Oh yeah! - It is quite a distinction to be sure, whether I am in a given moment in the role of a found sheep, a lost sheep, or even a swine! What doesn’t seem kosher, though, is to permanently assign groups of people one of those labels - or even one person that you happen to not like. They might be behaving like a swine and need to be called out. Or then again, depending on my own attitude or the spirit by which I’m presuming to call somebody else out - maybe it’s me being the swine! As I said … fluid categories, which doesn’t make them any less real.

Sheep, lost or found, can be pretty insensitive.

That is true! The prophets, the apostles, … Christ himself - none of them are known for giving us any very flattering looks at ourselves.

I already mentioned one synonym: gullible.

Would “casting seeds onto rocky ground” be a better metaphor/parable?

It’s not alliterative. ; - )

Here is a chapter 4 quote for the day, in case we haven’t had one recently.

p. 127

Thus, truth for the Christian is a task, and the task is not to know the truth intellectually but to become the truth.

Okay - and I just can’t leave my own post above well enough alone. I’ve got to cut loose with more reaction here.

Is it just me, or has anybody else experienced something like this? What I mean is this. I think I know (or like to imagine I do) exactly what Penner means by “being the truth.” Because I regularly experience this in my own thoughts, words, and deeds towards other people (or all too often, miserably fail of the same). There are times when I think (or - Lord have mercy - actually voice) something to another person that immediately leaves me (not to mention, them) feeling disturbed in spirit. As in - I realize even after I’ve thought or said it, how ugly - or perhaps in some subtle or not-so-subtle way: how mean the expression was. I immediately have the visceral reaction of wishing that I had not spoken as I did. Which I think is my conscience telling me that I was not living truth toward that person. It has nothing to do with the actual veracity of what I propositionally uttered (though it might literally be that), but could have been very true things spoken with an untrue spirit.

Of much more delight is the opposite feeling I have after an aptly spoken (and well-received) word - or maybe it was just me listening and not saying anything - after which I feel that pleasurable feeling of shalom or rightness with my neighbor - with the world. And again, the actual content of what I may have uttered may not necessarily have been helpful or even very intelligent - and yet - my almost unmistakable feeling is that both my neighbor and myself were edified for the exchange, and that is what I imagine as my neighbor and myself as being living truth towards each other.

I.e., become Christlike (I have a ways to go).

Reminiscent also of the Latin anagram I like so much that answers Pilate’s question (and Discourse noted I had already posted here… a month ago back in reply 112, I discovered ; - ):

Quid est veritas? “What is truth?”

Est vir qui adest: “It is the man who is here.”

Note – becoming the truth includes the whole person, including the intellect. Remember about being childlike: they ask “Why?” a lot!

One:

Language Games

For days I’ve hemmed and hawed to myself about commenting on “Language Games,” because other people here are better at pulling out riches and just putting them in front of us. I often feel like I approach things sideways, and this is another example.

“Language Games” is an important concept in Postmodernism and has lead to a number of conclusions related to the im/possibility of actual communication and understanding between people, languages, cultures and times. Sound familiar? Much of the related thought is hardly encouraging for those of us who seek to engage in truth-telling or truthful speech with others. It certainly wasn’t affirming after having worked very hard to do precisely that in two different cultures myself. So, I found Penner’s discussion of Language Games hopeful and useful as well.

On pp. 117-118 he identifies the problem of Language Games (and I have abridged for brevity; bolding is mine):

…[T]he languages we speak and the truths we tell, and even the insights we have, are all set within the contexts of the social and cultural practices of our various and sundry communities, which form perspectives through which we perceive the world and apprehend truths. But it also means that when we try to theorize about truth (that is, when we try to describe what truth is) using concepts like “correspondence”–so that we can somehow get at it from behind, underneath, or outside the concrete practices in which we make, speak, and act–we will not have much luck. There is no further illumination to be had in that direction. We keep hitting dead ends.

This is a widely held postmodern understanding of the problem of language (which is defined very broadly), that we can never, really get to the bottom of understanding what another mind, much less one from another culture is attempting to communicate. (And yet we continue to try…endlessly.)

Penner proposes a concept of language and communication different from what postmodern theorists are willing to concede: “lateral universals” or “transversals.”

…[Y]et whenever I think or express myself in language, my thoughts or words are incipiently universal insofar as they may be understood by others. The categories and rules of language are inherently public, not private, shared at very least by others who inhabit the same language games and engage in the practices and behaviors I do. Since we humans inhabit the world under fundamentally similar conditions, with similar bodies, needs, desires, and practices, we possess the potential to understand each other.

