Hi Brad

It’s hard to know where to start on this, because one could write a book about it. In fact I have!

Since I’m replying to your thinking process rather than the finished piece, please excuse my taking up disparate points, which I hope may help rather than hinder your thinking.

First, I’m very pleased you start with David Bentley Hart, because one of his strongest, and most provocative, points (from Aquinas, actually) is to challenge the idea that God is “a moral being”, to be judged according to our sense of justice or even by the Law he gave us. Hart is cited in a new article to which Ian Thompson alerted me at The Hump. Although its focus is on animal suffering, much of what Aquinas says can be applied to natural disasters, so I think the way he turns our thinking on its head can be very valuable in this topic. It deals pretty well with the “a loving God wouldn’t cause suffering” argument that is, basically, Leibniz theodicy heated over.

Second, there is an obstacle to be overcome for a good many ECs, who have not in any way come to terms with a truly theistic concept of God involved with nature in terms of evolution, and still less with the daily operation of the world. This semi-deism contrasts not only with Gen. and Rev., but with the whole Bible, and it is exemplified by the way that on threads at BL, the weather has been taken as a gold standard of “natural autonomy” by which other phenomena are assessed. Yet God’s control of the weather is axiomatic in Scripture - to the point that in parts of the OT he’s almost like a storm God, riding on the clouds and speaking through thunder - images continued even in the NT.

It’s going to be hard, in your article, to get on to why God might bring, or allow, natural disasters before getting beyond the tired Deistic idea that science has shown “they just happen” because God set up the laws and can’t interfere - I say Deistic, because one of the early triggers for rationalist Deism proper was the Lisbon earthquake of 1755 - the King of Portugal called a Day of Humble Prayer - the rationalists responded by distancing God from nature.

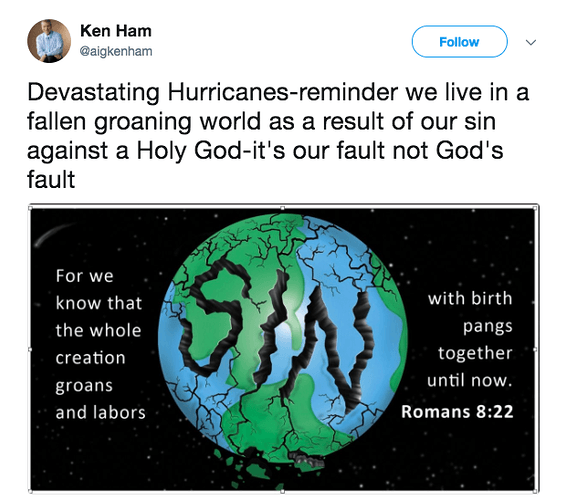

Thirdly, Ken Ham’s “traditional” blaming of natural disturbances on the Fall is not only unbiblical, but historically recent as theology. That’s what prompted me to write my book God’s Good Earth. On the other hand, the control of God over nature, moment by moment, is linked to both blessing and judgement throughout the Bible. Most notably, the covenant blessings and curses which were an integral aspect of the foundation covenant of Israel under Moses, both prospectively and retrospectively, largely invove the natural world - weather, soil fertility, health, wild animals (and what isn’t nature is God’s control of potential human enemies).

Thus faithfulness to the covenant would bring for Israel spring rains, abundant crops, few wild beasts, many children, good health and peace: whereas disobedience would bring drought, hail, locusts, famine, plagues and invasion by foreigners. The later prophets interpret Israel’s history pretty much entirely through the lens of those covenant consequences, up to and including the exiles of Israel to Assyria and Judah to Babylon - which exile events govern the whole of subsequent salvation history up to, and including, the coming of the Lord Jesus (see N T Wright on this).

Fourth the last point impacts hugely on understanding Revelation. As it happens I’m teaching Revelation to a home group currently (I think the fourth or fifth time I’ve taught it in depth). It’s no coincidence that much of the “scary imagery” that puts people off the book is directly derived from those Mosaic blessings and curses. There’s somewhat to say about how those are developed. In the “7 seals” series, they’re presented as part of the mystery of God, things that “have to happen” before the end, without piercing God’s mind to know why, other than that it’s the future made possible by the victory of Jesus on the Cross (and so presumably also part of the remedy for the sin that made that necessary). In the “7 trumpets” series, they are presented as warnings to sinful mankind, and moreover are linked to a general failure to repent - much as they are with respect to Israel in the prophets. In both cases, they are clearly presented as of God’s direct authorship, leading me to sketch a biblical theology of nature for you to play with…

Fifth it seems to me that Scripture uniformly presents nature (as you rightly say, including even the symbolically chaotic elements such as sea) not as an autonomous realm over against God, but as an instrument, or agent, which serves his purposes (whatever they may be) obediently. That’s why it cuts directly across the versions of Evolutionary Creation that stress nature’s “freedom” etc. The Levitical and Deuteronomic blessings and curses exemplify this - the same nature is used to bless or judge Israel in response to “events on the ground”, but always in obedience to God’s inscrutable wisdom.

For God to send Joel’s locusts or the Babylonian army does bear a fairly simple correspondence to national sin. But both in the OT, and par excellence in Revelation, the more sophisticated realisation that God’s governance of the entire world, respecting the “just deserts” of each individual human, let alone each sparrow that falls to the ground, are not to be reduced to crass simplifications like “there was an earthquake, ergo it’s because of Trump/Gays (etc)”. If you want an instance of how that divine sublety plays out, check out the Armenian earthquake of 1988, of which I heard an Orthodox priest at the time say on BBC news (deistically) “Sometimes God isn’t there - things just happen.” Yet now, the earthquake is widely regarded there as the catalyst for both national and spiritual revival there. Not many Ken Hams would have predicted that, nor would semi-deists credit it, but a prophet might have!

The absence of sea in Revelation is, as you rightly say, an apocalyptic representation of the absence of chaos, tohu wabohu, rather than of oceans, in the new creation, and so is a direct allusion to the Genesis 1 creation and the tehom. Incidentally, sea and the Abyss are synonymous in Rev., and “abyss” in the Septuagint is used for tehom, so “no more sea” is the culmination of a theme. (Also incidentally, the presence of sea before God’s throne in ch4 is not incompatible, even in visionary terms, because it refers to the imagery of the bronze laver, or “sea”, in Solomon’s temple, only made of crystal to give added whiteness to God’s heavenly priests!)

Sixth and last (for no good reason other than having waffled on enough and having work to do!) the gleanings from the Biblical worldview above, although they prevent us taking any old natural phenomenon and tying it to a sin of our choosing, nevertheless alert us to seeing God’s moral governance of the world in our Christian response to natural disasters. I mentioned the response of believers to the Lisbon earthquake - a national day of repentance and self-examination in the light of God’s visitation. They took Amos 3.6 seriously: “Does disaster come to a city, unless the LORD has done it?”

The same happened in England immediately after the Fire of London - the process was not so much soapbox orators using the disaster to highlight their favourite complaints, but God’s people, recognising God’s unusual allowing such a thing, examining their national conscience and praying for renewal, in the knowledge that the doings of God should not be divorced from the doings of his servant, the natural creation.

One might think about how that could apply to global warming: if it’s anthropogenic, then human irresponsibility and greed are the sins responsible, and maybe as well as the Paris Accords there is a place for humble confession - and (if we are theists rather than deists) also pleas that God might mitigate it. If it isn’t anthropogenic, then (according to Scriptural theology) it’s not independent of God’s government, and we ought still to be, as Christ’s Church, examining ourselves and calling on his mercy.

Blessings to you

Jon