That’s an overstatement, Richard

In my previous post I outlined the way in which individual pericopes about Jesus were selected and juxtaposed by the Gospel authors. Their primary intention was to craft the story of Jesus to address the situation of their day. In this endeavour, they were interpreting the story long before our attempts to do the same. Before this, Jesus himself probably used the same elements of his teaching to adapt to his context in different ways. So aspects of Jesus’ teaching were most likely being interpreted in different ways by Jesus himself.

There is a further aspect of interpretation involved in this transmission. When the people of Judah rebelled against their Babylonian overlords, they were defeated and thousands were taken away in exile. After a few generations, and the conquering of the Babylonians by the Persians, the Judahites were permitted to return to Judea and rebuild their temple in Jerusalem and the city walls.

However, a very significant change had occurred. Over many centuries, the common language of Mesopotamia had become Aramaic. Aramaic had humble beginnings as the language of the ancient kingdom of Aram and the Aramaic tribes. The Assyrians had conquered the Aramaeans militarily centuries before, but the Aramaeans conquered the Assyrians culturally and linguistically. Aramaic became the common language of Mesopotamia including the Assyrians, Babylonians and Persians. But how did this express itself in writing? Cuneiform expressed ideas in pictorial ways – with stick figures representing people and things. This was similar to Egyptian hieroglyphics, but not nearly as colorful as Egyptian hieroglyphics. However, Aramaic had an alphabetical writing script in which letters expressed the sounds of the spoken language. Scribes had the choice of having to learn more than 600 Cuneiform symbols, or a mere 22 letters of the Aramaic alphabet. It was a no-brainer!

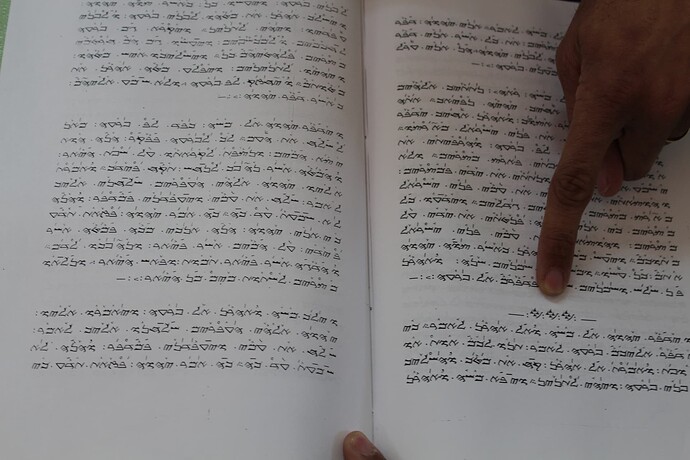

When the Judahites returned from their exile in Babylon, they came back speaking Aramaic and writing Aramaic with the Aramaic alphabet. Hebrew, which was a Canaanite language, became the holy language of the synagogue and the Jerusalem temple. Fascinatingly, the returning Judahites wrote the Hebrew language in the square writing script of the Aramaic language, and they still do to this day.

I will try to include a graphic of the original script in which Hebrew was written.

(I think I got this right. I can’t actually read paleo-Hebrew and I’m not in a hurry to learn it.)

The point of this historical excursion is to explain why most scholars believe Jesus preached and taught in the Aramaic language. This means there was another level of interpretation involved. As far as we know, the original manuscripts of the Gospels were written in Greek, (although some have argued for an Aramaic original of the Gospel of Matthew). At points in the Greek Gospels, small amounts of Aramaic start to show through.

Summing up then, there is a degree of interpretation taking place right from the start. The translation from Aramaic to Greek, the selection or omission of pericopes by the Gospel authors, and the effect of different juxtapositions by those authors. Finally, we come to translation into modern languages, including English. The most famous of those translations into English is probably the King James version of the Bible, which translated the text into early modern English. There is a problem with the KJV. As manuscripts were copied, errors in copying naturally crept in, so later manuscripts have more errors. Current translations into English go back to earlier manuscripts with less errors than the KJV. They also have the benefit of better knowledge of the vocabulary and syntax of the ancient Biblical languages than translators had in 1611.

So, next time someone declares that Scripture is the sole and absolute authority, and waves a copy of the KJV in the air – well, there is a lot to think about.

Those two are not strictly linked: if scripture is God’s words, then certainly it has authority, but it does not have to be dictated or prescribed to have authority.

