as others.

I am writing this book from the vantage point of a member of the Christian community—the church—and I write it for my own edification as well as that of the church catholic. This is therapy as well as theory. I trust it will be obvious that, while I am engaging in a polemic against a certain form of Christian apologetic discourse, my ultimate goal is to open a pathway for faithful witness, not to close down its possibility.

Chapter 1 was an interesting intro but fluffy, no meat yet.

The proper ground of our knowing Christianity to be true is the inner work of the Holy Spirit in our individual selves; and in showing Christianity to be true, it is his role to open the hearts of unbelievers to assent and respond to the reasons we present.5

I can empathize with Craig here but lately I think it underestimates God but also at the same time, shouldn’t our faith be rational, or consistent with what is known to be true about the world?

Penner: What also strikes me is that Craig’s apologetic paradigm conceives of truth, reason, and faith solely in terms of the modern epistemo- logical paradigm.

Is that a bad thing? If someone asks us how do we know the Bible is true? How do we know Christianity is true? How do we know Jesus rose from the dead? Are we supposed to chastise them and inform them they are mistakenly asking that question from the perspective of modernity. Tell them we don’t believe in silly notions like “facts,” history or science? Do we tell them “The truth of the gospel is [not] made evident by its conformity to modern standards of rationality.”

And this is due in no small part to his conviction that being a Christian amounts to giving intellectual assent to specific propositions?

This posture is both correct and false at the same time in my eyes.

Since modernity has rejected the premodern idea that the universe is structured by an inherently rational principle, there has to be some way of connecting the human rational mind to the brute universe. Premodern thought is more inclined to understand the human mind as encountering or participating in the world directly, without anything mediating it.'8 This is possible, as we just saw, because the mind and reality are similarly structured by 1pgos. But in modernity this tends to happen in the form of propositions that express “facts” of the universe, which are thought to be objective features of the universe.

Apparently I am not smart enough or too steeped in modernism to understand any of that. It is entirely unintelligible to me.

What Craig fails to see, however, is that his (conservative) agenda is defined just as much by modernity as the “theological rationalism” he opposes— and is every bit as complicit with its assumptions. Of course, there are substantial and important differences between conservative and liberal theologies, but their disagreements belie a common commitment to the modern paradigm.

This was very well said. But can’t the same be said of this book I am reading which I think at some poi tis going to reason and argue against apologetics?

Postmodernism, Moreland concludes, is “immoral and cowardly” and a form of intellectual “pacifism” that lacks the courage to fight for the truth." Instead of fighting the good apologetic fight for truth, knowledge, and the Christian way, it "recommends play- ing backgammon while the barbarians are at the gate."46 Moreland therefore deems postmodernism antithetical to the gospel and believes Christian apologists must do all they can to defend the faith against it.

Ouch! I honestly don’t know where I stand on this issue. I am strongly influenced by modernity and my studies of science and history lead me to the idea of objective reality and facts.

For all intents and purposes, then, the modern apologetic paradigm is deeply embedded in the epistemological paradigm of modernity—it shares its goals, its questions, its basic methods, and, even more im- portant, its practices. That is to say, the Christian apologetic paradigm shares the philosophical horizon of modernity and is thoroughly im- mersed in its ethos. This ethos of modernity is defined by secularity, in which the existence of God is not intuitively plausible and the reasons we have for believing in God—or anything else—must be objective, universal, and neutral. In fact, in the modern imagination, justifying our beliefs in this way is the fundamental philosophical concern. The driving need to prove the scientific viability of Christian beliefs, the rational superiority of the Christian worldview, or the so-called case for Christianity signals an underlying preoccupation with mastery and control through rational dominance and a conviction that modern systematic theology done well yields the most enlightened form of the Christian faith. Despite what Christian apologists may tell them- selves and others about how much they oppose modern philosophical assumptions or the dominant views of modernity, they nevertheless are in fundamental agreement with modern thinkers about which questions are the important ones, how those questions need to be answered, and why they need answering.

I sure hope he provides a “reasonable” alternative…or is that me being too modern?

Still no meat yet. Off to chapter 2.

Hey Vinnie!

Welcome. There is definitely plenty of reading to catch up on. I recommend digging into the book mainly, because that’s the meat. But other people have stuck to the discussion. The book is very time-consuming. I have found it a greatly rewarding use of my time, however. I hope you find your engagement with it of value.

You will not be disappointed.

He does address them, but not as exhaustively as I would wish. However, if he answered all of my questions the book would be unreadable. Much of his answer to your question is interspersed throughout the chapters, and the 5th chapter pulls a lot of it together in one place.

He will address your questions about the differences between modernity and post modernity. His arguments regarding these differences are very heavy on theory. There are quite a few links in the Resources Slide you may find helpful, depending on your familiarity with pre/-/post-modernism.

