John Dominic Crossan has bad rap with evangelical Christians but in all truth he is a world renowned and pre-eminent scholar whose work is carefully argued and worthy of serious consideration. I have generally enjoyed his contribution to Christian history (e.g., The Birth of Christianity , The Historical Jesus , Jesus a Revolutionary Biography ) and given my belief in the accommodation of scripture and serious problems with its darker portions, his obviously provocative work, Jesus and the Violence of Scripture, How to Read the Bible and Still be a Christian, immediately caught my eye.

I’d like to offer some comments and points from the book and discuss the less congenial Jesus found in parts of scripture and the book of Revelation in particular. What is everyone’s thoughts about Christ the Conquerer in Revelation?

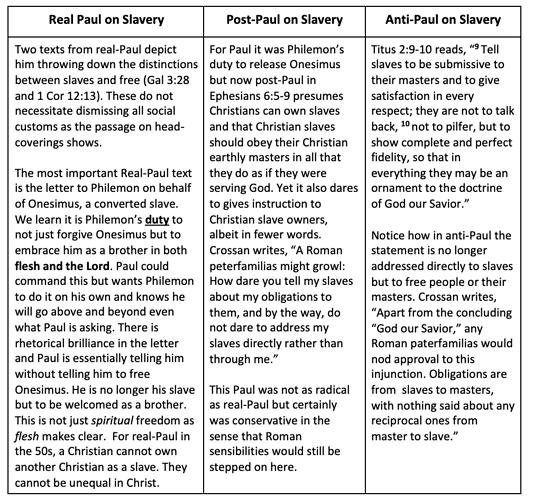

I see that he is also going to point out something many conservatives will not like: trajectories on slavery and misogyny inside the Christian canon. He sees serious difference on women and slavery in what he deems real-Paul (7 genuine epistles), post-Paul (3 epistles) and anti-Paul (pastorals). A review of chapter 1 with some of my own thoughts below:

Chapter one starts off with a bit of biography. Crossan explains his education, what caused his split from the Catholic faith (birth control) and hints at ultimately how he navigated faith and history throughout his career. He said he was a Christian before a historian so he is aware at the different lenses for viewing the Bible. He also speaks of a formative incident that had a lasting impact on him that occurred while watching a Passion play. There is a legend of surviving villagers ravaged during the Bubonic plague 400 years ago. In exchange for deaths to stop their end of the bargain was a passion play that was performed yearly from 1634-1680 and then in ten year increments ever since then. The passion includes the final portions of Jesus’s ministry as recorded in the Gospels from the triumphal entry to the empty tomb. Crossan includes a review of that play from none other than Adolf Hitler:

“It is vital that the Passion Play be continued at Oberammergau; for never has the menace of Jewry been so convincingly portrayed as in this presentation of what happened in the times of the Romans. There one sees in Pontius Pilate a Roman racially and intellectually so superior, that he stands out like a firm, clean rock in the middle of the whole muck and mire of Jewry.”

Anti-Semitism is something the modern church should strive to avoid but literal adherence to the Gospels does not always make that easy. The problem for Crossan was the sudden shirt in the Crowd during the passion. How Jesus could draw such a large crowd during the triumphal entry that was positive to him, how could his appeal be so great in the Temple the Jewish leaders were afraid to arrest him, but now the crowds and the Jews are adamantly demanding his crucifixion? The live version exacerbated the problem for him. It struck a chord. “How had the same crowd that filled the huge stage that morning to welcome Jesus on Palm Sunday become changed by afternoon to cry for his crucifixion on good Friday. It was for me a quiet but clear epiphany that something was missing from the story of Jesus’s passion, something was wrong when acclamation became condemnation without any explanation. ”[1]

The Matrix for Interpreting Jesus

Crossan puts forth a nonviolent reconstruction of Jesus and tells us that understanding a text in its proper historical context is essential. He calls its historical backdrop its “matrix.” For Martin Luther King Jr. the matrix is American racism, for Mahatma Gandhi it is British imperialism and for Jesus, “violent and nonviolent resistance to Roman power and imperial oppression.”

The Cleansing of the Temple

After he put forth his book on the Historical Jesus he found himself surprisingly invited to give talks at many churches on his vision of Jesus. Several issues always came up. The cleansing of the Temple and the book of Revelation. According to Crossan, the cleansing of the Temple was not a violent incident. Pope Francis agrees: “It certainly wasn’t a violent action. So true is this that it didn’t provoke the intervention of the guardians of public order – of the police. No!”[2] Some scholars think the lack of temple authorities stepping in is evidence of Jesus’s popularity which could mitigate this conclusion. What Crossan gets absolutely right is that historically speaking, Jesus was not considered a threat and therefore was not a violent person. If Jesus was a violent threat Pilate would have rounded up his closest associates and crucified them alongside him. That Jesus was crucified but none of his closest disciples were makes this all but indisputable.

