Dale

March 11, 2023, 7:05am

1275

Speaking of trials…

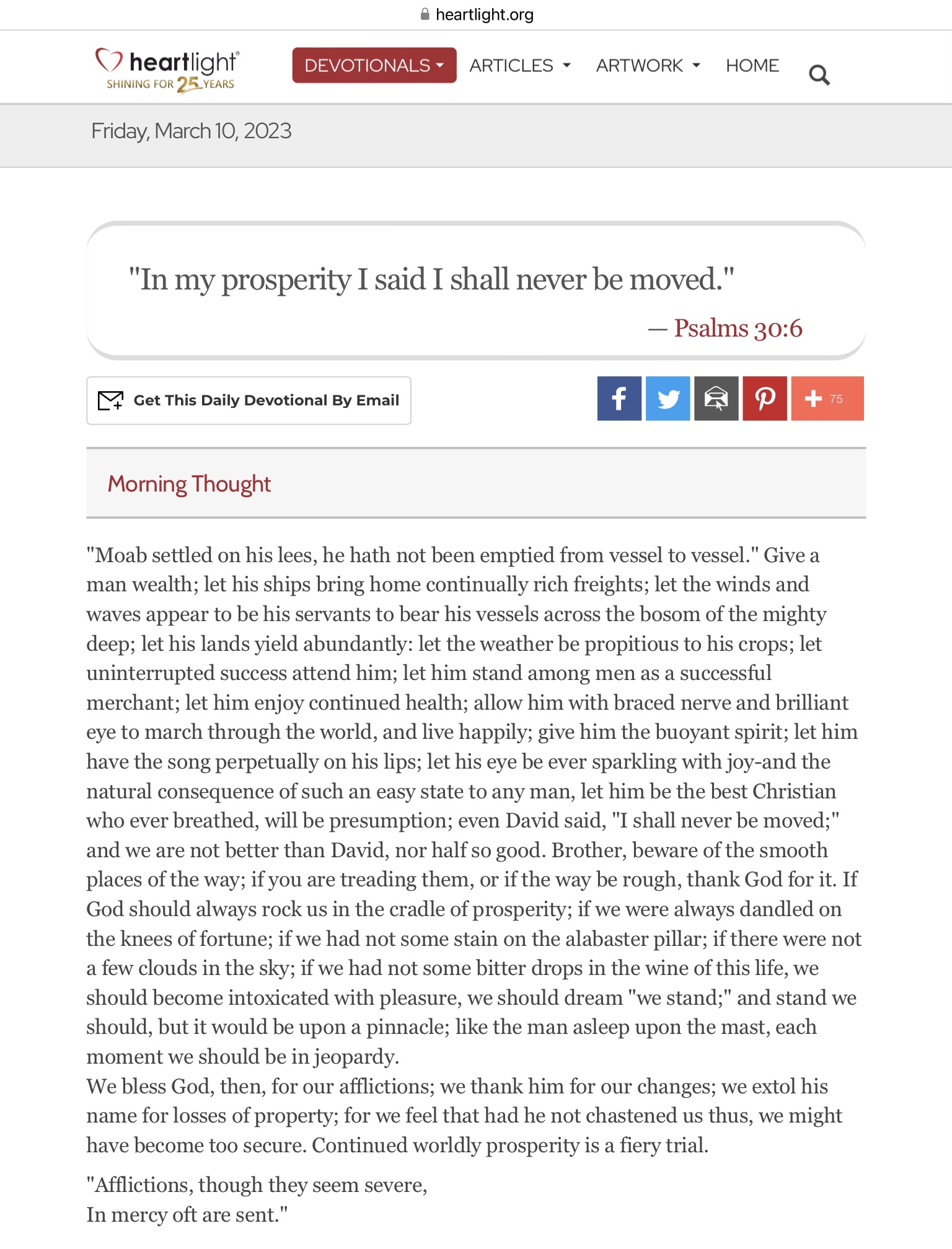

Spurgeon M&E (click image for better resolution)

The two lines of verse at the bottom are from a John Newton (the slave trader who became a Christian and wrote Amazing Grace), John Newton’s hymn "The Prodigal son"I

Afflictions, though they seem severe;

Although he no relentings felt

"What have I gained by sin, he said,

I’ll go, and tell him all I’ve done,

His father saw him coming back,

“Father, I’ve sinned-but O forgive!”

Now let the fatted calf be slain,

'Tis thus the Lord His love reveals,

If you like Southern Harmony hymn tunes, it’s a tune called “Tennessee”. As I wrote to a friend last evening who does like Southern Harmony:

About Southern Harmony, this is what I found first – I love it: https://youtu.be/1DIA1939hWM

This link is interesting, a German site:113 The Prodigal Son - Sacred Harp Bremen

It has a player (in the black/dark brown rectangles) – note the play button and below it, the different parts. But it is synthesized voice and 1 is almost unintelligible (you can kind of make it out if you are following along in the test). 5, all parts is way better.

And right below the player rectangles are YouTube links to two Sacred Harp choirs performing it.