He is. He will address it probably differently than you might wish, but in a way that is meaningful and appropriate.

Just wait. Read on.

All I can say, is keep reading. Expect Penner to greatly challenge what you think, if you are a proponent of apologetics.

Keep looking for further points related to this, the nature of Christianity in relation to propositions, and Penner’s description of precisely the content and role of propositions in Christianity.

This is hard reading. I’ve read the first 3 chapters at least 3 times, and some sections more than that. The resource slide has a few things that go over the differences between modern and premodern thought. I also put together a table of points just lifted out of the book for my own notes, but shared it in Slide 61. It’s not elegant or polished, but it might help.

Just trying to help with the bit you quoted directly above:

This is a key point that will help you interpret the rest of the section.

Penner will continue to return to the differences between premodern and modern thinking. Looking over the resources I mentioned, though, will help you become more familiar with the ideas so that his points stand out more to you. There is also a good deal of discussion about this section earlier in the thread, usually including page numbers, which should help. So you can see how we all hashed it out weeks ago.

Yes, he will reason and argue against apologetics. That has been a major complaint about the book in articles as well as in this thread. I think there is an essential difference, however, between the things (Christian belief vs. theory of apologetics) being argued or defended.

As you know, apologetics is a defense of Christian belief, the ultimate goal of which is that the hearer is eventually lead into a personal relationship with Jesus Christ.

Apologetics theory is the thought behind HOW apologetics should be carried out, the content, etc.

Penner argues against a particular theory of apologetics, which he attempts to show leads to something other than faith in the person of Jesus Christ and a personal relationship with him. He does NOT argue against seeking a way to promote faith in and a personal relationship with Jesus Christ. He is actually seeking to find a method of doing this that achieves that goal.

Keep reading. Penner works hard to make a case that matters of faith are simply a different kind of thing and are demonstrated effectively by completely different means. He eventually DOES come back to the use of reason, but differently than is used in the modern apologetics paradigm.

Get ready!

Vinnie, I’m glad you’re here and reading. I expect there are going to be parts of this book that you really hate. I hope, in spite of that, you stick with it and try to really get at what Penner means to say, rather than the superficial representation I read in some of the responses by apologists to the book. It is a really had read. It is worth it. And even if you don’t agree with his analysis in the end, he makes some important points that any apologist needs to take to heart, when thinking about what they are actually doing, when they are attempting to introduce another person to our Lord Jesus Christ.

Ask away. Also read around.

If you have questions about where things are or how to find things, feel free to contact me.

If you’re looking for a good, rationally compelling argument about why you need to move away from modernism toward postmodernism, then that’s just modernism continuing to be your tour guide - and ready to appraise and value the next philosophical system that comes along (like ‘postmodernism’).

I think you’ll find that Penner does a pretty good job of trying to model his own stance - by not playing that game any more - which of course our inner, very rationality-minded tour guides find frustrating.

But it’s also important to note that Penner isn’t trying to leave rationality or argument - and certainly not science all behind. He isn’t saying those things have no place in Christian discipleship. He’s only claiming that they should not be the unquestioned juddges, arbitors, or gatekeepers if you will, for everything, including - and this is important - all the higher questions of life that typically have importance beyond what is scientific or empirical.

You are right that science has shown itself to be our best tool for our physical understandings of life and cosmos. But it (and the human rationality that supports it) are not our only - or even our best tools for answering questions of meaning, beauty, ethics, or love. Reasoning and argument of basic sort must be part of all this discussion, obviously, if we are to read or discuss anything at all; but Penner is aware of the irony of trying to go completely down that road yet again (which is just to continue blindly with modernist agendas and methodologies). It’s a challenging balance to achieve.

[Maybe another way of putting it is this way: Apostles are certainly free to make use of reason, as Paul indeed does, but his main appeal is not to be clever and so appeal to clever people. It’s to be an apostle that points people to Christ, rather than worldly cleverness. One can make limited use of rationalisty, and even strive to be rational without needing to make it king of everything.]

I think faith should also be consistent with what we know or can about ourselves. If we import external criteria and apply them pell mell to ourselves we will be objectifying our understanding of our subjective experience which is every bit as absurd as it would be to seek to understand the objective world by way of subjective standards. Distortion ensues in both directions.

CHAPTER 5 DISCUSSION BEGINS TOMORROW

Last edited: 8/21/2022

I’m looking forward to the discussion.

There are many contexts in which this is true, aren’t there? It’s hard to “step outside ourselves” to get a different perspective and look for what we’re missing. It’s easy to be stuck in our thinking, because it’s what we have always done and it’s supported by everyone around us.

