Mercury refused to follow Newton’s Laws of Gravitation. Reality has this funny way of not caring about the laws we write. We have had a tough time telling Reality how it should behave.

- Who said Newton had everything correct? Obviously his “little balls of invariable mass” were false.

- But so what?

- Motion, as the concept is understood in any other context than relativity theory, consists in having a variable location in space. If there is no space, then the relativists obviously must mean something different by such words as ‘motion’ and ‘uniform motion’ and ‘spatial reference frame’ from what everybody else means by these words.

And so it is with the Law of Non-contradiction. We can stamp our feet and say that it is a contradiction to act as both a particle and a wave, and yet those darn things keep acting like both.

Who is stamping their feet about this? Seriously

Once it is observed as a particle, it’s a particle, if it changes back into a wave, I don’t see the contradiction.

Kind of like how people can be mindful and then mindless.

For example: Is it ok to tell someone it is wrong to take personal experience as normative against someone else’s experience, when you just previously said it is delusional to have a conversation with God?

This type of self-contradiction seems patently false.

Heidegger saw the nothingness as capable of contradiction, maybe even self-contradiction. So should it then follow that a human being can contradict them self?

And in thinking about it further, I see a strikingly relevant example here of the postmodern belief (or is it judgement) that a literary text is ultimately free from judgement.

There can be charity and a giving of the benefit of the doubt. But that becomes ever more tenuous as the contradictions persist and explanations are not forthcoming.

It does make sense to me, but even if it didn’t, I’ve long since disabused myself of the notion that reality has any obligation to conform to my intuition.

Since I’ve left the church of physics I don’t really count as a physicist anymore, but I won’t let petty considerations deter me. I’d say you can develop intuition about any complex system you’ve spent a lot of time working with. That includes the literal behavior of physical systems – including quantum mechanical ones – and the behavior of things like mathematical systems.

I’ve seen very little effect of postmodernism on the practice of science. Some criticism of scientific practices, e.g. the practice of doing genetic research only on a small number of wealthy populations, could be framed in postmodern terms, but I don’t see any real need to. I have seen a few postmodern critiques of science, in whole or in part, but not for several decades. Perhaps I stopped looking. My impression then was that there were more really bad critiques than good ones. Part of the problem may be the (to me, ludicrously) opaque language a lot of postmodernism has been couched in, both because it makes much of it impenetrable to those outside the club and because it makes it harder to detect poseurs to spout pretentious gibberish. Scientists tend not to have a lot of patience with deliberate obscurity. (Except when it comes to giving things unnecessary acronyms and Latin names, of course. Then it’s kosher.)