Scripture is the ultimate authority we have because there is nothing else with the imprimatur of being inspired. That doesn’t undermine God’s authority because it is His authority.

Of course: if the scripture isn’t authoritative, then it isn’t worth discussing since then anyone can claim that God told them whatever they want someone to believe.

That makes it all subjective, and Charles Manson or Sun Myung Moon or Kim Il Sung are just as valid teachers as anyone else. The logical result of your position is that God’s character becomes a meaningless concept – it’s the equivalent of allowing scientists to just make up their own data and call it research.

No, you are – you are making God cruel by calling natural consequences “punishment”.

Humans were made for a relationship with God. Without God we are like a steam locomotive trying to travel through a marsh instead of on the rails of the track the locomotive was built for. What you call “punishment” is the results of trying to define where we should go by ourselves – i.e. declaring ourselves to be our own god.

That accounts for a large portion of all consequences. The alternative is to see humans as omniscient.

I’m not the one calling everything bad that happens “punishment”.

You think there is no doctrine of the Fall before Paul?

All Paul did was recognize and expound on what is found all through the prophets and in Jesus’ own teachings.

Interesting stuff, @gregoreite . It also surprises me to learn that other than a few fragments here and there, the Old Testament manuscripts that are relatively intact are dated from 900-1000 AD (roughly), though the Dead Sea Scrolls have quite a few extensive fragments, and most of Isaiah. And that the Hebrew of the Masoretic Text uses the Aramaic alphabet, so is actually a sort of translation itself. Linguistics gets as messy as biology, it seems.

Go on then, show me. Not that a prophet claimed that all were sinful, but that that sin came from Adam.

Also that Jesus specified that sins came from Adam.

Show me.

RIchard

I’m not going to play to your prejudices and denial of scripture by playing your game here. It does not require Paul to have the doctrine of the Fall; it is a constant thread through scripture. Paul only summarized what is in Genesis and onward.

It is not about what I see in Scripture it is aboug you backing up your claim. If you cannot or will not, why should I believe you?

Judaism has no doctrine of Original Sin so if you are going to claim OT backing you are going to have toshow ir. Otherwise I might resort to your own mantra o

“Making things up”

Put up or shut up.

Richard

Now a third, largish post.

First of all, Natural Theology has its source in Nature, not the Bible. St Paul pointed us to Nature, as an additional source for the revelation of God’s power and God’s nature:

For since the creation of the world, God’s invisible qualities–his eternal power and divine nature–have been clearly seen, being understood from what has been made, so that people are without excuse. (Romans 1:20 NIV)

Hugh of St Victor put it very clearly, if God is the Creator, then “Nature is a book written by the finger of God.”

Natural Theology turns to what was known as “Natural Philosophy”. We used to call science “Natural Philosophy”. Something of those origins is still found when someone earns a PhD in science. PhD is an abbreviation for “Doctor of Philosophy (of Nature)”.

What contribution does Natural Theology make to our salvation. Well, if you think that “salvation” is only about some abstract situation in another worldly realm , you probably don’t understand what salvation means. Salvation happens in the here and now, as well as in the world to come. Jesus’ ministry of preaching, teaching and healing, took place in the here and now, and people were healed as part of that ministry, in the here and now. In other words, whatever else it might be, salvation is pastoral.

Let me suggest a few places where Natural Theology might contribute to our understanding of, and experience of, salvation - the least controversial first.

From just before the time of Jesus and throughout the Christian era, the notion of the “End” is found. The study of notions of the “End” is known as “eschatology”, from the Greek word “eschaton” meaning “end”. In both the Biblical literature and modern English, the word “end” has a dual meaning. It can mean both the end in a chronological sequence and the goal to which something moves. “The football match came to an end, but to what end did we play in the football match.”

In terms of Biblical terminology, the end initially meant the moment when God called time; the resurrection of the dead and the last judgement. Then along came Jesus who created a complication. In Jesus’ resurrection he became the firstborn from the dead, but only the beginning of the end, as St Paul portrayed it in 1 Corinthians 15. The resurrection of others would follow later. Now then, what happens when a Christian dies? Does he or she immediately enter paradise, or sleep until the second coming? (Now all you 19th Century Fundamentalists who think you know the answer, just hold back for a moment.) I often found people arguing about Jesus’ words to the thief on the cross: “I say to you today you will be with me in paradise”. It all depended on where you put the comma. “I say to you, today you will be with me in paradise”. Or, “I say to you today, you will be with me in paradise”. By the way, there is no comma in the earliest Greek manuscripts.

