I’ll pass on this one, George. Thank you for the invitation.

Yes, perhaps he was commenting on Copernicus. We don’t know, since he didn’t identify his target by name. Or, perhaps it was contemporary scholars interested in Cicero. There is some evidence for that hypothesis.

However, we can be certain that Calvin was geocentrist. He makes many references to that cosmology in his works. Almost everyone born before 1550 believed the earth was in the center of the world and motionless. University texts continued to teach that down to about 1650 or perhaps even later. Calvin knew basic astronomy well, including the facts (as taught in medieval and Renaissance textbooks) that the earth is round and that Saturn is a great deal larger than the moon–the latter fact underlies Calvin’s famous appeal to accommodation in his commentary on the fourth day of Genesis, where he notes that “the lesser light” (the moon) is actually not the second largest body in the heavens (after the Sun), but that Saturn is far larger than the moon.

Wow, that’s an interesting idea. I guess I am not sure, though, how to take that. The Sun is a medium star and doesn’t really represent the Godhead; so it was only by happenstance that his Trinitarian beliefs took him in the right direction, right? And holding on to that belief may have put him on the wrong side of astronomy when it advanced to finding other galaxies and bigger stars–or am I on the wrong track? Thanks.

Well that’s a stumper for sure…

But I think your point about historical relevance is all bound up in that “line in the sand”.

If Thomas Jefferson can be given a pass, while Jefferson Davis might not be given one, it has everything to do with the evolution of the “social mind” of Western Civilization (or at least English-Speaking civilization) sometime between the American Revolution and World War I.

So, too, then is the question of when did natural philosophers come to expect the right to “freedom of publication” for any treatise on nature they might imagine (or mostly so)?

One might argue that it was when the Vatican’s “police authority” over central Italy, or over most of Rome, was finally brought to an end that we could say this kind of religious authority over citizens came to an awkward end.

Certainly, prior to this date, Americans had come to expect this kind of freedom from religious coercion (on anything other than matters of sexual license). America was just an infant during the time of Galileo’s trials…

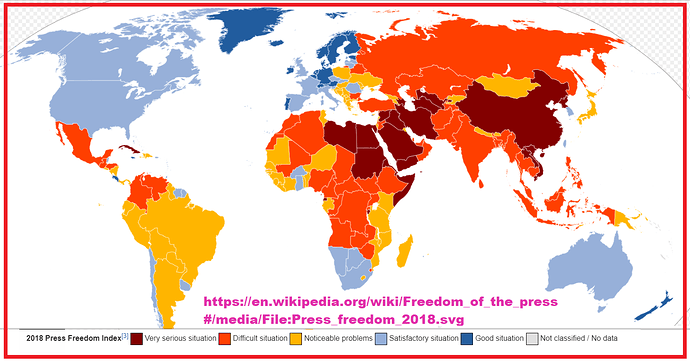

But the freedom of Science can only be expected (let alone permitted) where democratic values are permitted… hence the map below:

[CLICK ON IMAGE TO MAXIMIZE LEGIBILITY!]

Wow, Canada and the US are worse off than Denmark and Germany? I wonder how that is?

1.) PBS and NPR should go big or go home. When Eva Hamilton, CEO of Sweden’s public television network SVT, hears about the budget cuts and political controversies plaguing her American counterparts, she nods in sympathy . . . o o o

2.) Simple and fast can trump flashy and confusing. One of the most popular news services in Scandinavia is also one of the oldest. Teletext is a primitive, pre-Internet digital technology that broadcasts small bursts of text onto a television screen. It has developed since the late 1970s into a whole menu of information, like weather reports, sports scores, and traffic. Despite the fact that its interface is about as sophisticated as an Atari game, it’s simple, and fast, and millions of people in Scandinavia use it every day . . . . o o o

3.) Self-regulation works, as long as everyone’s on board. Scandinavia’s press councils are independent organizations, staffed and (for the most part) funded by the journalism industry, that were established to give readers a place to bring grievances against news outlets . . . . o o o

4.) Public broadcasting can (and should) prove to their audiences that they are non-biased. Because Scandinavian audiences directly fund their public TV and radio through a mandatory annual fee, they tend to feel a strong sense of ownership over what they watch and listen to o o o

and more o o o

Let me add something to this. Yes, indeed, the press here is very free in their work. But at the same time the image of the press is at the worst state it has ever been so that “journalist” has become a curse word. This happened after September 2015 and people to this day perceive a too tight bond between the government and journalism in the sense, that there hasn´t been any critical analysis of the action to open the border and critics have been misrepresented. This is not exactly my position, but indeed here has been an estrangement between the journalistic elite and the normal people, because of an overly representation of the progressive left in the mainstream media. The latest example here was the debate about the now legalized homosexual marriage and a perceived one-sided report and lack of representation from conservative political perspectives.

