Problems With A Localized Flood (full version)

Christians interpret the flood story as either a global flood, a localized flood or as a legendary narrative conveying theological truth. All three views purport take the account seriously as a part of sacred scripture but the first two are what are known as concordant interpretations. This means that whatever the Bible says happened must have happened and science should agree with it. The flood account should be interpreted literally. Of course, the problems with a global flood in Genesis are very well known and were outlined in a different section of this website. So problematic are they that a localized flood interpretation has developed in response. The idea is that the “whole world” as the author knew it was flooded, not the entire earth. Is this a credible interpretation of Scripture? It is sometimes pointed out that textual clues point to a more limited flood. As Iain Provan wrote in Discovering Genesis: Content, Interpretation, Reception : “the survival of ‘the Nephilim’ who are said to live both before the flood and after it (Gen. 6.4), and of the descendants of Cain who carry on various lines of work initiated by their forebears (Gen. 4.17–24)” would be two such examples. In addition, Genesis 2 describes rivers such as the Tigris and Euphrates using post flood geography. Assuming a global flood, it is hardly conceivable to imagine such river systems remaining the same before and after. Adam and Eve’s children could hardly populate the entire world in so little a time period and there simply isn’t enough water available to cover the world’s highest mountains. That God created more water and just as spontaneously made it disappear afterwards is rejected by many commentators as they feel the text implies God used pre-existing waters. These textual clues for a localized flood are based on concordant readings of the primeval history in Genesis. The flood was global or universal in the sense that it would have inundated humanity’s ancestral homeland or destroyed a very significant portion of humanity. It must be noted that genetics rules out all modern human ancestors descending from eight individuals aboard an ark. In the Holocene (roughly the last 12,000 years) humanity was pretty widely spread throughout the globe as well and a localized flood in the Mesopotamian region would not do justice to what Genesis actually depicts. Thus, for some the localized flood is pushed back many thousands of years (e.g. 50,000 years ago) when it would be more plausible to find a bottleneck for humanity. I find it difficult to believe Genesis preserves any history from pre-written cultures a few thousand years prior, let alone 50,000 years past. At any rate, this article will take a look at whether or not the text of Genesis is consistent with a localized flood and take a peek at two potential floods in the Mesopotamian region during the traditional time frame for Noah’s flood.

Meredith Kline writes in, Genesis A New Commentary , “A worldwide flood seems to be indicated by the comprehensive terms used here for its purpose (cf. 7:4) and afterward for its actual effects (7:19–23; cf. 8:21; 9:11, 15). But dogmatism must be restrained, for sometimes Scripture uses universal-sounding terms for more limited situations (cf. Dan 2:38; 4:22; 5:19), and a local perspective is evident at the critical descriptive point in the flood narrative (see note on 7:17–20).Still, the Gen 10 account of the repopulating of the world shows a vast area had been devastated, and Peter’s cosmic language suggests at least the severing of the central trunk of human history (2 Pet 3:5–7).”

Derek Kidner, in Genesis An Introduction and Commentary , writes of verses 7:19-24,” In themselves, these verses are not decisive for or against a localized flood: even the whole heaven (19) is likely, on the analogy of these chapters, to be the language of appearance (Paul uses similar speech hyperbolically in Col. 1:23). . . . The emphasis in Genesis is upon that group of cultures from which Abraham eventually came.’ If this is so, the language of this story is in fact the everyday language normally used in Scripture, describing matters from the narrator’s own vantage-point and within the customary frame of reference of his readers.”

Bernard Ramm relays similar thoughts in The Christian View of Science and Scriptures . He says, “Fifteen minutes with a Bible concordance will reveal many instance in which universality of language is used but only a partial quantity is meant. All does not mean every last one in all of its usages.” As an example he goes on to point out that all does not mean every person in the region was baptized by John in Matthew 3:5.

This is a hermeneutic I must agree with but heavily qualify. Yes, scriptural authors, like any other, can and do use hyperbole and universal language for limited situations but this does not necessitate or suggest we can apply them anywhere we want. There are Hebrew experts with linguistic and interpretive rules and then there is an army of poorly trained apologists and pious theologians who have been misusing concordances for a long time. There is a tendency of some to uncritically interpret scripture in light of scripture. While I respect the canonical dimension of the Bible, we must be careful not to dismiss the individuality of each work. God left us an anthology after all, not a singularly written book. Because Paul can use hyperbole does not necessarily mean Genesis can or is in this case. Paul’s Epistles and the flood stories in Genesis are two very different works written in two very different times with two very different audiences in mind. We would be better off looking at extrabiblical flood parallels for interpretative help with Genesis rather than seeking out hyperbole in Christian authors hundreds to a thousand years later. The context of the flood story determines its meaning, regardless of whether or not other Biblical works written much later use hyperbole. I take it as tautological that any Biblical author can make use of hyperbole or reflect a knowledge of things from their own perspective. There no need to dubiously appeal to other parts of scripture as if this somehow bolsters a localized interpretation of the Genesis flood. It does not. The localized interpretation of Genesis must stand or fall based on its own details, historical context and linguistic features in the text.

