Having seen and read quite a lot of biblical inerrancy debates, I’d like to propose a few points to consider.

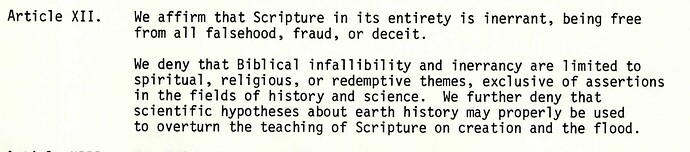

First of all, it is right and just to insist that the biblical inerrancy doctrine upheld by the well-known Chicago Statement is demonstrably wrong. I’ll briefly enumerate the main arguments supporting this conclusion, but won’t go into detail, as almost everyone here is well aware of these ideas.

- The analysis of literary forms and historical context reveals that the writers of the Old Testament creation narratives had no purpose to provide a precise, quasi-scientific description of natural phenomena.

- According to the Bible itself, the prophets have never participated in divine omniscience and will not participate in it till the end-time (1 Corinthians 13:9-12). Therefore, a prophet may well make a mistake while speaking about an issue which is not material to his or her God-inspired mission.

- Theoretically, a creator could have filled the created world with misleading evidence in order to deceive humanity. But God whom we encounter in the Bible will never do it: our God is not a deceiver. Therefore, one should assume a definite harmony between the Bible and nature, which is the other book of God, and avoid discarding the systematic and consistent knowledge about the age of the Universe that was obtained by physics, astronomy, geology, paleontology, and so on.

But to criticize the wrong doctrine is not enough. Criticism without affirmation (or without the equally strong and sound affirmation) is one of the reasons why the inerrancy doctrine remains widespread. Criticism without affirmation makes it easy to reinterpret the debate as a clash between the “high view of Scripture” and the “low view of Scripture”. Believers who don’t support the inerrancy doctrine but remain the full-hearted proponents of the creedal Christianity need to make visible and to uphold their own method of biblical interpretation. This method should be more sophisticated and coherent than the method of the inerrantists, but plain enough for a layperson to comprehend it, and conducive to a firm confidence in the doctrines of the Nicene Creed.

So, what should be the correct Christian way of reading and comprehending the Scriptures? First of all, it should be the Gospel-centered reading.

While reading the Gospels, one becomes assured that the birth, life, deeds, words, death, and resurrection of Jesus from Nazareth as described in the four canonical Gospels are the true representation of divine will and manner of action. This confidence should be partly spontaneous: one can’t become and remain a Christian without being captivated by the image of Jesus Christ. But this emotional engagement doesn’t need to be irrational. That’s why reading the Bible along with the book of nature and discerning divine action in nature is absolutely indispensable. To grasp the kenotic, self-humiliating manner of divine action in nature is to get ready for perceiving the crucified Christ as the embodiment of the Creator.

To comprehend that the Gospel narratives have correctly represented the true God is to get assurance that these narratives are theologically accurate. In other words, they are the true divine revelation. This statement doesn’t however meddle in the field of historical scholarship. The Church knows that the Gospels originated in the earliest Christian community fostered by the apostles. But it is up to historians to figure out (or, at least, to conjecture) the more detailed history of these texts.

Thus, the four Gospels are the key divine revelation and the centerpiece of the Bible (cf. Hebrews 1:1-2); the other biblical books’ authority may and should be proven by demonstrating their relatedness to the Gospels.

One can reasonably assume that the writings of the same Christian generations that have collected and written down the four Gospels are covered by the same divine warrant that ensures the theological accuracy of the Gospels themselves. These apostolic writings contain the important additional information about the Christian doctrine and discipline. Nevertheless, they should be read and interpreted in the light of the Gospel narratives about Jesus Christ – that is, about his birth, life, deeds, words, death, and resurrection. Nothing may be a universally applicable rule of Christian faith and life unless established by Jesus Christ.

As for the Old Testament books, the New Testament writers and Jesus himself have confirmed that the Old Testament “is inspired by God” and, therefore, “is useful for teaching, for reproof, for correction, and for training in righteousness” (2 Timothy 3:16). Nonetheless, there is an apostolic claim that, although it may seem arrogant, is of principal significance to the Christian exegesis of the Old Testament: the pre-Christian Hebrews were not able to understand the proper meaning of the Scriptures they were given by God. Only the Christian, apostolic, New Testament interpretation of the Old Testament is sound and true (2 Corinthians 3:13-16).

To sum it up, here are the two different but mutually supplementing approaches to the Bible.

The historical way of reading understands the Bible as the diverse collection of texts that had been written at different times and places to be finally united by the perspective of Christian faith.

And the theological way of reading, which should be basic for the Churches and individual believers, sees the four Gospels as the kernel of the Bible and the cornerstone of faith. The other New Testament books are the authoritative apostolic writings that must be read in light of the Gospels; whereas the Old Testament writings are the authoritative prequels to the ultimate divine revelation in Christ. These prequels must be interpreted according to the New Testament explanations.