What does science (Natural Philosophy) say about the end of time? If you lived at the end of the 19th Century, when the science of Sir Isaac Newton prevailed, you would understand that even if the universe dissolved into nothingness, time would still march on. But in fact, science marched on. First, the Rev John Michell proposed the existence of “dark stars” whose gravitational pull was so strong that even light could not leave it. “Dark stars” became known as “Black Holes”. Einstein proposed that time was a fourth dimension of the physical universe, he called it “space-time”. Under certain conditions, such as in a Black Hole, time would stop. Now right at the centre of our galaxy there is a super-massive Black Hole in which time stops. The Black Hole is physically located adjacent to locations where time does not stop, so the end of time can exist alongside the places where time has not ended. So what does that mean for the argument over where to place a comma in the sentence, “I say to you today you will be with me in paradise.” Think it through for yourselves!

Now let me go to something that will be a little more controversial among North American Fundamentalists – homosexuality. But before we discuss the issue theoretically, let us approach it pastorally. A common experience amongst Christian people who discover at puberty that they have a homosexual orientation is to regard themselves with horror, especially if they have grown up in a Fundamentalist family which regards such an orientation as an abomination. Such a person, caught in a contradiction between who they are and who they think they should be, often enter into programs that will supposedly “cure” them of their sexual orientation. Some of these programs can be horrific. After the program, the person might believe that they have been “cured” because they want to believe it. But the same sexual orientation remains. Unfortunately, some people in this predicament will conclude that they are so evil that nothing or no one can help them, and they commit suicide.

What if we turned to Natural Theology based on Natural Philosophy, otherwise known as science? There we would learn that sexual orientation is determined by a part of the brain known as the anterior hypothalamus, and it cannot be changed. That might stop us laying impossible expectations on people whose road through life is already very difficult. The question is, “Does God speak to us through Nature, as the Creator of Nature, and should we not listen to that as much as we listen to the Bible, if we are truly pastorally concerned?” I expect a deluge of different views.

It has been interesting to read about your thinking. I expect that you will continue with additional texts. Before you continue, I like to give a comment on your rationale about Natural Theology.

I do believe that we can learn about God and His thinking by studying nature. However, there is a caveat. Nature includes a wide variety of life forms and behaviours. That we can observe a particular kind of behaviour in nature does not in any ways tell what is good and what is bad. Science does not either tell what is good and what is bad.

I could list many behaviours that may be even fairly common in nature but which may be considered ‘bad’ by at least some human societies.

For example, infanticide is fairly common in nature and can be considered rational behaviour. Sometimes the reason is too little food (it is ‘wise’ for the mother to eat her offspring if she cannot provide enough of food for the youngs to grow and survive). Sometimes the reason is intraspecific competition (it is prudent to increase the survival prospects of own offspring by getting rid of the offspring of others; killing and eating the competing offspring does also fill the stomach). Sometimes the reason is an attempt of a male to get more offspring; for example, a lactating female bear may not be receptive but if a new dominant male kills her offspring, she may mate with the male much sooner than otherwise. The counterstrategy of females is to copulate with all strong males around with the hope that the male will not kill her offspring if he thinks he may have sired the cubs.

Completely rational behaviour by animals in nature but ethically unacceptable in human societies, at least in those societies that have inherited the ethical code from Christian teaching.

Some societies may accept infanticide in special circumstances. For example, abortion may be accepted if the fetus was sired in a rape. In some pre-Christian societies, newborns, especially girls, were sometimes left to die in nature or elsewhere. Is that kind of behaviour acceptable or not depends on the ethical code and values of the society. Watching nature does not reveal what is the ‘correct’ ethical code.

So, does that mean God is not reflected in Nature? Or does it mean that Christian (any) ethics can be deduced from Naure?

Is this anpthe case of All or nothing?

Are theology or ethics drived soley from one source? Perha[s the Christian view of ethics is not the Universal (uman) one> Does that make either or both valid?

Perhaps Romans 1 is a temper against Christian (Scriptural) dogmatism. That would agree with Ecclesisates whereby a single source or focus is viewed as folly or meaningless.

I am sure that those who consider Scripture as either paramount or sola would obviously disagree.

Richard

PS

Does Ecclesisastes teach against sola scrptura? it would be an enormous paradox if it does.

The acts (thinking) of God is reflected in Nature but everything that happens in Nature does not reveal the will of God. It is the same as with humans: I believe God created humans but everything that humans do does not reflect the will of God.