The Genesis Flood in Context:

So what are we to make of the Genesis flood in its own context? The three excerpts below show, in my mind how the Genesis flood is very much intended to be universal in scope. I use that word on purpose. The flood is not meant to be local or global. The author had no such distinction nor did he understand the world from a global perspective as we do today. The flood is described as universal. What we see is that creation itself is being undone by the flood. The order God established in Genesis one–the taming of the waters-- is reversed. Creation echoes are all over the flood account. Since I view creation in a universal sense I am inclined to understand its uncreation in a similar vein.

[1] Bill Arnold, Baker Exegetical Commentary on Genesis , writes: “The cosmic phenomena described in 7:11–24 are not some banal punishment for the sin of that ancient generation, but they represent a reversal of creation, or “uncreation” as it has been called. The priestly creation account of Gen 1 portrayed creation as a series of separations and distinctions, whereas Gen 6:9–7:24 portrays the annihilation of those distinctions.231 As the sky dome was created to keep the heavenly waters from falling to earth (1:6–7), here the opened “windows of the heavens” reverse that created function (7:11). When the “fountains of the great deep [t ̆ehoˆm]” burst forth (7:11), the cosmic order that had been fashioned from watery chaos returns to watery chaos (1:2, 9). Strikingly the sequence of annihilation, “birds, domestic animals, wild animals, all swarming creatures that swarm on the earth, and all human beings” (7:21), follows closely that of creation itself in Gen 1:1–2:3.232

[2] Robert Alter, Genesis Translation and Commentary (pg 33), writes “The surge of waters from the great deep below and from the heavens above is, of course, a striking reversal of the second day of creation, when a vault was erected to divide the waters above from the waters below. The biblical imagination, having conceived creation as an orderly series of divisions imposed on primordial chaos, frequently conjures with the possibility of a reversal of this process (see, for example, Jeremiah 4:23-26): biblical cosmogony and apocalypse are reverse sides of the same coin. The Flood story as a whole abounds in verbal echoes of the Creation story (the crawling things, the cattle and beasts of each kind, and so forth) as what was made on the six days is wiped out in these forty.”

[3] G. V. Smith (Structure and Purpose in Genesis 1–11,” JETS 20 [1977]: 310–11) came up with the following points of contact between creation and the flood (chapters 1-2 with 8-9). I have put the relationship from Smith in list format:

“(a) Since man could not live on the earth when it was covered with water in chaps. 1 and 8, a subsiding of the water and separation of the land from the water took place, allowing the dry land to appear (1:9–10; 8:1–13);

(b) “birds and animals and every creeping thing that creeps on the earth” are brought forth to “swarm upon the earth” in 1:20–21, 24–25 and 8:17–19;

(c) God establishes the days and seasons in 1:14–18 and 8:22;

(d) God’s blessing rests upon the animals as he commands them to “be fruitful and multiply on the earth” in both 1:22 and 8:17;

(e) man is brought forth and he receives the blessing of God: “Be fruitful and multiply and fill the earth” in 1:28 and 9:1, 7;

(f) Man is given dominion over the animal kingdom in 1:28 and 9:2;

(g) God provides food for man in 1:29–30 and 9:3 (this latter regulation makes a direct reference back to the previous passage when it includes the statement, “As I have given the green plant”);

(h) in 9:6 the writer quotes from 1:26–27 concerning the image of God in man. The author repeatedly emphasizes the fact that the world is beginning again with a fresh start. But Noah does not return to the paradise of Adam, for the significant difference is that “the intent of man’s heart is evil” (Gen. 8:21)”

After its destruction the flood narrative presents a new creation account (recreation!). Derek Kidner, Genesis An Introduction and Commentary , writes: “. . . we should be careful to read the account whole-heartedly in its own terms, which depict a total judgment on the ungodly world already set before us in Genesis – not an event of debatable dimensions in a world we may try to reconstruct. The whole living scene is blotted out, and the New Testament makes us learn from it the greater judgment that awaits not only our entire globe but the universe itself (2 Pet. 3:5– 7). “