Before we leave Chapter 4, I wanted to revisit a few quotes:

One of the questions I have wondered about since Chapter 1 is what kind of “apologetic” is left, after Penner demonstrated the impossibility of the modern paradigm which seems to be so popular (here and now). I think he fleshes the answer out fairly well (at least at a theoretical level) end of this chapter:

The first part consists of the level of truth we can honestly attest to:

Whatever the case, if we really are not concerned about achieving the (absolute) Truth as God sees it, if we really do not believe that achieving the Truth is necessary to attaining normative Christian truths, and if we further configure our thinking about Christian truth around edification, then it seems to me that we will have the ability to attest to the contingent, fallible truths that edify us. In our Christian witness we always testify-as Luther does-from our conscience and not from an epistemically secure and objectively demonstrable position. The Christian witness says: “Here I stand. I cannot do anything else. I cannot refuse to acknowledge this truth, because it is the one that is true for me and has shaped me into the self I am.” (pg. 126)

The second part is the absolute necessity of “a dramatic portrayal of how things may be when the rule and reign of Christ is expressed in and through our lives.”

Truth telling is a process of attesting to the truth of our convictions. It is not a snap shot of reality but more like a dramatic portrayal of how things may be when the rule and reign of Christ is expressed in and through our lives. Christian truth is an aleitheia-an uncovering, disclosing, or making visible the very presence of God among us. And this uncovering is concrete and actual, not abstract and intellectual. Christian truth-telling, therefore, is a field of performance and an acting or living out of the truth that is edifying and upbuilding. This is not merely an objective apprehension or formal acknowledgment-we must win these truths for ourselves and make them our own. It is not an instant calculation that is over and then done with, but the undertaking of a lifetime. (pg. 127)

In summary, Penner says:

The faithful expression of Christian witness comes in the form of both word and deed (and only in this bivalent form). We can never show the light of Christ and the truths that edify us except through our words and actions-and in an important sense these truths do not exist for us or those to whom we witness apart from our full testimony. We will not have the truths that edify us, nor will we be a witness to them, apart from our fully assuming them and living so that they shape our words and actions.

As demanding as modern apologetics engagement is, Penner’s proposal is much more so. Christians, all of us, as living interpreters of the texts and experiences we claim to find truthful and life-transforming, are demonstrating that hermeneutic every single day of our lives. Actually, we already are, always have been. And people are reading US as texts. We are not engaged in a scheduled, timed debate with a mic cut at the end, but the day to day performance of what we actually believe to be true about Jesus Christ. That is our testimony, or attestation.

Those stakes seem much, much higher to me.

Ain’t that the truth!

So when you quote Penner…

Not only does this not remove the wind from the sales of ambitious apologists … it adds more!

That is, if somebody was hoping to read Penner thinking to themselves - “Yeah - I like to hear confirmation we shouldn’t be verbally pushing our faith on other people because I think it’s better to show my faith by how I live” - Penner’s quoted response lays that conceit to rest. Our full testimony is to be found only in our bivalent actions and words!

I find one of the opening quotes of ch. 5 intriguing, though I’m still holding it at arm’s length and trying to decide how to understand it.

The rejectability of the gospel is ironically what prevents it from becoming mere propaganda. Consequently, the Good News cannot be fully understood as good news unless the gospel is offered in noncoercive ways.

-Brad J. Kallenberg

The last sentence there … yeah. That makes sense. Can anybody else help illuminate that first sentence - about mere propaganda? So if in math class today students are taught to reject wrong sums - because there is a right answer they need to arrive at, it appears we have ‘non-rejectability’ in math class. So is math mere propaganda then?

This particular chapter is also a great segway from your Lakota video, @Kendel.

Another good quote; this one from Penner (p. 144).

When emphasis is on objectivity, I should not just attempt to lead a thirsty horse to water; I should drag it. And once I have done so, I should do all I can to make them drink–whether they think they want my water or not!

I think Penner said elsewhere (maybe in a prior chapter), that in a modernist world of alleged objectivity, we attempt to possess truths. In a subjective (and apostolic) world, the truth possesses us.

What keeps coming to my mind in this context is also the importance of constantly evaluating our lived out hermeneutic both in our individual lives and in the life of the church. At the risk of sounding like I endorse t-shirt slogan quality theology or the “church growth movement,” I’ll say anyway, we have GOT to evaluate based on the views of those receiving our witness, what our witness actually seems to convey.

All too often, I hear christians excuse insensitive, loveless, damaging behavior as “being different from the world” or “being misunderstood by the world.” (That faceless unbeliever again) When what “the world” stands in horror, seeing ….well all the awful stuff we see in the news for example, that is coming out of churches. Or they’re seeing the hypocrisy of their christian neighbors, Or any other thing that just alienates, rather than the kind of witness that might lead them to say, “Yeah, they’ve got some odd believes. That’s true. But when my life was falling apart, they were there to help me get through it. And they really show that they care about me and my family. They’re actually really good friends.”