In summary, yes the situation now is still good, but it is going downhill since violence against journalists is on the rise and it will probably take many years and sincere change until their image will become better again.

A student of Freedom of the Press should know something important about its traditional role:

The Press is INCLINED towards defending the individual against Corporations and defending the individual against Governments.

And even when the press is in the few hands of major corporations, it is still a tendency.

The real world “tends towards liberalness”… because the very wealthy and the very powerful can take care of themselves.

You might want to consider a paper on “the line in the sand”.

Shrugging your shoulders and implying that there’s nothing to be said about human or institutional behavior in the 1600’s … or the 1700’s… or the 1800’s… doesn’t seem like much of a devotion to uncover what is True.

True. And big parts of the german society feel that the press fails in this role and have no trust in it anymore. That´s why I didn´t say anywhere that this development is not self-inflicted

Thanks for that correction. It had not even occurred to me (though perhaps it should have) that astrology came in those different flavors.

Since you’re apparently confident that you can uncover the Truth on this one, George, why not write that paper yourself?

This is an enormous historical topic in which I have no particular expertise from which to justify an opinion with enough confidence to share my thoughts in a public space. The closest I could come to doing so would be to say that (IMO) the Anabaptists had (in general) better ideas about religious freedom than any other early modern Christian groups–despite their obvious failings in the Münster rebellion. I last studied the Reformation formally 40 years ago, George. There’s been a vast amount of scholarship on it since then–and a great deal already in existence then–that I’ve never read. A number of historians then found “Enlightenment” ideas of political and religious freedom already common currency among various 16th century Anabaptist groups, all of whom came long before Jefferson to embrace “non-magisterial” churches, that is, churches that aren’t government run or government connected. (The Catholics, Lutherans, Calvinists, and Anglicans were all “magisterial.”) They put much stock in their own particular version of a “two kingdoms” theology, according to which the sword is for the kingdom of the world, not the kingdom of God. This is why, even today, many devout Anabaptists don’t even vote, and absolutely do not participate in the military or the police, even though they might acknowledge a certain amount of legitimacy for a non-Anabaptist police officer to kill an armed terrorist in order to protect innocent lives.

I’m not necessarily endorsing all that, George, so you can see already how complicated your question is for me. Asking me to write that paper would be asking me to have a prolonged bull session with anyone and everyone about ideas on which I have no particular competence to have sufficient confidence in any opinion I might offer. Speaking for myself, I’d much rather hear from someone who really knows something about this–who has a strong factual basis from which to opine–than from me.

Sorry to disappoint, but I will pass on your suggestion.

You are such a model for all of us on heights of restraint almost unheard of in public forums, Ted. While I’m not urging you to do what you’ve already said you wouldn’t, I’ll also venture that most of us could be forgiven for thinking an ounce of “non-expert” opinion from you on historical matters probably carries more weight than a ton of the shouting the rest of us are quite willing to do! ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

I’ve always admired that it was the work of a Catholic Priest who developed the insight into the Big Bang!

Inspirations for Good Ideas come from all sorts of places.

You write a very cordial “turn down” letter; nice work.

But I should point out that your whole thesis on how we should evaluate the Catholic Church’s (or any Church’s) treatment on scientific matters (excluding obvious bones of contention like embryonic stem cells, cloning, and sexual license) - - rests to a great extent on your very reasonable statement:

“. . . it’s hard to render an historical verdict against the Catholic church censoring various ideas, when at that time European authors just didn’t have intellectual freedom. That’s how things were done there then. We can certainly ask larger, meta-historical questions about whether that should have been the case, or whether religious authorities should have behaved like civil authorities, but we can’t easily answer those questions historically.”