The flood undoes the order God has established during his creative week. God is wiping the slate clean and starting anew. Creation terminology and parallels are littered over many aspects of the Genesis flood which is narrated as universal , regardless of the limited context of its author, which I take for granted. That the author had a limited understanding of the size of the earth does not preclude the author from actually believing and narrating that the entirety of the earth was flooded and all of humanity was destroyed. This localized flood view is based on a priori assumptions. It approaches scripture with a non-negotiable set of demands forcing specific interpretations to maintain concordant readings. That the author does not know the earth is spherical and people lived across vast oceans is no reason to force upon it a localized interpretation. This apologetic misunderstands the literary genre of the flood story and is motivated by the goal of salvaging the accuracy of the Biblical account which unfortunately is being held hostage for some by a literal, singular flood of epic but not global proportions.

The Created Order Appears Changed Post Flood:

As a further evidence of the universality of the flood, Genesis 9:2-3 reads: “The fear and dread of you shall rest on every animal of the earth, and on every bird of the air, on everything that creeps on the ground, and on all the fish of the sea; into your hand they are delivered. Every moving thing that lives shall be food for you; and just as I gave you the green plants, I give you everything. Robert Alter (ibid pg 38) writes, “Vegetarian man of the Garden is now allowed a carnivore’s diet (this might conceivably be intended as an outlet for his violent impulses), and in consonance with that change, man does not merely rule over the animal kingdom but inspires it with fear.”

Arnold Writes, “However, the new order is not altogether the same as the old, since it also involves an alteration of the food chain (9:3). Many readers assume this text implies something inherently virtuous in vegetarianism, since it was the original cosmic order (“plan A”), or inversely, something innately blameworthy in meat-eating. Others have assumed the change in human diet is a concession to humanity’s weakness. But in reality, the only implication of the text is that the new order is also accompanied by a change in the animals’ relationship to humans (9:2). The fear of humans is new, since pre-flood animals enjoyed a primitive fellowship with humans, now lost in the new natural order of things. Rather than placing value on either vegetarianism or meat-eating, this supplement of Noah’s deity with meat is part of a biblical progression toward holiness for humanity. “

Gerhard Von Rad writes, Genesis A Commentary , “The relationship of man to the animals no longer resembles that which was decreed in ch. I. The animal world lives in fear and terror of man. Previously ch. 9.1 assumes that until then the condition of paradisiacal peace had ruled among the creatures. Now man begins to eat flesh (cf. ch. 1.29). “The sighing of the creatures begins.” (Pr.) Answer: Just as God renewed for Noachic man the command to procreate, so he also renewed man’s sovereign right over the animals. What is new, however, is that God will also allow man deadly intervention; he may eat flesh as long as he does not touch the blood, which the ancients considered to be the special seat of life.”

Why on earth would a localized flood change the relationship between of animals and humans and the human diet the world over? Some scholars do dispute that Genesis 1-9 teaches pre-flood vegetarianism but even if that is rejected, we still have the relationship of man to the wild animals changing. This story is set in the context of global changes that affect the entire created order.

The soil also might have changed after the flood. We know that Adam’s action resulted in a cursed ground (Genesis 3:17-18) and toiling (“thorns and thistles shall it bring forth”). Cain also had to deal with cursed soil after murdering his brother. Genesis 4:12 reads: “When you till the ground, it will no longer yield to you its strength. . .”Genesis 5:28-29 reads: 28 When Lamech had lived one hundred eighty-two years, he became the father of a son; 29 he named him Noah, saying, “Out of the ground that the Lord has cursed this one shall bring us relief from our work and from the toil of our hands.” In Genesis 8:21 God vows to never curse the ground again. Alexander Thomas Demond writes in, From Paradise to the Promised land an Introduction :

“So God said to Noah, ‘I am going to put an end to all people, for the earth is filled with violence because of them. I am surely going to destroy both them and the earth’” (6:11–13). Once again we see how the continual violence of humanity has a direct bearing on the earth. Through the shedding of innocent blood, the ground is polluted, reducing its fertility. Consequently the task of tilling the ground had become almost unbearable by the time of Noah. . . . The episode following the account of the flood begins by describing Noah as a “man of the soil [ground]” (9:20) and focuses briefly on his ability to cultivate a vineyard that produces an abundant crop. This part of the story is clearly intended to highlight the dramatic change that has occurred as a result of the flood. Though the ground’s fertility was severely limited before the flood, now it produces abundantly. In this we see the fulfillment of Lamech’s comments regarding Noah in 5:29. “

