This is a companion discussion topic for the original entry at https://biologos.org/blogs/dennis-venema-letters-to-the-duchess/vitellogenin-and-common-ancestry-understanding-synteny

As always, I’m happy to answer questions. Thanks for reading.

hey dennis. a question- did those researchers look at the entire genome for searching this sequence or they just chose this part of the genome? if they look at the entire genome it may indeed be a real vit pseudogene.

Very nicely presented, and I enjoyed the parallels from Prince Caspian.

From what I’m seeing and from looking back at his original articles, I’m beginning to get the impression that Jeffrey P. Tomkins’ main strategy here is to leave out nearly the whole pattern of evidence in order to focus in on the one small segment for which it so happened that he could provide an alternate explanation. He seems to pull off this sleight of hand in the following sentence: “The main piece of evidence for the vtg pseudogene is the presence of a 150-base human DNA sequence that shares a low level of similarity (62%) to a tiny portion of the chicken vitellogenin (vtg1) gene.” Through this small sentence, he gives himself permission to ignore the rest of the sequence alignment across all three genes, making his task easier by several orders of magnitude and giving him the working space to throw out all sorts of inferences about how tiny and tenuous the actual alignment is.

This 150-bp stretch was definitely the kind of sequence he would have wanted to focus on, since it was (a) relatively small, and (b) he could identify its ordained function as a “genomic address messenger”. For some reason, to identify a novel function for a supposedly homologous sequence is often enough for creationist audiences, who are apparently almost entirely uninterested as to why a sequence that serves a totally new function (almost always regulatory) would so closely match a coding region from a totally unrelated species in terms of both position and sequence. Whether this dismissing of impossibly far-fetched coincidences makes any sense or not for anyone the least bit interested in science, this strategy has worked well enough for creationists in the past, so it is no surprise that he uses it now.

In zooming in on this small region as the “main piece of evidence”, without a whisper about the extensive pattern of shared sequences and synteny throughout all three genes, he is able to make claims like: “a mere 150 base fragment of alleged similarity is but only 0.35% of the actual size of a real functional vtg1 gene in chicken and hardly representative of anything approximating a real pseudogene”, (from his original article in ARJ). From what I can see, such claims are palpably dishonest, since they would only be meaningful if the remaining sequences were entirely different between chickens and humans. My question was this: is this claim as dishonest as it looks, or did he just read an article that dealt with that that 150-bp segment, and went ahead without bothering to check the total sequence alignment. Tomkins’ articles are recent enough that I can’t imagine he couldn’t access sequence alignments.

I didn’t want to accuse him of dishonesty if he might have just been careless, but this just didn’t look good, so I decided to check up on his sources. Looking back at the Brawand et al paper from 2008 that he references as pointing him to this 150-bp sequence (his focus, definitely not theirs), they used the alignment of flanking genes to confirm synteny of the aligned regions and they exclude spurious sequence matches by using the genomic background as a control, while comparing the whole aligned region instead of focusing on one small segment. In fact, he states the following at the start of the ARJ article; “the sequence identified by Brawand, Wahli, and Kaessmann (2008) as being a vtg pseudogene is only 150 bases long”. This is an obvious misrepresentation, since they are clearly basing their conclusions and their statistical treatment on far more than just this small stretch of DNA. At best, he does not give a fair presentation of their findings at all, and at worst…

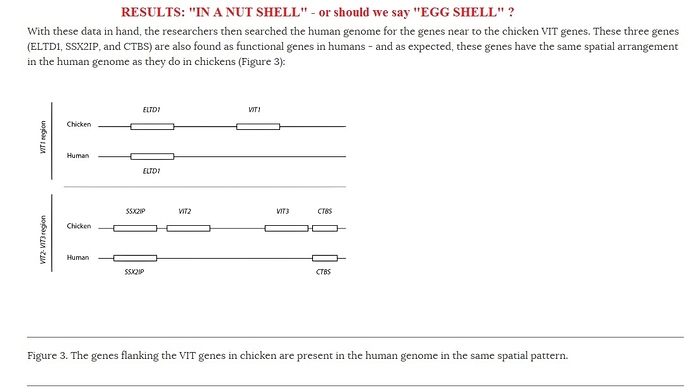

Tomkins’ version of the gene neighborhood synteny for these genes (in his original ARJ article) is also totally different from what you (and Brawand et al) have presented so far, but given the above, I might just go with your account.

I realize this might anticipate where you are going with this series, so I’m sorry if this is the case!

Hi Bren,

Yes, you’re definitely on track. The other thing he ignores is the VIT sequences in other mammals, which increase our confidence that we are looking at shared syntenic regions in the human and chicken genomes.

The main point of this post was to lay out the actual data - and in so doing, what Tomkins is saying is revealed as obviously incorrect (whether intentionally or not I cannot say, nor am I really that interested in that answer).

