Thanks to Michael Heiser, who passed away this week, I can take a more nuanced view of American Indian religion for instance. That the medicine men of old were following angelic spirits and not figments of their imagination or the devil himself. And while these spirits would eventually be judged, if that is the right term, Christ is now Lord over all.

“But we never can prove / The delights of His love, / Until all on the altar we lay.”

John H. Sammis

as quoted in this rather nice article on the recent work of God at Asbury which includes a brief history of the Wesleyan movement

“Savior, Savior,

Hear my humble cry;

While on others Thou art calling,

Do not pass me by.”

Fanny Crosby

as quoted in another article on the Asbury work, and what piercing words were written,

“Do you really want this?”

“It’s possible to enjoy the division of the church, your theological tribalism, or the secret sins you harbor, or to take twisted comfort in your complacency—to become deadened to the church’s decline and apathetic regarding the future. The Spirit of God is not safe.”

It has to do with presuppositions, among other things. Maybe ossification, habitual misthinking? ![]()

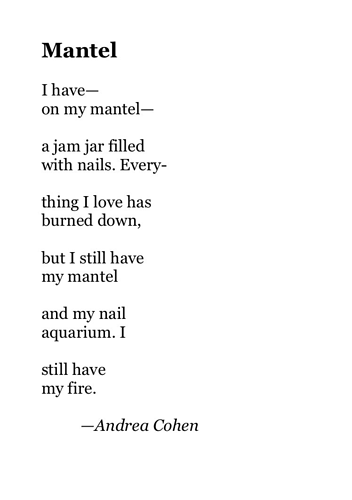

I really liked this poem I saw posted. I feel like it captures the feeling of reflecting on hard-learned lessons in life so well. I love how the it plays with the image of fire, from the image of sitting at a fireplace, where a fire is a comfort and a symbol of shelter and rest, to “burned down” where the fire is destructive, to the last line “my fire” with it’s double entendre of the comfort of the fireplace from the first image but also the suggestion of the internal drive that keeps a person surviving despite loss. Owning the fire also makes me think about the whole idea of deconstructing idealogies that no longer serve us (even though they may symbolize in some ways the totality of what we love). How much of is it passive “it has burned down” and how much is “my fire” that burned it all down?

It would certainly speak to someone whose house had literally burned down too, and all that was left was the fireplace and mantel.

I love the imagery.

I think it is good to keep impermanence in mind; it is what makes now imperative. I looked her up and found this one too that you might like given all the references to dust I’ve heard around here, most recently @Mervin_Bitikofer’s to the rock song Dust In The Wind which was huge for me too.

Dust

We funnel it between the stones.

What stones become is what

holds them together. A crushing

summer: white hydrangeas, in

dry winds, nod. In Adirondacks

we can’t fix, in a twilight beyond

repair, we recline, and an orange

tanager—what you asked

someone to come back

as—lights, and vanishes.

The photo below is of the Adirondack chairs I can’t fix and which require great care getting into and out of. Taken a dozen years ago it is amazing they still stand and somewhat support at all.

Just came across this from a different book while googling for William James quotes from his book The Varieties of Religious Experience. It is new to me but may speak to some of you too. I’m guessing, without having read the book, that this could be an answer to the question: why belief instead of stopping at agnosticism?

“It is as if a man should hesitate indefinitely to ask a certain woman to marry him because he was not perfectly sure that she would prove an angel after he brought her home. Would he not cut himself off from that particular angel-possibility as decisively as if he went and married some one else? Scepticism, then, is not avoidance of option; it is option of a certain particular kind of risk. Better risk loss of truth than chance of error,-that is your faith-vetoer’s exact position. He is actively playing his stake as much as the believer is; he is backing the field against the religious hypothesis, just as the believer is backing the religious hypothesis against the field.”

― William James, The Will to Believe

I agree with McGilchrist that religious belief is different in kind from empirical beliefs, being more dispositional than propositional in nature. But what else do we have to express them but the language of propositions? I suppose poetry would be preferable.

“I no longer wanted reincarnation to be true. I wrestled with not wanting to live hundreds of thousands of lifetimes to continue to pay off a debt I didn’t understand to begin with.”

I ran across this yesterday, doing more background reading on Kierkegaard’s Fear and Trembling. As I’m finding de silentio’s focus on defining faith both sharper and more confusing, I found this brief intro and quote from SK helpful:

Evans draws attention to a famous quote from Kierkegaard’s reply to Magnús Eiríksson’s critique of Kierkegaard’s ostensible position on the relation between faith and reason based on a reading of Fear and Trembling. Included in Kierkegaard’s response is the claim that ‘neither faith nor the content of faith is absurd’ for the believer (though its appearing so remains a continual threat, which Kierkegaard speculates may have been ‘the divine will’ [JP 6: 6598 (p. 301)]).Similarly, in a journal entry from the same year (1850), Kierkegaard adds:

The absurd is a category, the negative criterion, of the divine or of the relationship to the divine. When the believer has faith, the absurd is not the absurd – faith transforms it, but in every weak moment it is again more or less absurd to him. The passion of faith is the only thing which masters the absurd … The absurd terminates negatively before the sphere of faith, which is a sphere by itself. To a third person the believer relates himself by virtue of the absurd; so must a third person judge, for a third person does not have the passion of faith.

(JP 1: 10)

[The Routledge Guidebook to Kierkegaard’s “Fear and Trembling” by John Lippitt, page 61-62, (2nd edition, 2016; Kindle Edition).]