Victor P Hamilton writes in The Handbook of the Pentateuch , “First of all there is a retraction by God of the curse placed on the ground (8:21; cf. 3:17), evidenced by the story of Noah’s vineyard, in itself a verification of the abrogation of the curse (9:20–29). Connecting 8:21 with 6:5, Gerhard von Rad (1972: 123) observes, “v. 21 is one of the most remarkable theological statements in the Old Testament: it shows the pointed and concentrated way in which the Yahwist can express himself at decisive points. The same condition which in the prologue [6:5] is the basis for God’s judgment in the epilogue reveals God’s grace and providence. The contrast between God’s punishing anger and his supporting grace . . . is here presented . . . as an adjustment by God towards man’s sinfulness.”

After the flood, Noah is called a man of the soil and he successfully plants a vineyard and drinks its wine (Genesis 9:20). The flood apparently has cleansed the earth of its wickedness and allows the soil to give its strength once again.

God Promises Not to Destroy the “Earth” with Future Localized Floods?

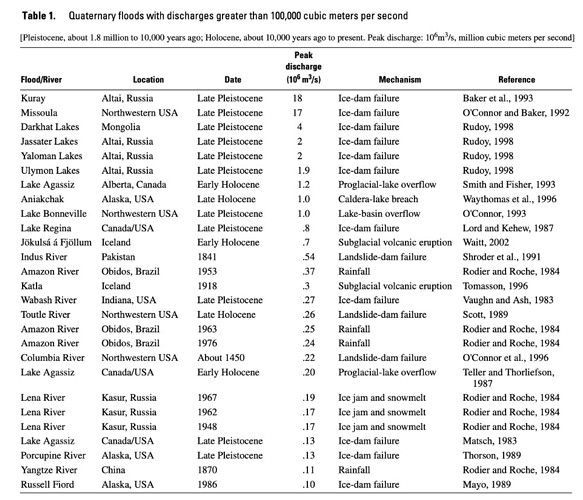

Genesis 9:11 has God saying, “And I will establish My covenant with you, that never again shall all flesh be cut off by the waters of the Flood, and never again shall there be a Flood to destroy the earth." Is God a liar when he said there will never again be a flood to destroy the earth? We know great floods are still very much common and prevalent in nature. The Indian Ocean tsunami in 2004 resulted in the death of almost a quarter of a million of people. What about the 1887 Yellow River flood in China? Or the Chinese river floods of 1931 which caused an estimated 150,000 people to drown in the first month and possibly a million more to die of disease and starvation after? Do they not qualify as great localized floods? The great Mississippi flood of 1927? Hurricane Katrina breaching the levees and flooding the majority of New Orleans? How about global climate change causing sea levels to rise slowly inundating coastlines? If we look at a table from Jim E. O’Connor and John E. Costa’s The World’s Largest Floods, Past and Present: Their Causes and Magnitudes from the USGS , we see there are many massive floods on the list that put the one in Genesis to shame. That image is found on the next page.

A concordist interpretation of the flood account seems to makes God out to be a liar. Floods still happen and there have been really significant ones before and after the putative one narrated in Genesis 6-9. It might be claimed that God was only speaking to Noah and his descendants but this is eisegesis as the covenant is meant for all people. We can’t even claim the Genesis flood wiped out a significant portion of humanity. As M. E. L. Mallowan wrote back in 1964 in Noah’s Flood Reconsidered : “. . . no flood was ever of sufficient magnitude to interrupt the continuity of Mesopotamian civilization, although as a direct consequence of the historic Flood we can observe evidence of a powerful impetus on the arts and crafts which underwent significant changes and developments after the Jamdat Nasr period.”

Was the Genesis Food Based on a historical flood? It could have been but this is by no means certain. Some exegetes think the overflow of the black sea could have been the historical impetus (Black sea deluge hypothesis) but to many this event was not rapid or significant enough to justify the necessity of an ark or many of the details in the Biblical flood story. Part of the extract of the article Was the Black Sea Catastrophically Flooded during the Holocene? – geological evidence and archaeological impacts by Valentina Yanko-Hombach, Peta Mudie and Allan S. Gilbert reads

“These hypotheses claim that massive inundations of the Black Sea basin, and ensuing large-scale environmental changes, drastically impacted early societies in coastal areas, forming the basis for Great Flood legends and other folklore, and accelerating the spread of agriculture into Europe. We summarize the geological, palaeontological, palynological, and archaeological evidence for prehistoric lake conditions, vegetation, climate, water salinity, and sea-level change, as well as submerged prehistoric settlements, agricultural development, coastline migration, and hydrological regimes. Comprehensive analysis shows that the Late Glacial inundation in the Black Sea basin was more prolonged and intense than the Holocene one, but there is no underwater archaeological evidence to support any catastrophic submergence of prehistoric Black Sea settlements during the Late Pleistocene or Early Holocene intervals.”