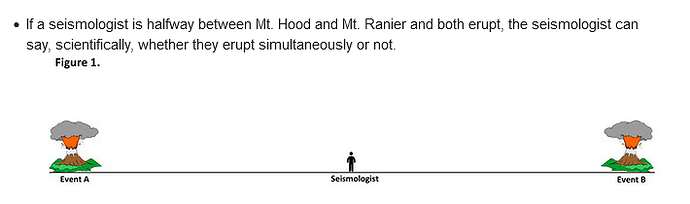

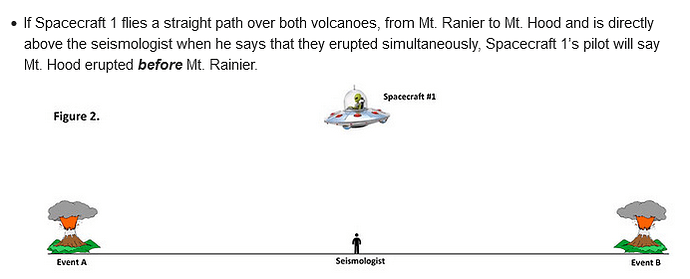

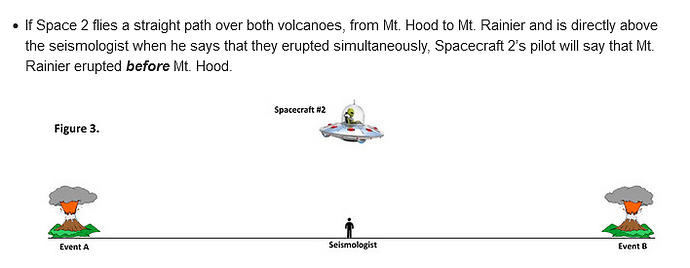

- I suppose it would to anyone who believes the Law of Non-contradiction can be important in Logic but is not a Law in Physics. The fact that each of two clocks in motion at some velocity relative to each other can “tick” slower than the other or that two measuring rods in motion at some velocity relative to each other can “be” shorter than the other may be deemed “great fun” when playing with a naive “newbie”, but it’s annoying and exasperating when the newbie is trying to get a straight answer. Especially when the same kind of stuff finds its way into a pulpit or a conversation between two believers in Jesus’ resurrection.

- “Yes” is a less than satisfactory answer to the question: "Well, is it true or false?

- Especially when someone says “We have experimental proof” of one or the other but never both.

The Law of Noncontradiction applies to contradictory propositions. ‘Clock A is faster than clock B in reference frame 1’ and ‘Clock B is faster than clock A in reference frame 2’ are not contradictory propositions. The expectation that there should be a universally valid clock is an intuition or an assumption, not a logical principle.

Note that you can describe all events in terms of a single reference frame (at least in Special Relativity – I’m no expert in GR) but it gets very messy and there’s no obvious reason to do so.

![]() And then there would be the scientists in the military, speaking of undecipherable acronyms and initialisms.

And then there would be the scientists in the military, speaking of undecipherable acronyms and initialisms.

We could always talk about spacetime slices. ![]()

- You’re “preaching” to the wrong person. I’m a veteran of “the Relativity-Antirelativity War” leading up to the 100th anniversary of the publication of Einstein’s 1905 article: “On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies”, which brought “wanna-be” minions and “newbie cranks” like me from all walks of life, foreign and domestic.

- I’m jaded by the claim you state, that there is no contradiction between propositions held by observers in different reference frames. And when all is said and done, the knowledgeable Relativist assures the wanna-bes that “the youngest twin” [in ‘the Twin Paradox’" is the one with the shortest worldline]. Go and find someone less experienced to swallow the claim.

- “A universally valid clock” is a proper starting axiom, but certainly not an intuition. It’s one of several “Absolute Truths”, without which the universe descends into relative madness, IMO.

- "If there is no standard that consists of things that are permanently the same distance from each other, such as is provided by the notion of absolute space in classical mechanics, then there is no meaningful content to the “proposition” that any two things are any specific distance from each other, a fortiori. no meaningful content to the “proposition” that such a distance has changed and still more so no meaningful content to the “proposition” that such a distance is changing either at a uniform or at a nonuniform rate.

- "If there is no standard that consists of something that happens everywhere and at a constant rate, such as is provided by the notion of absolute time in classical mechanics, then there is no meaningful content to the “proposition” that anything happens at any given rate and, a fortiori, no meaningful content to the “proposition” that such a rate is either uniform or non-uniform.

- “Similarly, if there is no standard that consists of a set of masses that are always and everywhere in the same proportions to and having the same differences from each other, such as is provided by the notion of absolute mass in classical mechanics, then there is no meaningful content to the “proposition” that any physical object has one mass rather than any other and, a fortiori, no meaningful content to the “proposition” that two physical objects have the same mass or have different masses, or that one physical object has either the same mass or two different masses at two different times, or that a physical object has a different mass for one observer from that which it has for another observer.”

Y’all remind of the recent Nature review of “Hawking’s Final Theory.” Here’s the end:

Physics versus philosophy

The second source of irritation is Hertog’s scorn for philosophy. He treats philosophers — as Hawking did during his lifetime — as rivals who think about concepts such as whether there was a Big Bang or not, and suggests that physicists love one-upping them by applying mathematical approaches to what they think are philosophical questions. But that mistakes what philosophers do. Whereas scientists study the natural world, philosophers of science study how scientists study the natural world. Hawking and Hertog’s attitude reminds me of the lament attributed to Socrates about those who think their knowledge about one thing entitles them to think they are similarly knowledgeable about many other things.

