Then how is it that chimps share more DNA with humans than they do with other apes? How is it that gorillas share more DNA with humans than they do with orangutans? Why do we see this tree-like pattern that includes humans?

Well the issue would be why do we see some things not pop up in the fossil record until after a certain amount of time? We can see where one species had a mutation and after that in many of their lineages were see it. But when we go back to their ancestor we don’t see it.

It also does not line up with how we see in genetics outside of seeing that it following the same pattern of evolution. Such as single celled organisms evolving into multi cell organism and so on.

Your idea is basically a literal creationism where God created fully developed creatures at the head of families of that expressed its differences through adaptation. Or is that incorrect. Technically, I guess the genetic makeup for all of us was a potential inside of the original single cell organisms that took billions of years of natural selection to tease out. Sure it could work if God did create complex full developed species , but that’s ignoring the fossil record leading up to those families.

@Henry_Dalcke you say in your notes that a kind is about the taxonomic level of family. Would you mind expanding what you mean by that, please?

We don’t ‘see’ these tree like patterns. They are part of our >interpretation< of the observable data.

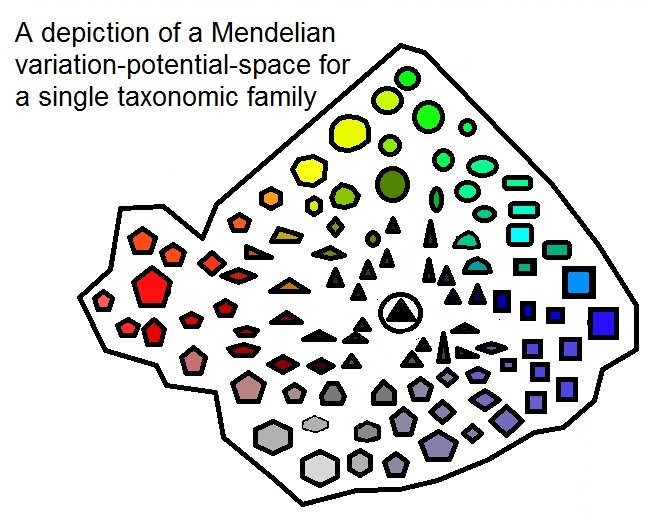

According to Mendelian inheritance, the variation potential of a sexually reproducing life form is depictable as a country on a map. It has a certain fitness landscape and borders. An individual phenotype represents a coordinate within that “country”. Think about it like this:

Now let’s envision two neighboring variation-potential-countries, ok? One for the Apes and one for Humans. The position of a certain Individuum within each landscape can now be close to the borders of each neighboring country, or it can be more up-country. If, say, an Orangutan is positioned more inland than a Chimp, it’s possible that the Chimp is genetically closer to the humans behind the fence, than to the Orangutan, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that it’s related to humans.

You assume that rock layers represent millions of years. That’s not necessarily the case. If they represent flood deposits that happened in just one single flood event, all fossils have lived at the same time. So all you see in the fossils is fine-tuning adaptation to individual habitats - which is entirely compatible with the kinds-concept. It’s all a worldview-dependant interpretation at work, here.

Well, that’s a tricky thing to explain, actually, as the boundaries between two kinds are not clearly definable due to a possible neighboring and overlapping of variation ranges. Depending on the width of a certain variation range, a biblical kind could very well be overarching more than just a taxonomic family. If the variation range is narrow, though, it could be on an even lower level than that of a family. It depends on the width of the variation range spanned by recombination and epigenetics.

OK, thanks. That does seem a bit fuzzy. So, if one cannot pinpoint what a kind is analogous to, how does one empirically detect their existence? It also make is tricky to understand what a kind is. If you can’t clearly define it, doesn’t that make it hard to convince others of its existence?

Perhaps, if we look a for instances. I’m a bug guy (insects and spiders) so you’ll have to forgive me for picking a ‘for instance’ that is in my area of interest. So, Calopterygidae and Coenagrionidae represent the families of broadwinged and narrowwinged damselflies respectively. Uder the ‘kinds’ system would you see broadwinged damselfly genera as all coming from a single broadwinged damselfly ‘kind’ or is more that all damselflies come from a single damselfly kind? What about the relationship between damselflies and dragonflies; would these be represented by different kinds or would all the odonatans have come from a single kind? If so, that would make the odonata kind more analogous to order level taxonomy than family level. How far down the insect taxonomic tree should I be look for insect kinds?