I think you make a good argument that we have to be pretty circumspect to stay on the right side of “Historicism”! Here is a small patch of light in the Wiki article on Historicism in general:

New Historicism

“Since the 1950s, when Jacques Lacan and Foucault argued that each epoch has its own knowledge system, within which individuals are inexorably entangled, many post-structuralists have used historicism to describe the opinion that all questions must be settled within the cultural and social context in which they are raised.”

"Answers cannot be found by appeal to an external truth, but only within the confines of the norms and forms that phrase the question. This version of Historicism holds that there are only the raw texts, markings and artifacts that exist in the present, and the conventions used to decode them. This school of thought is sometimes given the name of New Historicism.

[Note: “The same term, new historicism is also used for a school of literary scholarship…”]

Dear Ted,

Thank you for the post. I grew up in Catholic household with a father as a deacon and uncle as a priest, so I have an intimate knowledge of the church today. My post was specifically based on the time period in question. The references that I have quoted were from a series of papers published after Pope John Paul II reversed the decision of the two inquisitions against Galileo. The papers were publishes in Museion 2000 from 1999 to 2000, with the final one asking the question: When will the church start its own Copernicus revolution?

Kopernikus - Auslöser einer geistesgeschichtlichen Revolution (5/1999)

Die Kopernikanische Wende - Befreiung vom aristotelische Geist (1/2000)

Galileo Galilei und der Durchbruch der modernen Naturwissenschaft (3/2000)

Der Inquisitionsprozess gegen Galileo Galilei (4/2000)

Galileo Galilei zum Verhältnis von Wissenschaft in Glauben (5/2000)

Wann vollzieht sich die ‘Kopernikanische Wende’ in Bereich der Religion? (5/2000)

This work, at that of mine is not to place blame, but rather to accept the past and move forward from it. With the hope that religions can use the same rigor that science does to test their basic principles, not to continue blindly supporting decisions made by politically motivated men in medieval times. They might find, like Galileo did, that there was a much more enlightened culture where science and spirituality coexisted - logically.

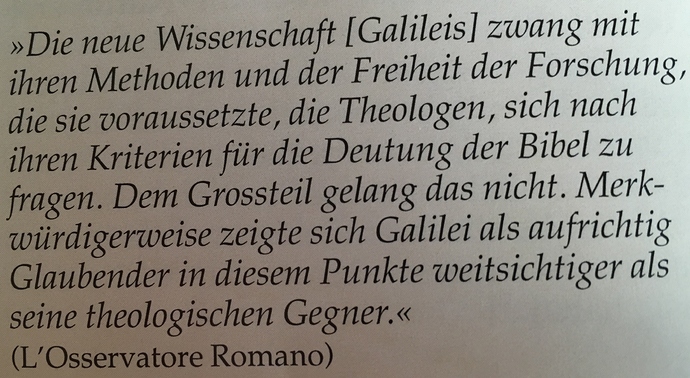

The new science [Galileo’s], with its methods and the freedom of research it required, forced theologians to ask for their criteria for interpreting the Bible. The majority did not succeed. Strangely enough, Galileo, as a sincere believer, was more farsighted on this point than his theological opponents.

The same thing happened at the inquisition of Joan of Arc. Her inquisitors could not outwit her logical defense. But, even though she won the verbal arguments she was still burned at the stake as a heretic. (See Mark Twain’s Joan of Arc)

In medieval times there was clear and present danger of speaking out against the doctrines that supported political power.

Dear Mervin,

I have read through The Great Copernican Cliché and you wanted to know what I thought about about it. The basic premise is this:

Copernicus removed humankind anthropos , inhabitant of this earth, from its metaphysically central place in the cosmos.

I think it misses the point about who was impacted by the Copernican revolution the most. For me, it was the Romans that had the most to lose by proving their Aristotelean worldview false. They had built a house of cards to control many monarchies, which they ruled from Rome - the center of the universe and the seat of god’s power on earth. Rome had rejected the teachings of Plato, Euclid, Pythagoras, Archimedes and Democritus when they declared Origen of Alexandria a heretic and denied his logic. (Remember it was Origen that had shown the oneness of Platonism and Christianity in his Stromata.)