Hertog’s treatment of Hannah Arendt, one of the most important philosophers of the twentieth century, is particularly ludicrous. She and Hawking each said they are against a “view from nowhere”, which Hertog interprets as meaning that “Hannah meets Stephen”. With this, Hertog seems to urge fellow theorists to deny the classical picture that the cosmos has “a definite spacetime with a well-defined starting point and a unique evolution”. Arendt, however, criticized the theoretical and mathematical language that claims ultimate objectivity, detaches language from common sense and distances our understanding of the Universe from experience — a line of reasoning that has nothing to do with Hertog’s.

By the end of the book, I couldn’t help but recall a remark by the Soviet physicist Lev Landau — which Hertog quotes rather dismissively and without attribution — that cosmologists are “often in error but never in doubt”. The remark seems spot on. Still, disciplinary arrogance aside, On the Origin of Time lets you enjoy the cosmologists, understand their theories and realize their flaws, yet sympathize with those whose confidence will soon be demolished. The book even makes you look forward to their next ‘final’ theory.

Nature 616, 243-244 (2023)

doi: How Stephen Hawking flip-flopped on whether the Universe has a beginning

Addendum: Not criticizing. I just thought the connection to Arendt and the “view from nowhere” was interesting. Overall, I’m not a fan of postmodern criticisms of science, but that’s going by summaries I’ve read. I’m sure @glipsnort knows more about that subject.

It’s also the sole basis of why the real and natural numbers cannot be put in one to one correspondence.

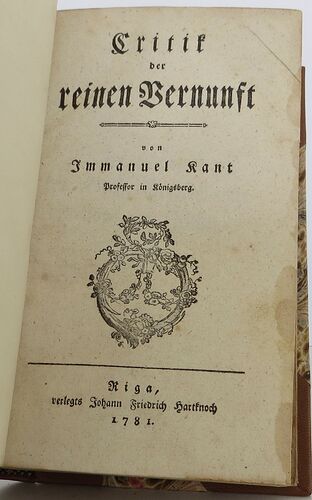

And while Kant recognized the law in his passage on the ontological argument, he did not consider it with respect to the possibility of nothing existing.

Sproul and Gerstner lay the credit for this version of the argument at the feet of Jonathan Edwards, who preceded Kant by a generation. Which then raises a curious historical possibility of Kant writing about the argument and how it proves an eternal necessary being, but still doesn’t prove God.

It would have been something if Kant got that. And how different the 20th century would have been. Or how different would have postmodernism been if the CPR showed what reason can and cannot prove?

For the philosophically illiterate among us and especially those with senior memory to boot, initialisms and acronyms need to be spelled out: CPR. ![]()

(“disa” is a Text Replacement [aka keyboard shortcut] alternative on my iPad to spelling out the whole word “disambiguation” – I use it quite a lot. ; - )

(The last entry on the Wikipedia page was more than a hint. ; - )

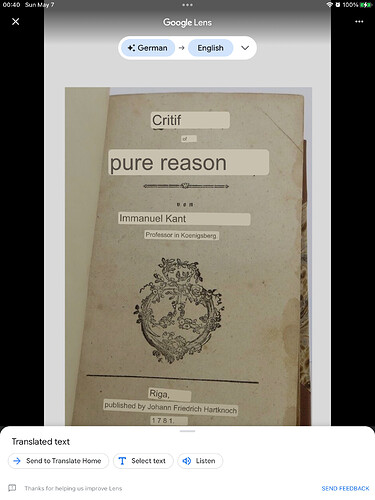

And then there’s Google Translate…

It couldn’t quite make out the old German calligraphic flourishes on the first word though.

I’m fascinated just sitting here looking at the image and knowing that Kant had a Hamann. I don’t know if you saw the comments, but credit for the term metacritical goes to Hamann and not the postmodernists, he may well have been the one to awaken Kant from his dogmatic slumber, and I see a good possibility he was Kierkegaard’s knight of faith.