I guess what I am trying to say is that it is all very well and good running an experiment and drawing a conclusion from it. But I am interested in how that conclusion actually works in practice. In other words, what happens when the rubber hits the road, if you will. Looking forward to reading your thoughts.

It’s not just geological layers but various forms of carbon dating and things like tree rings to determine climates and seeing those patterns elsewhere. There is a reason why almost all scientists across dozens and dozens of fields land on the same opinion based on data including from oceans that would have already been covered in water and genetics are doing a lot to back it all up.

What’s the scientific evidence that the geological layers are actually thousands of years and not millions of years old?

Well, you exactly hit the bull’s eye of the problem, here.

In my paper I say that you cannot possibly find out which kind anything belongs to by looking at phenotypes, as you cannot determine the width of their Mendelian variation ranges, hence you don’t know where to set the borders between two kinds.

That’s exactly the point.

But guess what: the evolution theory has exactly the same problem - only seen from a different angle.:

Variation by mendelian recombination plus epigenetics doesn’t change the genome - it only changes the gene expression. Therefore it’s limited. But nobody can determine its borders. Evolution, though, can only be evidenced by finding a phenotype that’s outside these borders! But where exactly is “outside” of unknown borders? You have the exact same problem for the exact same reason: you don’t know the width of the variation range and therefore cannot distinguish between phenotypes encoded in the variation range and phenotypes exceeding it.

Even radiometric dating and dendochronology are based on unprovable assumptions. You cannot generate a serious argument for deep-time, here.

So why does your synthesizer model work for felines, but not for hominids? Is there a scientific principle here?

The number of parameters times the gradual resolution of the parameters that a synthesizer has defines the width of its variation range.

Parameter-number times parameter-values equals variation range.

Now, there’re synthesizers with 4 parameters which have 5000 values each and synthesizers with 850 parameters with 120 values each.

Which synthesizer spans the wider variation range?

That is a bit tricky question of course. Even if the variation ranges are comparable in size, that doesn’t mean that they actually overlap or are neighbouring closely. Why? Because we’re talking multi-dimensional parameter spaces here. Some parameters may cause phenotypic aspects that are similar, while others cause big phenotypic differences in some other aspects.

That’s why we often see shared traits and big anatomical differences at the same time from animal to animal or in other areas in the biodiversity.

What assumptions do you think radiometric dating or dendrochronology are based upon? Do you think there is any way that someone could try to cross-check those assumptions?

So, to answer your question why my Synthesizer model doesn’t work for humans , but for Apes:

Oh, it does for both, of course. You have to think of apes being represented by a more complex synthesizer to be controlled by the genetic algorithm than the synthesizer representing humans. While the ape-synth can produce a large number of sounds, the humans- synthesizer cannot produce sounds that are similar to those the ape-synth can produce.

I’m not a geneticist (I’m more of a whole-organisms guy) and a theologian by background, so forgive me if I am misunderstanding you here. It sounds as if you are saying the ‘kinds’ approach to speciation and an evolutionary model of common decent both suffer different expressions of the same fatal flaw. Doesn’t that kind of torpedo your entire argument that evolution is wrong and YEC is correct?

On an aside, insect and arachnid taxonomy no longer operates on a phenotype only approach whereby genera are assigned to families by comparative anatomy and behaviour alone. For example, recent genetic studies of the spider family Tengellidae resulted in the family being made obsolete and the genera being merged into the family Zoropsidae. This happened despite Tengella expressing a markedly different phenotype to many other zoropsids. But again, I am not a genetics guy so may have misread you.

We do not really “prove” anything in science. But radiometric dating and dendrochronology, as well as the consilience of ice cores and varves, constitute overwhelming evidence that the YEC timeline is unsupportable.

Why not? Not liking evidence does not invalidate it. Use the search function for this forum, especially postings by James McKay aka Jammycakes.

Radiometric dating is based on at least three assumptions.

1: has the ratio between - let’s say - C12 and C14 equalized out in the atmosphere? It’s assumed that it has. Unprovable.

2: did the decay rates change over time? Unprovavle.

3: has there been a loss of end products due to environmental conditions? Unprovable.

Radiometric dating is not an accurate science.

Dendochronology is based on the assumption that tree rings depict years or seasons. That is not necessarily the case.

This is not my field of expertise, though, so I could only rely on sources that you would eventually not find to be credible.

Why did it change? As radiometric decay is determined essentially by the atomic and nuclear geometry, that part is a given. That leaves the two nuclear forces and the electromagnetic force. How were these altered, and what are the cosmological implications?