Studying Nature to learn about the thinking of God is a challenge that demands wisdom and patience. It is the same as trying to learn about the will of God by studying humanity. Seeing and understanding the created patterns within the wild weave formed by the acts of humans with free will may be a challenging task. Maybe a too laborious task for those who want simple answers, here and now.

Does Ecclesisastes teach against sola scrptura?

Does Ecclesiastes teach against sola scrptura?

ChatGPT said:

ChatGPT

Ecclesiastes does not directly address the doctrine of sola scriptura (the teaching that Scripture alone is the ultimate authority for faith and practice) because sola scriptura is a theological principle that emerged during the Protestant Reformation, long after Ecclesiastes was written. However, some passages in Ecclesiastes can be interpreted in ways that challenge or nuance certain approaches to biblical authority and wisdom.

Key Passages in Ecclesiastes

Ecclesiastes 12:12-14:

"Of making many books there is no end, and much study wearies the body. Now all has been heard; here is the conclusion of the matter: Fear God and keep his commandments, for this is the duty of all mankind. For God will bring every deed into judgment, including every hidden thing, whether it is good or evil."

This passage emphasizes the ultimate authority of God's commandments and judgment. It critiques the endless production of human wisdom and writings, which could be seen as a call to prioritize divine revelation over human speculation. However, it doesn't explicitly limit divine revelation to Scripture alone.

Ecclesiastes 1:9-10:

"What has been will be again, what has been done will be done again; there is nothing new under the sun."

This could suggest skepticism about human innovation in wisdom, implying that divine wisdom, as revealed through Scripture or other means, is timeless and superior.

Ecclesiastes 3:11:

"He has made everything beautiful in its time. He has also set eternity in the human heart; yet no one can fathom what God has done from beginning to end."

This verse underscores the limits of human understanding and could be read as pointing to the necessity of divine revelation for knowledge about God and ultimate truth.

Theological Reflections

Ecclesiastes repeatedly emphasizes the limitations of human wisdom and the necessity of revering God. While this aligns with the Protestant emphasis on the sufficiency of divine revelation, Ecclesiastes does not explicitly confine that revelation to written Scripture. In fact, the text reflects a broader view of God’s wisdom that includes natural revelation (e.g., observing creation) and experiential insights about life.

Does Ecclesiastes Oppose Sola Scriptura?

Not directly. Ecclesiastes critiques reliance on human wisdom and underscores the necessity of divine guidance, but it does not restrict this guidance to the written Word of God. The doctrine of sola scriptura would require broader biblical and theological arguments beyond Ecclesiastes, drawing on passages that emphasize the inspiration and sufficiency of Scripture, such as 2 Timothy 3:16-17 or Psalm 19:7-9.

If you’re exploring whether Ecclesiastes might suggest a broader source of divine revelation than Scripture alone, that’s a theological debate where Ecclesiastes could be seen as one piece of the larger conversation. It neither explicitly supports nor refutes sola scriptura.

If you’re exploring whether Ecclesiastes might suggest a broader source of divine revelation than Scripture alone, that’s a theological debate where Ecclesiastes could be seen as one piece of the larger conversation. It neither explicitly supports nor refutes sola scriptura.

Ecclessistes basically claims that a single focussed apporach, be it wisdom, pleasure, or study, is meaningless the upshot being a broader more catholic (smallc) apprach to likfe which would seem to rule out relying on a single source of Scrioture.

That may be a simplistic understnading and there is much more to be gleanes=d, but i would claim that as such it is trying to deter people from relying on one thing, anything, except God Himself.

Of course, if you beleive Scripture is Gd Himself , as in God in written form, you can probalby argue against this and justify sola scriptura on the grounds that it is God talking and that overides any other source.

But, as I refute that Scriture is God;s words I also refute sols scriotura… Scirture is sacred, even sacrisanct but it is not God in written for on a par with Christ, who is God in human form. (Making a quadrilogy)

Richard

Ecclessistes basically claims that a single focussed apporach, be it wisdom, pleasure, or study, is meaningless the upshot being a broader more catholic (smallc) apprach to likfe which would seem to rule out relying on a single source of Scrioture.

It seems we have a different understanding about both Sola Scriptura and Ecclesiastes.

You draw a caricature (strawman) of Sola Scriptura and then mock it. Claiming that Sola Scriptura means that we make the biblical scriptures equal to God is unfounded.