…We are not trapped in our language games, but the languages we speak-their terms of reference, their truths, their sense, and so on-are always potentially understandable by those outside of them (although, not necessarily straightaway and definitely not by the sheer force of our rational capabilities). To understand me, someone will have to spend time mastering the language game I speak, as well as carefully attending to my life. (pp. 119 and 120)

It is important to underscore that in my description here, language and culture create the possibility for our (finite, fallible, and contingent) experience of truth rather than act as a barrier to truth. …The gospel truths we proclaim as witnesses are, in a manner of speaking, the gospel-as-we-have-encountered–it within the community and practices of those who confess Jesus as their Lord. And the specific truths we witness reflect how we have understood the gospel from within our particular cultural moment. (p. 120)

This has been my experience, living in different cultures, wielding a language, of which I had worked very hard to achieve some basic mastery. Often there was a great deal of hammering out of meaning and seeking the right expression, even wrangling over word order and case. At times, what seemed like endless clarification. However, as a foreigner to that language and those cultures, I also had “outsider insights” to things that a native speaker never notices. And I enjoyed reciprocal edification as well. And real, meaningful communication occurred.

Working to think in these ways and master a grasp of someone else’s language and concepts is often frustrating and exhausting. But it’s the real deal. Recognizing that we are approaching people who are not empty receptacles, waiting to receive whatever it is we deem necessary to place in them is humbling. And respectful of their humanity and experience.

Engaging with anyone in this way, however, is always dangerous. We open ourselves up to some perspective we had never considered, which might actually be edifying. Penner points out in different words, that everything must be carefully considered. But we must realize that that careful consideration is happening on both sides of the conversation.

As Christians involved in this kind of (sometimes gospel-related) dialogue, we can seek to be edified as well. Specifically:

- in a better understanding of actual, living humans with whom we are in relationship, rather than a theoretical “person” to whom we try to apply a certain formula; and

- in a better understanding of of how we should be seeking a better/fuller/closer relationship with God in Jesus as we look more closely at the gospel in our own lives.

I understand that the idea of dialog and mutual edification, particularly in matters relating to God, can seem unnerving. Sometimes it really is. While I really believe the gospel and “standard Christian doctrines”, which include an external, transcendent God, I understand that there are people who simply don’t and have reasons that make sense. I’m not convinced that there’s a right word that’s going to come from me to change their minds, and if it comes out of my mouth, it’s the work of the Holy Spirit. Whether that happens or not, I will work for mutual understanding and respect, which I find much more productive than alienation and wall-building.

Two:

Yes, there’s more. I wrote to Myron B. Penner (as well as Myron A. Penner–oops) and I heard back (from both)!

Myron A. Penner is a philosophy prof in BC Canada. If you write to him by accident, he’s real gracious about the error.

Myron B. Penner is the author of our book and rector at St. John’s Anglican church in Edmonton, Canada.

I thanked him for the book and the work that went into it, and asked for a bibliography, if he had one handy.

From his reply:

Thank you very much for reaching out to me. It is greatly encouraging to hear that TEA has been edifying for you and you online group. That is, after all, it’s aspiration! I appreciate your taking the time to contact me about it.

[Regarding the bibliography] I do not have one ready-to-hand. I did see on the Discussion Board you created some references to some of relevant lit. You may also want to know that Philosophia Christi published a brief series of exchanges between Bradley Seaman and I on TEA (I can look up which issues for you, if you like - l’ll attach copies). My pieces are titled “Alethic (Quasi-)Realism: Idolatry, Truth, and the Limits of Language,” and “Referring to Words: Idolatry, Truth, and the Possibility of Naming God.” (It probably isn’t fair to attach Brad Seaman’s work without asking him first.)

Thank you again for your thoughtful engagement with TEA and for letting me know about it. Please feel free to be in touch.

And if you read this far, you get a great big ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

He lives up to the t-shirt. Caught about 90 seconds, which included at least 2 fast-talking mischaracterizations of “the other side.” Which I hate. And how does one work through the spew with the spewer?

Yes, he clearly has read (or at least taken content of some sort) a lot and knows a lot. But if the stuff one knows is off and relies on mischaracterizing “the other side,” isn’t it like having a PhD in alchemy or homeopathy?

Honestly, he should take the time away from body sculpting with bar bells, and use it for a thoughtful, deep reading of Penner’s book, and referred to texts. But you don’t get to be rowdy about these things.

It’s certainly me. All too often, Merv.

I think in general, I have proven to be more edifying in my communications, when my mouth is shut. At least in writing, as you have mentioned elsewhen, there is time and space to think it through, test the tone out, read it over, and reconsider, before licking the envelope and placing the stamp, or pressing “send”. And still I fail all too often even with written media.

Did’jer family watch you?

I’d have hated to have been asked to interpret for the Deaf.

Not important, but … I missed the “mischaracterizations”.

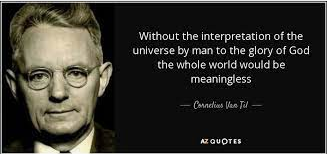

Van Til is tough stuff for some of us to wade through, but Durbin sums him up pretty quick with a quote:

Durbin’s “Read [Greg] Bahnsen!” sums up what Durbin has to say about Bahnsen.

Caveat: Neither Bahnsen nor Durbin are for the timid.

Not quite, more like “a ‘Bad Boy’ goes straight” and “a two-pack-a-day Smoker quits smoking”…eventually. Not that anyone asked nor that I am “a fan of the man”; but don’t let anyone accuse me of not letting him speak for himself: Rooted Testimonies: Jeff Durbin’s Story.