Returning to Kierkegaard’s character Johannes de silentio, who narrates Fear and Trembling. De silentio insists that the story of Abraham’s testing cannot be told solemnly enough, otherwise it makes Abraham’s faith seem cheap and gives the listener the entirely wrong impression:

People understand the story of Abraham in another way. They laud God’s grace for having restored Isaac to him—the whole affair was only a trial. A trial: this word can say a lot and a little, and yet the whole affair is over as soon as it is said. We mount a #[146]# winged horse and at that very instant we are atop Mount Moriah. At that very instant we see the ram. We forget that Abraham only rode upon a donkey, that it went on its way slowly, that he had a three-day journey, that he needed time to split the firewood, to bind Isaac, and to sharpen the knife.

And yet people praise Abraham. The orator might just as well sleep until fifteen minutes before he is to speak; the listener might just as well sleep during the talk, for everything goes along smoothly enough, without any difficulties from any of the parties. If there were someone present who suffered from insomnia, perhaps he went home, sat in a corner, and thought: “The whole thing is a minute’s business—you just wait a minute, then you see the ram, and the trial is over.” If the orator were to meet him when he was in this state, I think he would confront him with his full dignity and say: “Wretch, to let your soul sink into such foolishness. No miracle takes place, and all of life is a trial.” And as the orator continued with his outburst, he would become increasingly effusive, more and more pleased with himself, and although he had not noticed his face flushing when he had spoken of Abraham, he now felt how the vein in his forehead bulged. Perhaps he would have been dumbstruck had the sinner replied, in calm and dignified fashion: “But it was what you yourself preached about last Sunday.”

So, either let us write off Abraham or let us learn to be appalled at this enormous paradox that is his life’s significance, so that we might understand that our age, like every age, can rejoice if it has faith. If Abraham is not a nullity, a phantom, some bit of frippery we use to pass the time, then the error can never be that the sinner wanted to do likewise; rather, what is important is to see the greatness of Abraham’s deed, so that the man can judge for himself whether he has the vocation and the courage to be tried by something of this sort. The comical contradiction in the orator’s conduct was that he made Abraham into someone insignificant and yet wanted to prevent the other person from behaving in like manner.

Fear and Trembling, Søren Kierkegaard (Bruce Kirmmse, trans.), pp. 62-63.

Speaking of trials…

Spurgeon M&E (click image for better resolution)

The two lines of verse at the bottom are from a John Newton (the slave trader who became a Christian and wrote Amazing Grace), John Newton’s hymn "The Prodigal son"I

If you like Southern Harmony hymn tunes, it’s a tune called “Tennessee”. As I wrote to a friend last evening who does like Southern Harmony:

I think I understood maybe a fraction of what K wrote there - after a couple readings. I see what you mean about this not being ‘speed reading’ material. But some of the conclusions that tend to dangle just beyond the grasp of my immediate comprehension are intriguing enough to invite one toward the effort.

Merv,

Not for speed reading! And I’ve read the background parts that enculturate the reader in preparation for this section. So, I am throwing this out from left field.

I went back and did a bit of highlighting. Focus on the different time-related words. They create the contrast between how we SHOULD understand Abraham’s trial and how we DO understand it.

Kierkegaard emphasizes the enormous pain and anxiety to Abraham in the slowness of the process. He had days in which he prepared everything and travel with Isaac, in which he could have told God, “If you want Isaac, you will have to take him yourself. I won’t do this for you.”

We usually treat the entire trial as if it went quickly, is a moment’s work, nothing to really stress over. In doing this, however, we cheapen Abraham’s faith. We act as if it’s practically an automatic response to some normal demand of God. In cheapening Abraham’s faith, we cheapen faith itself.

Yes - that was the part that I think I caught on to there. Not to mention what conversations with Sarah must have been like (we’ve mused on that before in other threads long ago). “Bye honey! Will be out for a few days. Just going out to sacrifice the kid. Love you. Bye.”

Kierkegaard emphasizes Abraham’s silence. What he was told to do was unspeakable, and therefore he told no one. Even when Isaac finally asked – clearly the boy had done this with his father before and brought the animal along – Abraham gave the strange answer, “God himself will provide the lamb for the burnt offering, my son.”

The section I quoted above doesn’t address how Abraham would have broken the news to Isaac. How could he possibly tell him? How could they ever have any kind of relationship after this? No one talks about this.

In a different section of F&T Kierkegaard ruminates over 4 different ways the trip to Mt. Moriah could have played out. In the end, though, every other option seems to end with Isaac or Abraham losing faith. Which makes the biblical version all the harder; both men seem to come out with greater faith, and joy, and a continued normal father-son relation.

The narrator, de silentio (the Silent) repeatedly emphasizes that faith is a marvel, beyond human comprehension or accomplishment. He cannot understand it.

The implication is, that if we think we can do this all easily, we don’t understand it either.

So those who pressure others to turn on faith the way they might a light switch are shoddy salesmen misrepresenting the merchandise or clueless?

I think Kierkegaard demonstrated agreement. Although from a different angle. In his culture there was a wider assumption that everybody was already a Christian. He was actually demonstrating that “easy faith” was of no value, whether one called oneself a Christian or not.

Fear and Trembling magnifies the challenge and cost of faith at every possible level. That isn’t usually used as a selling feature.

I am not so sure about Isaac. It seems it may have affected his parenting a bit with the twins.

A good point. I think it is a mistake to think we can choose or reject belief as a rational decision, though sometimes I think that like love, we can act in faith though we doubt and something can grow from it.

No question there. Dysfunctional families abound in the Bible. Isaac and Rebecca do seem to have mirrored Abraham and Sarah in their favoritism for different sons. So, the standard for “normal” then seems pretty low today.

At the same time, Isaac continued to follow the God of his father. There is no indication (I think) that Isaac held a grudge against his father or God for having been willing to sacrifice him. That seems as miraculous as the faith that allowed Abraham to obey God.