(Posted originally by poster who wished to be removed from forum, but we have retained their post out of courtesy to those who responded to it. -jpm, moderator)

There is a common belief that because humans and primates share a high percentage of genetic similarity, we therefore descended from a primate ancestor. The problem is that this conclusion is asserted, not demonstrated, and the evidence does not actually support a smooth, continuous line between primates and humans. The phrase “98 percent similarity” has been repeated so often that people treat it as a proof rather than what it truly is, which is a misleading statistic based on select comparisons. Genetic similarity alone does not imply ancestry. A pig’s heart matches human tissue closely enough for transplantation, yet no one argues that pigs are proto-humans. Genetic similarity simply shows that life shares a design framework, not that one species gradually transformed into another.

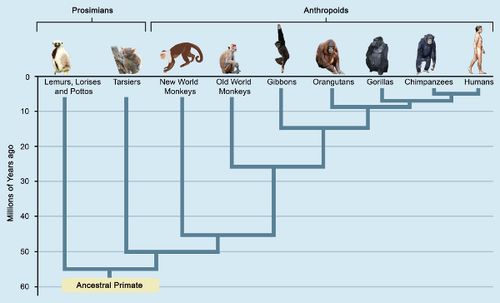

When scientists speak about a “common ancestor,” what they mean is that there should have been a species that branched into two lines. One line supposedly leads to modern primates and one to humans. However, the pivotal species required for this theory has never been identified. There is no fossil, no full genome, no verified transitional organism that sits at the branching point. What exists are models, reconstructions, and hypothetical trees. There is no empirical chain connecting modern humans to any primate ancestor through a series of gradual increments in cognition, language, symbolic reasoning, or consciousness.

This absence becomes even more pronounced when we consider the nature of consciousness itself. Evolutionary branching typically produces gradients. There are intermediate strengths, transitional forms, partial improvements. This is true across insect evolution, plant evolution, fish evolution, and nearly every biological system. But in humans, consciousness appears as a qualitative leap. Symbols, self-awareness, abstract reasoning, moral responsibility, complex language, artistic conception, spiritual intuition, the capacity to choose against instinct—these do not emerge as shades of grey in the fossil or cognitive record. They appear fully developed in one lineage only, without partial prototypes in any other species. There is no ladder from primate cognition to human consciousness. There is a gulf.

Genetics only deepens that gulf. Between humans and primates are significant differences in gene expression, neural architecture, speech pathways, regulatory sequences, and uniquely human accelerated regions in the genome. These differences are not incremental. They are categorical. If humans truly descended gradually from primates, we would expect a spectrum of intermediate species with increasing cognitive complexity, partial speech modules, incomplete symbol systems, and half-developed neural circuits. Instead, there is a sudden appearance of modern cognitive capacity.

Even within the hominid fossil record, what we observe are distinct categories: hominids that operate almost entirely by instinct, with limited symbolic behavior, and then the sudden emergence of Homo sapiens with full cognition. The missing intermediates are not minor gaps. They are fundamental discontinuities. In this light, the biblical account of Adam receiving the breath of life captures the very phenomenon that evolutionary theory struggles to explain. Primates and hominids may have existed in many varieties, but the soul and consciousness of humanity arrive abruptly, not as an evolutionary slope but as a distinct moment in the human story.

There is also the historical layer that the text of Genesis presupposes. Cain fears being killed by others who already exist beyond his family circle. This implies populations outside the line of Adam, populations that may not have shared the spiritual nature that Adam and Eve received. It also aligns with the possibility that many hominid varieties existed before the flood and were swept away, leaving only the lineage connected to moral agency and divine image.

Taken as a whole, the scientific record, the cognitive discontinuity, the genetic architecture, and the narrative structure of Genesis converge on the same conclusion. Humanity is not a by-product of primate evolution but a unique creation placed within a world where many biological forms existed before and around us. Our consciousness, our moral nature, our capacity for abstract thought, and our sense of the divine do not come from primates but from an entirely different source. The jump is too large, the intermediates are missing, and the evidence supports distinction rather than descent.

This is not anti-science. It is simply refusing to treat assumptions as conclusions. Information does not equal understanding, and similarity does not equal ancestry. What separates humans from primates is not two percent of genes but an entirely different order of mind, meaning, and destiny.