[Note to “Fact checkers”: “Bad Boy” and “two-pack-a-day Smoker” are my choice of metaphors."]

An observation on 1 Peter 3:15, which Reformed Calvinists like to call "the Charter verse of Christian apologetics":

-

κύριον δὲ τὸν Χριστὸν ἁγιάσατε ἐν ταῖς καρδίαις ὑμῶν ἕτοιμοι ἀεὶ πρὸς ἀπολογίαν παντὶ τῷ αἰτοῦντι ὑμᾶς λόγον περὶ τῆς ἐν ὑμῖν ἐλπίδος (3:16) ἀλλὰ μετὰ πραΰτητος καὶ φόβου

-

but sanctify Christ as Lord in your hearts, always being ready to make a defense to everyone who asks you to give an account for the hope that is in you, but with gentleness and respect;

-

Who added that "to everyone who asks you to give an account for the hope that is in you, but with gentleness and respect" ?

Curious to see what a “tamer” Reformed Calvinist might have to say about Penner’s book, I looked around and came across pastor, professor, and author Timothy Paul Jones’ paper presented at the 2021 Evangelical Theological Society Annual Meeting, in Fort Worth, Texas.

Title: The End of Apologetics?

“Something Divine Mingled Among Them”: Care for the Parentless and the Poor as Ecclesial Apologetic in the Second Century.

In a section headlined “The Exit Door You’re Looking For May Be Behind You”, Jones wrote:

- In the second century in particular, a multiplicity of Christian writers—including Aristides of Athens, Athenagoras of Athens, Justin, and the author of Epistle to Diognetus, to name a few — grounded key portions of their arguments in the ethics of the Christian community. This pattern stood in clear continuity with the apologetic described in the first three chapters of 1 Peter, where the moral life of the church is the primary defense of the Christian faith (1 Peter 2:12–3:7, 16).

- For these second-century apologists, the moral habits of the church provided a common ground on which to structure their arguments. This common ground was not “common” in the sense that Christians and non-Christians both practiced these ethics or even in the sense that both aspired to practice these ethics. Christian ethics provided a common ground in the sense that even non-Christians could not deny that this was how Christians lived. This argument did not require agreement on the terms of a rational common ground; it required the common recognition of a particular pattern of life.

- For the Christians who articulated this apologetic, the life of the church was not merely a context for the practice of Christian faith but a primary evidence for the truth of Christian faith. To put it another way, their apologetic was, at least in part, an ecclesial apologetic —an argument that contended for the truth that the church confesses on the basis of the life that the church lives. The moral habits that sustained ecclesial apologetics in the ancient church encompassed a wide range of countercultural practices, including sexual continence, truthfulness, justice, contentment, kindness, humility, and honor for parents. The focus of this research, however, is on a single strand within these ethics that was particularly prominent among the church’s moral habits—sacrificial care for orphans and for the poor. A close examination of this moral habit in the second century reveals an ecclesial apologetic that was grounded in the Spirit-empowered work of the people of God on behalf of the vulnerable.

Terry, slowly the question I should have asked weeks ago is percolating to the surface of my mind. You seem to have a background with some aspects of the World of Apologetics, and you know what’s going on there, what the issues and schools of thought are, and I think there, behind those not-so-off-the-cuff posts (just look at the formatting alone!), there’s more than what shows up in the thread. So, what’s your background with apologetics? I know you’ve expressed exercising restraint regarding what and how and how much you post in this thread. But I”m asking: What are your thoughts regarding Penner’s criticisms of modern apologetics, his description of postmodern witness, and finally Penner’s recommendations for how Christians ought to live out their faith? Oh, yeah, and whatever you think I forgot to ask, please do that and answer, too.

Thanks!

Kendel

Along the same lines mentioned a while back…

There’s a Wikipedia article on the book:

The Rise of Christianity

The Rise of Christianity (subtitled either A Sociologist Reconsiders History or How the Obscure, Marginal Jesus Movement Became the Dominant Religious Force in the Western World in a Few Centuries, depending on the edition), is a book by the sociologist Rodney Stark, which examines the rise of Christianity, from a small movement in Galilee and Judea at the time of Jesus to the majority religion of the Roman Empire a few centuries later. Stark argues that contrary to popular belief, Christianity …

Van Til is tough stuff for some of us to wade through, but Durbin sums him up pretty quick with a quote:

Wow; I’ve never read VanTil, though I thought his writing was a different bent. Did he think God depended on man to give meaning? Thanks.

Did he think God depended on man to give meaning?

Absolutely, unequivocally not.

- My problem with him is that his writings are almost impossible for me to read through. Greg Bahnsen made him “intelligible” and slightly more “readable”, along with short quotes from Van Til’s writings. Sampling: Cornelius Van Til Quotes

- Warning: There’s no getting through either without a complete comfort with “Sola Scriptura”: Both have a “high view” of Scripture equal only to Islam’s view of the Qur’an or the Latter-Day-Saint’s view of “The Book of Mormon”.

Thanks. I had the impression he believed a bit in the necessity of belief to fully understand a faith.–presuppositional apologetics. I’ll look a bit through that