Your interpretation about the general message of Ecclesiastes is one-sided. After reading your comment I had to read Ecclesiastes once again to see if your interpretation is true. There are passages recommending avoidance of the extremes (especially 7:16-18) but otherwise, there seems to be a general tendency to recommend wisdom and telling that the pleasures of this life are not worth much - you can enjoy of them but remember that we will be one day judged by God.

The overall tone is that of an old man that thinks about the life of humans with somewhat depressed thoughts. If you take that into account, Ecclesiastes rather recommends obeying what God has said rather than speaking against it or the judgement that will come.

Edit:

I do not claim or think that God has dictated what is written in Ecclesiastes. It is the writing of a human that has received wisdom and guidance from God during his life and in the writing. Allthough I consider it a writing of a human, it is part of the biblical scriptures that the early believers recognized as authoritative and were included within the canon. If interpreted in a wise and justifiable way the biblical scriptures have more authority than the opinions of a church leader because the canon represents the teachings of the early believers (catholic church with small c). That is what Sola Scriptura means.

he canon represents the teachings of the early believers

Where, even in Scripture does it say that the teachings of the early beleivers is superior or better that now? Logic would dictate the reverse. The more experience: the better the understanding… And, seeing as our view of Scriture is automatically focussed by our modern undestandings…

Your interpretation about the general message of Ecclesiastes is one-sided

I only claimed it as simplistic. If you want a detailed analysis I am sure we could discuss it for days on end.

The end of the matter; all has been heard. Fear God and keep his commandments, for this is the whole duty of man.

I wonder if that sums up your views of life and faith.

I would be so bold as to claim that it is also one sided, but not the side I was looking for.

You draw a caricature (strawman) of Sola Scriptura and then mock it. Claiming that Sola Scriptura means that we make the biblical scriptures equal to God is unfounded.

It is, I will admt the sharp end of the wedge, but there is an underlying beleig=f that God did more than influence Scripture making it beyond argument.

Furthermore, by claiming ro take Scripture above all other you are opeing yourself up to comlaints about freedom, Male chauvenism, Might is right, and the notion that we must all worship God or else (some of which can be seen running rife here).

Richard

Where, even in Scripture does it say that the teachings of the early beleivers is superior or better that now? Logic would dictate the reverse. The more experience: the better the understanding…

Classical Christian teaching is built on the teachings of Jesus and his apostles. The closer the teaching is to the original apostolic teaching, the more we can be assured that we have not stepped off the path set by Jesus and his apostles.

The apostles were bringing the teachings to various parts of the known world. Those hearing and believing told the message to others and so the faith spread. Those being close to the beginning of the chain probably had a better knowledge of the original apostolic teaching. We assume that the decisions of the first ecumenical councils reflected this teaching - the canon of scriptures that had been widely recognized as authoritative and read in local churches, the Nicene creed.

During the following centuries and millenia, more doctrines were added and the way how previous teachings were understood and applied changed. Many new doctrines were controversial in the sense that they were not universally accepted and seemed to be partly in conflict with the original apostolic teaching as reflected in the biblical scriptures. It is justifiable to ask if we can anymore trust that the teachings that had changed during the centuries represented the original apostolic teaching. Reformation is one sign that many judged that this slide off the original path had gone too far.

These are the reasons why we can trust more the teachings of the early believers, from the time of the undivided catholic church or earlier, than the contradictory messages and doctrines that are now proclaimed in various denominations, including the old churches.

If you want something else than the original, there is a freedom to proclaim something else. It can be questioned whether such teachings are anymore ‘apostolic’ or ‘classical Christianity’ in the sense that it is what Jesus and his apostles were teaching.

Those being close to the beginning of the chain probably had a better knowledge of the original apostolic teaching.

There is one problem here.

The apostles were all Jews, including Paul. Jesus, Himself claimed to be teaching the Jews. Therefore everythnig is based on Jewish thought and understanding. Not only that but you also have to facttor in the world view of the apostles.

In Romans 14 Paul makes an allowance for those who do not know or have to abide by the Decalogue (Some hold a day to be special etc.) However most of his teaching is aimed at ether Jews or converted gentiles. He does not address non beleivers in his letters. The only interaction with non beleivers is in the book of Acts and , even there, it is very limited.

I am not a Jew. I may have some Jewish heritage, on my mother’s side(surnam Abrams) but that does not make me bound by anything Jewish. Jews have a view of God, reflected in Paul’s teaching, whereby God controls everything. He hardens hearts, He targets specific people both for favour and for attack. It is a world view that most chrstians do no support. Paul talks abut slavery and being a slave to either sin or God. I am neither and I refuse to be compeleed into thinking otherwise by a “view” of Scripture.