Copernicus (Galileo), Luther, Zwingli, Calvin and Queen Mary were all threats to Rome’s house of cards and their ultimate power over mankind. Rome lost the battle, but do not underestimate how hard they tried to maintain their facade. Galileo was a focal point for Rome to attack. My contention is that their onslaught only accelerated their downfall. Galileo and, therefore, Copernicus became the battlecry for science’s revolution against Rome and its church. Many do not see past this great battle, back to the enlightened roots Galileo rediscovered.

Shawn,

I’m sorry, but you are failing to see the point of Danielson’s article and why it’s regarded as so important by many historians. First, let me speak to the highly relevant matter of expertise. Danielson has spent a lot of his life working in early modern literature, including astronomical texts. He knows as much about this as anyone, and much more than you or me. This doesn’t make him automatically right–no one is automatically right–but, he really does know what he’s talking about. When he says that no one voiced the “Copernican cliche” prior to the 17th century, he is in a very good place to say that with authority. He might be wrong; perhaps another scholar will at some point find one or two unambiguous examples that will disprove his conjecture. But, he’s seen more of the landscape than almost anyone else, and so his conjecture stands (in my mind) until shown to be wrong. Your personal viewpoint that the need for Catholics to defend a “house of cards” means that Copernicus was a serious threat simply isn’t historical evidence: it’s a bias from which you are dismissing a claim from someone who is familiar with the evidence.

What you need to do, Shawn, is not to offer a recent Papal statement about the church’s attitude toward Galileo and interpret it as evidence that Copernicus kept quiet b/c he feared persecution, or even execution. You need to produce 16th-century evidence that this is what Copernicus actually thought. We have no such evidence, none whatsoever. If this fact (about the state of the evidence) flies in the face of your particular viewpoint, then let me suggest that you rethink your viewpoint. Opinions should always wait upon facts, not the other way around.

Many of the relevant facts are summarized and/or explained in that great column by Tim O’Neill. For my part, let me remind you of just one enormous fact that is beyond dispute. Copernicus dedicated his book to Pope Paul III. In his dedicatory letter, he basically dismisses anyone who might raise biblical objections to his theory, in pretty blunt language, reminding his holiness that “mathematics is for mathematicians.” In other words, if you don’t understand the arguments in this book, zip it. Go mind your own business. (Kepler later did likewise in a similar tone in the preface to Astronomia nova.) Let me ask you, Shawn: did that show cowardice or fear of persecution on Copernicus’ part? A good reply won’t try to say that he knew he didn’t have long to live, b/c once that series of strokes came upon him the book was already in the process of publication and he then became too ill to work on it further. He wrote it all before that happened; it wasn’t as though he had just a few more weeks to live. Also, as O’Neill quite correctly points out, Copernicus’ ideas were informally published decades earlier, when he circulated his “Commentariolus” to friends. Anyone who wanted to know his opinions could just ask him. No church officials came after him, while several important ones gave him nothing but encouragement to publish. Any notion that he feared persecution is fanciful.

Until you can produce reliable information about Copernicus and his situation, Shawn, I will drop this conversation.

Does anyone else have questions of a different sort?

Is Copernicus a bit of a red herring?

I can easily imagine that the defenders of Galileo might have used the now-deceased Copernicus as a rallying cry as a “legitimizer” of the things that Galileo was working on.

If Copernicus worked openly, the idea that Copernicus’s reputation would be a SUPPORT for Galileo would make sense.

That’s precisely how Galileo opened his famous “Letter to Christina.” If the church had been fine with Copernicus, why all the fuss now?

What happened in between them was the full realization, on the part of the Catholics, that the Lutherans, Calvinists, and Anglicans were here to stay–at least for the time being. So, the church became more conservative in its overall attitude. Ironically, the Council of Trent (organized to combat Protestantism and to rid the Roman church of clerical abuses) implicitly allowed ideas such as those of Copernicus to continue to be read, b/c (presumably) natural philosophy wasn’t a matter of faith–that’s what Augustine and Aquinas had taught. But, Bellarmine ran roughshod over that notion, when he said that everything in the Bible is matter of faith, by virtue of “those who have spoken,” namely, the Holy Spirit speaking through the mouths of prophets and apostles. That type of literalism sounds just like Ken Ham today, and in the opinion of Catholic scholars (which I share) it was out of step with Catholic tradition on such matters.