Hi dcs,

You can look at the paper to see the details. I’m sure they started with a simple genome-wide search, but using synteny to narrow down the region to look in greatly simplifies things. Why would looking genome-wide make you more confident that these sequences are “real”? The fact that they are in shared syntenic blocks with the chicken VIT genes is what convinces scientists.

Yes, you’re probably right to avoid guessing about whether these things are intentional or not. That said, I tend to prefer it when reading an article if I don’t have to keep checking the references to see if they are being misrepresented in some way, whether by mistake or on purpose. I believe ARJ claims to be peer-reviewed (within the creationist community obviously), so maybe the problem is that they are spread too thin and can’t find anyone with the right background to check their facts. Anyway, look forward to seeing how you respond to the claims of the article in the next post.

Dennis,

Not sure if you ever ran across this creationist critique of VTG pseudogenes: http://www.truthinscience.org.uk/content.cfm?id=3113

Thoughts?

-Tim

Hi Tim,

I did look it over, yes. It seems he’s trying to argue that the human VIT remnants are functional genes for making egg yolk. That’s so farfetched that even Tomkins isn’t arguing that…

Thank you Dennis. I don’t doubt you, but if asked by a creationist how would I explain why? It seems the author of that article is making a 2 part claim. One, even though mammalian embryos do not require yolk in bulk as do externally laid eggs, they do require minute amounts of yolk-like nutrients in a critical part of their early development. And two, since we don’t really know what this bit of genetic code does, given that it shares some similarity to other yolk-producing genes, maybe it is responsible for producing this minute amount of embryonic “yolk.”

So I accept that either one or both of those claims may be absurd. I just don’t understand why.

-Tim

I could be wrong, but I think DCS is asking whether Brawand et al only looked between ELTD1 and FP (or neighboring regions) for VIT1 remnants, and likewise for the VIT2 and VIT3 fragments. The answer is provided in the Materials and Methods: “Absence of VIT gene sequences outside of VIT syntenic regions was confirmed using tBLASTn against the entire genomic sequence.”

DCS, do you agree that these seem to be “real pseudogenes?” (I think they’re technically just shards of pseudogenes, but that probably doesn’t matter.)

if its true- then its a good evidence for a real vit. of course, its doesnt mean that its evidence for a commondescent (because other reasons).

You do realize that just because you can IMAGINE why hundreds of data points are wrong doesn’t place an obligation on your readers to think your conclusions are valid, right?

I can’t list all the times that I (or others) have presented the cumulative aggregation of perhaps 200 significant flaws or indicators regarding the flawed historicity of the Bible.

Evangelicals dutifully present their “cherry picked” explanation for each of these 200 (or more issues).

But at the end of the day, no objective observer thinks an ancient text can have dozens OF DOZENS of reporting problems and STILL think it is definitively reliable.

Hi Tim,

We can tell that the human VIT pseudogene fragments cannot be translated into VIT proteins - the fragments are small, and even those remaining fragments are riddled with mutations that would prevent their translation. The minute amount of yolk in placental mammals thus cannot come from these sequences.

Thanks Dennis! That helps…playing devils advocate though, and I’ve heard this mentioned elsewhere before, can’t even fragmented genes that are incapable of producing full contiguous proteins still transcribe amino acids or truncated chains? Is it outside the realm of possibility that such products could serve a nutrietive role in lieu of a full yolk for an embryo? Thanks!

-Tim

There are rare cases of RNA editing that may do something like this for some loci, but the VIT fragments in the human genome are so far gone that there’s no way RNA editing could “rescue” them. There is very little of these genes left.

Thanks Dennis. This makes a lot of sense. But following this line of reasoning, doesn’t this point hold true for most any severely degraded pseudogene? But for some reason none of the other examples out there seem to be compelling to creationists. I, perhaps like you, thought the vitellogenin pseudogenes would be more convincing for the fact that humans have no need for yolk production. But if the point is conceded that there are minuscule amounts of yolk-like nutrients produced in the embryo, then we lose some of the power of that point. And while mentioning that the gene is far too degraded to produce any protein needed to manufacture said yolk-like substances is valid, this is no different than mentioning the same thing about for instance a severely degraded olfactory pseudogene. So what then is unique about this example that makes it more compelling? Thanks!

-Tim

Hi Tim,

Vitellogenins are the genes used for bulk yolk transfer in egg-laying organisms. The minuscule amount of yolk found in placentals is not VIT based. So, there is no reason, from a antievolutionary perspective, to find VIT sequences in placental mammals, since placentals have no need for bulk yolk transfer. Evolution, however, predicts that placental mammals are descended from egg-laying ancestors, and thus may retain fragments of the VIT genes harkening back to that former way of life. If so, these fragments should be in blocks of syntenty conserved with egg-laying vertebrates. So, what we observe in placentals is exactly what evolution would predict.

Thanks Dennis. But I thought that VIT genes are for both the production of yolk and its bulk transfer from the liver to the oocyte? Am I wrong? Is the yolk produced elsewhere and the VIT genes then just transport it?

-Tim