The article is well worth the read. For other scholars, events ca. 3000 BC could have been the impetus given rise to these Mesopotamian legends. Arnold writes: “The story itself likely arose from a specific historical flood that took place in parts of southern Mesopotamia around 2900 bce.” This is the flooding evident at Kish and Shuruppak. David Macdonald in T he Flood: Mesopotamian Archaeological Evidence , writes, “Within a few years, excavations of a third Mesopotamian site, Shuruppak, also uncovered a flood stratum (Schmidt, 1931). It is of particular interest because, according to the Mesopotamian legend, Shuruppak was the home of Ziusudra, the Sumerian Noah.”

Many scholars think the Genesis flood story rearranged some of the furniture of older Mesopotamian flood legends (e.g. the Gilgamesh epic and Atrahasis). Macdonald goes on to write that “many scholars specializing in the ancient Near East have concluded that the Flood stories of cuneiform literature and the Bible find their ultimate origin in the event attested to by the remains at Kish and Shuruppak (Mallowan, 1964, pp. 62-82; Kramer, 1967, pp. 12-18; Woolley, 1955, pp. 16-17” but also that there are problems here and evidentiary issues with a singular flood.

The Genesis flood description is nothing like these historical floods. MacDonald writes, “The Mesopotamian strata, whether at Ur or at Kish and Suruppak, testify only to a local flood which clearly left behind survivors and significant cultural continuity. The Ur flood apparently did not even cover the entire mound of Ur. . . . In the degree to which those descriptions are “rationalized,” any criteria for distinguishing between the biblical Flood and virtually any other flood disappear. “ If we allow such small-scale localized floods to serve as the impetus for the Biblical flood then we must admit we have lost any chance of falsification or corroboration. It is true that if we strip the Genesis flood narrative of most of its details then almost any flood could qualify as a historical kernel. But do we even need an actual singular flood? Given human populations tended to settle near water for obvious reasons, it is not surprising that so many flood stories are found throughout the world. Ancient people also found fish fossils and sea shells well inland and on mountains. These observations were documented by many cultures and could easily lead to stories and thoughts of massive global floods in the past.

David Montgomery in Rocks Don’t Lie , while narrating that Everest, earth’s highest cap, was once on the sea floor, writes: “But if you didn’t know about plate tectonics, how could you explain finding an old ocean floor on top of the planet’s highest peak? People around the world faced a similar question when they saw marine fossils entombed in high mountains. One way to resolve such puzzles is to assume that mountains don’t rise and that an incredibly deep sea once covered the peak, and thus the whole world. Another way is to assume that the rocks now exposed in the mountain somehow rose miles up out of the sea. Imagining that Noah’s Flood submerged the Himalaya is no less intuitive than the modern scientific idea that India is slamming into Asia and bulldozing up the world’s highest mountains in a process so slow one could not observe its progress over many lifetimes.” He goes on to later note that compelling evidence of a global flood for St. Augustine “was the widespread occurrence of plant and animal remains in rocks. Fossils seemed to tell the story as plainly as the Bible.”

The author of Genesis is hardly shown to be a source of factual information about meteorological or geological events that may have happened thousands of years prior. But yes, floods happened in the region. It is easy to assert a specific flood in the past led to these later fictitious legends but assumptions are not evidence. The problem here is many people think that a great flood would somehow give credence to the Biblical story but this misunderstands the literary genre of the flood and is a viewpoint imprisoned by concordist hermeneutics. Saying a flood in the past happened is not the same as saying “the genesis flood is true or happened.” The movie Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter is not true or validated due to the mere fact that Lincoln was a real person and the movie gets at least that much right. The majority of the details in the Genesis narrative are all but impossible and do not line up with reality I do not see how a historical kernel helps in any way here for concordist interpretations. As Macdonald concluded: “ Ultimately, the search for a local Mesopotamian flood upon which a rationalization of the Bible story can be based may prove as illusionary as the search for Noah’s ark.” Instead we should focus on the flood as literary and interpret it in light of its ancient context. How does it differ from its older Mesopotamian counterparts? Redaction criticism will be most helpful here as I believe noting the differences and changes made to Mesopotamian legends is the key to unlocking what it intends to teach us about God. We should also seek to understand how it fits into patterns in the Hebrew scriptures of humanity failing and God saving them via his grace.