In a way, you are correct. I do not doubt that God had/has intentionality/design in his governance of all in all. That being the case, there must be the intentionality of God/design of God everywhere. Including in abusive relationships, in the holocaust, in paint drying, in all suffering, in peanut butter, etc. But the God whose designs play out in all things is no comfort and. more importantly, no friend of the Christian (only the God who works all for the good of those in Christ Jesus Rom. 8:28). Recall Job’s friends who attempted to point out to him where and why the hand of God was in his life. Job agreed with them that God was involved in his circumstances. But he was right to differ in holding God accountable for all things, the point of the end of the book being that this God is beyond human comprehension; that his actions in the world are not comprehendible or accountable to human reason. The only respite is his promise to show himself right and merciful in the end.

It should likewise be noted that just because we acknowledge God as designing all in all does not mean we think it is humanly understandable. What humans may deem as evidence of design could, in all likelihood, be nothing akin to how God designs. And thus, could be more human vanity and folly. What we perceive and may rightly deem as random and chaotic and emergent (e.g., consciousness, traffic, weather, etc.) could easily fit into God’s governance as something he designs with a certainty only he understands. This God who governs all and incomprehensibly to us is more amiable to the Christian doctrine of God’s transcendence.

Thus, to deem God’s designs in creation as present but incomprehensible and to deem those who seek to discover such designs as attempting to be unduly self-righteous (I say this not in condescension or accusation, but it is literally an attempt to prove one’s self in the right before God/to prove God right) is more apt for Lutherans (though some in our camp do not realize the depth of this assertion). I quote at length from Bayer (Living by Faith, page 78) and Luther:

When we ignore this unconditionality [of faith in God’s kerygmatic and sacramental promise] and try to understand the order of the world through the “light of nature” or natural reason, we want to perceive a perspicuous nexus of acts and consequences. But we will be like the friends of Job, who according to Luther, “had human and worldly concepts of God and his righteousness, as though God were like us and his laws like those of the world.” No less appropriate than the views of these rationalists are those of the empiricists. Luther says:

If you respect and follow the judgment of human reason, you are bound to say either that there is no God, or that God is unjust… Look at the prosperity the wicked enjoy and the adversity the good endure, and note how both proverbs and that parent of proverbs, experience, testify that the bigger the scoundrel the greater his luck. “The tents of the ungodly are at peace,” says Job [12:6], and Psalm [73:12] complains that the sinners of the world increase in riches. Tell me, is it not in everyone’s judgment most unjust that the wicked should prosper and the good suffer? But that is the way of the world. Here even the greatest minds have stumbled and fallen, denying the existence of God and imagining that all things are moved at random by blind Chance or Fortune. So, for example, did the Epicureans and Pliny; while Aristotle, in order to preserve that Supreme Being of his from unhappiness, never lets him look at anything but himself, because he thinks it would be most unpleasant for him to see so much suffering and so many injustices. The prophets, however, who did believe in God, had more temptation to regard him as unjust – Jeremiah for instance, and Job, David, Asaph and others.’”

Lutherans align themselves with the prophets and confess that there is Divine design everywhere (Luther was particularly fond of peach stones and blades of grass). But some (in our camp and possibly including yourself) think it safer and more intellectually appealing to relegate some or even all of that design into a notion of “irreducible complexity” or other, humanly discernable evidences of “some-nondescript-one else’s” hand in creation. Regardless of the scientific arguments circling such evidences, the framework of relegation is theologically diminutive of God. Diminutive because God literally and at every point along the way, even in the means, works all (everything; no holds barred) in all. So if you think you can scientifically see a designer in the flagella, then you should be able to scientifically tell me where you see a divine designer in the atom bomb and the use of zyklon-B in gas chambers (you may say you see fallen humanity rather than the divine, but remember, it is God who governs all, including bird migrations and fallen humanity; while the bondage of the human will [either to the devil or to God] and the Deus absconditus may not sit well with the tastes of others, remember you are commenting here on Lutheran theology in particular and its reception of design, so these dogmas [e.g., the omnipotence of God over all creation, the bondage of the human will, etc.] must be taken into account).

I understand the impetus to seek out some evidences of God’s design in creation (as his is the only '“intelligence” I assume there would be in such things). But Christ came to end our attempts at finding a way, any way, to God, to influence God, and to know God. He did so by bringing God to us in the clearest (yet, ironically, most hidden) way possible. Lutherans have historically owned this dogged clinging to Christ and God’s revelation alone since the start (and Christians have been doing so since before Luther; e.g., Ockham).

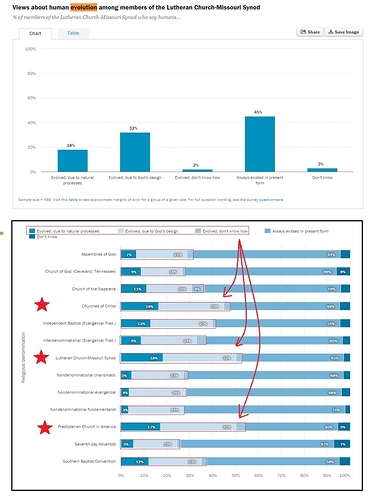

As a final note to this comment of yours about ID and hopeful possibilities: The design ascribed to by the LCMS’s CTCR (Commission on Theology and Church Relations), ascribed to by LCMS.org, ascribed to by our governing president (Matthew Harrison), ascribed to and affirmed officially at our synod and district conventions, is not amenable to EC. The LCMS is, officially, a proponent of 6, 24-hour days, Ken Hamm, young earth creationism. On the books, regardless of pew polls, we are opposed to the ID movement insofar as it affirms an old earth, “macro” evolution, anything other than a purely and strictly literalistic reading of Genesis 1-2, etc. I appreciate the optimism. I really do! And I appreciate the theological reasoning behind our official stance. The reality is, I think, a more difficult matter.