As for the temple which some suggest depicts a violent Jesus, Crossan writes, “Jesus’s action in that case was a prophetic demonstration against worship in the Temple excusing injustice in the land—injustice exacerbated, of course, by necessary high-priestly collaboration with Roman imperial power and control. That is why Jesus quoted Jeremiah’s den of robbers” (Jer. 7:11; Mark 11:17). (Jesus was not accusing people of thievery in the Temple. A “den” is not the place for robbery and injustice inside, but the hideout from robbery and injustice outside.) Jesus was, in fulfillment of God’s threat in Jeremiah 7:14, symbolically “destroying the Temple by overturning its fiscal and sacrificial bases.” He also goes on to note that John makes it explicit that Jesus used a “whip of cords” to drive livestock out in a “religio-political demonstration.” He wasn’t using the whip on people. Crossan goes on to say that Mark emphasizes this nonviolence in contrasting Jesus with a violent and murderous Barabbas (15:6-9) and John 18:36 has Jesus explicitly state to Pilate his followers are nonviolent because his kingdom is not of this earth.

Crossan may be accused of taking the word den too literally but it is clear that neither Jesus during his lifetime nor his followers immediately after his death were opposed to temple worship. Quite the opposite in fact. John has a multi-year ministry and Jesus would have most likely went to Jerusalem during Passover many times to worship at the temple. He instructs a healed person to go and make the appropriate sacrifices in the temple. After his crucifixion, we can glean from Paul and Acts that some of his followers took up shop in Jerusalem, maintained temple worship and purity regulations in addition to observing Jewish festivals. Jesus and his immediate followers even after his death did not stop engaging in the temple’s cultic practices.

A thorny issue pops up immediately here if we view Jesus as cleansing the temple of corruption. In Mark, our earliest account of this incident, Jesus drives everyone out–the corrupt sellers and even the buyers who are being swindled. The buyers did nothing wrong. Why were they targeted? Matthew who copied Mark retains this but Luke omits this part and has Jesus only driving out the sellers which makes more sense in a “cleansing.” In John, where the temple incident comes chronologically much earlier in his ministry, Jesus is reported as only driving out the vendors and the livestock.

Another problem here is that commerce was a vital part of temple worship. People traveled great distances to the Temple and it was scarcely feasible for them to bring their own animals to sacrifice, especially if they were to be unblemished. How were people from different lands expected to have the proper coinage? Money changers were vital to proper temple worship. Paula Fredriksen asks of this incident, “Were pilgrims coming in from Egypt or Italy or Babylon supposed to carry their own birds with them? pick them up anywhere? have their own supply of Tyrian coinage, or hope they would get some somehow during their trip?”[3] Commerce in the Temple had existed for a very long time. It might be argued Jesus wanted the selling done outside the Temple but this is a highly nuanced and troubling issue. At least since the time of Solomon this commerce was occurring and the point of the Temple or generally any temple in antiquity was a place to make offerings and worship God. It makes sense to obtain your animals and necessary coinage there. Fredriksen writes, “Pigeon vendors and money changers, in other words, facilitated the pilgrims’ worship of God as he had commanded Israel through Moses as Sinai. Jesus’ gesture therefore could not have encoded “restoring” Temple services to some supposed pristine ideal, because there had never been a time when its service did not involve offerings.”

As we can see from Jewish writings including Apocrypha and the Dead Sea scrolls, there was an expectation by some that God would destroy the temple and rebuild a better one (see the accusation in Mark 14:58). This is not a cleansing per se. Jesus is not telling his followers to avoid a corrupt temple and that is why they did not after his death. In Mark the scene is a prophetic gesture depicting the expected destruction of the temple by God. The withering of the fig tree which represents the temple makes this all too clear. The fig tree was not cleansed. It was destroyed. Completely destroyed ( withered from the roots ) even as the temple was razed and torn down piece by piece.

The temple had its own security and during festivals like Passover, the number of Roman soldiers in the area was beefed up as well precisely to quell such disturbances. Oddly, both of these parties are largely silent and inoculated here while Jesus performs this action, the same rock star Jesus who just entered Jerusalem in a crowd as a king during Passover, their penultimate liberation festival! Viewing this as a limited and non-violent prophetic gesture on a smaller scale where Jesus predicts God’s eschatological judgment on the temple and possibly it subsequent destruction makes more sense in historical context. It is possible all four evangelists write after the destruction of the Temple and a legitimate prophetic gesture by Jesus condemning Temple practices were turned into an ex eventu prophecy about its destruction as well. The Gospels do not permit a high degree of certainty here, only that Jesus was displeased by something happening in the temple and enacted a prophetic demonstration of of what is found in Jeremiah against it.