There is no choice in Judaism, There is no free will in Judaism. Are you telling me that i must not beleive in free will?

Without Free will God becomses maniplative and dictatorial, which aligns with Judaism.

Insisting on being a Chistian is dictatorial.

Insisitng that anyone who refuses (or does not accept) forgiveness is dictatorial.

Is God dictaorial!

If the answer is Yes then He is not worthy of my worship.It makes HIm no better than any dictator who claims peace under his rule and leadership.

So you have to decide. Is the message of Scripture one that reflects a loving forgiving God?

Or one tha reflects a domineering, dictatorial, manipulating God who only “saves” those who worship Him, and then only if they are Christian!

iI is very easy to get the second verrsion from the details of Scripture, which is where the phrase

“The Devil is in the details”

comes from.

As soon as you start delving deep into Scripture you come unstuck. Sola Scriptura fails.

The Christian message is (should be) that God forgives sins. All sins. Any sins, without any caveat whatsoever.

Salvation is not about actions (sins) it is about thoughts and intents. God can forgive all sins and leave open the door for judging the intentions.

The warning for this is that if someone declares Christianity for the wrong intent, or dismisses humanity on the grounds of Christianity and therefore disregards them…

They are risking the judgement that they joined Christianity to avoid.

Christ’s teaching underlies the necessity for the right frame of mind and the right intentions. If you think iy then it is the same as doing it. If your intent is not righteous then the actions will not be righteous. If you only help others out of some sense of obedience then you have it wrong. If you only govern your life and actions to obey what you see in Scripture then you have it wrong. Sola scriptura fails.

Richard

There is one problem here.

The apostles were all Jews, including Paul. Jesus, Himself claimed to be teaching the Jews. Therefore everythnig is based on Jewish thought and understanding.

Yes, the original teaching was firmly rooted in the Hebrew knowledge of God as understood (interpreted) from the Hebrew Bible. It can be claimed that when the leadership shifted to gentiles and the bishops and other church leaders were raised in the Greek-Roman cultural heritage, without deep knowledge of Hebrew thinking and scriptures, the slide off the original path started.

At first the slide was perhaps just accomodation to the new context and adding new insights from a different viewpoint, relatively slight and probably necessary changes. During the following centuries, there happened more crucial changes. Ideas and beliefs of gentile cultures, especially the Greek-Roman world, were incorporated to the teaching of the church. Inclusion of philosophical ideas may have been partly what was also found in the Jewish world, like the incorporation of the Platonic philosophy by the Jews of Alexandria. The slide went even further, with practices and teachings that helped the acceptance of the gospel in new gentile tribes as well as the dominance of church leaders. I would list praying to the saints and mother Mary to this list because that resembles the beliefs in gentile religions, revering and contacting the ancestors and having one or more female god characters in the pantheon of gods. I understand that all members of old churches cannot accept this kind of claims but that is my interpretation of what happened in church history.

Looking from the roots of Christianity, the Hebrew thinking, such changes would have been a no-no.

Your claims of Jewish beliefs are surprisingly one-sided. Until the destruction of Jerusalem, the Jewish interpretations of theological matters were diverse. There may have been teachers that did not believe in free will but I am fairly confident that many Jews assumed that humans have free will, at least to some extent.

The claim of Paul that we are slaves of either sin or God is perhaps polemic, strongly black or white, but well rooted in reality. Another comparison is to a child. Both slave and child may be partly metaphorical expressions but tell something important about the relationship between us and God.

I count myself both as a child and a slave of God and think that both are an honour. The Father and master takes care of his children and slaves, so I can be quite confident that God takes care of me.

The Father and master takes care of his children and slaves, so I can be quite confident that God takes care of me.

Yes, I can see you understood me (not)

carry on then

Richard

Is God dictaorial!

If the answer is Yes then He is not worthy of my worship.It makes HIm no better than any dictator who claims peace under his rule and leadership.

No that does not follow.

Parents are dictatorial to their two year-olds for a reason. I doesn’t make them bad in any way. So the correct question is whether God is giving us what we need. At one time, being dictatorial is likely what we needed and so we see this in the Old Testament. But I don’t think that is what we need now and we see this changing in the New Testament, where it is more about principles. Today I think we need even more – not just rules and principles but also reasons why and how it all fits into a big picture.