Crossan considers the Temple cleansing the easier of the objections against a nonviolent Jesus to answer. The book of Revelation with its gory details is another matter. Those who think Divine violence is really just a problem in the Old Testament clearly haven’t read the entire Christian corpus. A very strong argument could be made that Revelation is the worst of the worst in this regard. Crossan tells us the good-cop New Testament and bad-cop Old Testament doesn’t work for those of us who have read all of the Bible and that is an anti-Judaism, Christian stereotype. Ananias and Sapphira might be able to tell us more about it.

Rev 14:19-20: 19 So the angel swung his sickle over the earth and gathered the vintage of the earth, and he threw it into the great wine press of the wrath of God. 20 And the wine press was trodden outside the city, and blood flowed from the wine press, as high as a horse’s bridle, for a distance of about two hundred miles.

The book of Revelation is violent and if taken lierally, on a scale far outweighing all the violence in the Old Testament combined. The biggest concern is the same Jesus who tells us the parable of the good Samaritan, that God sends his rain on the just and unjust, that we should turn the other cheek, to love our enemies, that whoever lives by the sword shall die by it and for Peter to put his sword away, is going to bring forth epic violence, death and destruction in the end. He unleashes the four horsemen. In Revelation 19 the nonviolent and sacrificial lamb of God becomes Christ the Conqueror. Fortunately, none of these metaphors appear to be truthful. Revelation is largely concerned with Rome and gets much of it wrong if we read it concordantly. Crossan considers it “profoundly wrong” about Rome:

[1] Rome’s destruction was said to happen soon and climax with the second coming (Rev 1:1, 2:16, 3:11, 11:14, 22:6-7, 22:20), but as Crossan writes “the Western Roman Empire continued until the 400s and the Eastern until the mid-1400s.”

[2] Roma was converted to Christ after Constantine’s conversion in the 300s, not destroyed by him. Crossan notes, “Only Luke-Acts imagined the future correctly as Roman Christianity.”

[3] Clearly the destruction of Rome was not a “consummation of the world, the establishment of a new heaven and a new Earth in that wedding feast of divinity and humanity (21:1-5). That heavenly vision is still a consummation devoutly to be wished and very far from clearly imminent.”

My fellow Christians who read Revelation and profess Biblical inspiration may want to take a cue from John Walton’s playbook in regards to the primeval history in Genesis. Revelation was written for us but not to us. Any purpose or meaning we glean from Revelation should be tied into whatever issues its audience was facing at the time of its composition. In all likelihood, the destruction of the Temple was part of that backdrop. In other words, to us its less about the future and more about past . To its original audience it was about the present .

A part of the chapter I found fascinating is how the violent vision of Jesus in Revelation was amplified by the Left Behind and the Narnia series in recent times. The Left Behind “books and their subsequent movies and games, arranged multiple and discreet Biblical images of cosmic consummation into a more or less coherent scenario. But in doing so they made one egregious expansion beyond even Revelation’s divine violence. The great final battle was to involve not just Christ and the angels, as in Revelation, hut humans as well.”

In the second to last book of the Left Behind series, the protagonist Mac who had been converted to Christ sprays his uzi outside Jerusalem’s Damascus gate at over a dozen GC from behind. “He felt no remorse. All’s fair . . . It was only fitting, he decided, that the devil’s crew were dressed in black. Live by the sword, die by the sword .” Crossan writes, “Notice how the authors (ab)use the warning of Jesus that “all who take the sword shall perish by the sword” (Matt. 26:52). Jesus said “all,” but Mac lacks any sense of self-criticism—or even the grace of irony. “

In Narnia, four children also partake in the final battle. For those familiar with the tale, Peter kills the wolf-monster and Aslan, the Lion who represents Christ, tells hm “You have forgotten to clean your sword . . . whatever happens, never forget to wipe your sword.” Crossan’s response to this is, “I have to recall a different admonition to another sword-yielding Peter: “Put your sword back into its place, for all who take the sword will perish by the sword” (Matthew 26:52).”

Crossan in giving talks in churches about the nonviolence of Jesus writes of Left Behind and Narnia, “Both of those series generated questions and objections from my lecture audiences when I spoke of Jesus’s nonviolent resistance to Rome’s control of his first-century Jewish homeland. If I wanted to speak, as I did, about the historical Jesus, my audience asked, as they should, about Revelation and its divine violence now at least fictionally supported by human violence.”

Crossan ends the chapter noting “bipolar” visions of God in scripture that he bifurcates as follows: “the Biblical God is, on one hand, is a God of nonviolent distributive justice and, on the other hand, a God of violent retributive justice. How do we make sense of this dual focus? How do we reconcile these two visions? . . . Do we choose to follow one or the other option since both are presented as the character of the Biblical God?"

[1] Crossan, Jesus and the Violence of Scripture, Page 5

[2] Article by Pope Francis, Jesus Cleanses the Temple.

[3] Paula Fredriksen, Jesus of Nazareth p 269)