Genesis begins with Adam and his immediate family, Cain and Seth, without any time or place identifiers. Exegetes have speculated for centuries and the Garden of Eden has moved all over the globe. Genesis 1-3 has been analyzed and pontificated upon by numerous authors in recent years as if that’s all we needed to know that was important. And yet just one chapter farther lies a bit of “smoking gun” evidence that has been totally overlooked.

Genesis 4:17: “And Cain knew his wife; and she conceived, and bare Enoch: and he builded a city, and called the name of the city, after the name of his son, Enoch.”

Don’t concentrate on the “land of Nod” or the act of conception. Cain’s son was named “Enoch,” and the city bears his name. In both Akkadian and Sumerian the En- prefix denotes a king or ruler. Just this fact alone pins down both the approximate time and the place! Thus, Enoch became king in the city Cain built in Mesopotamia located about 50 miles north of Eridu, the first city.

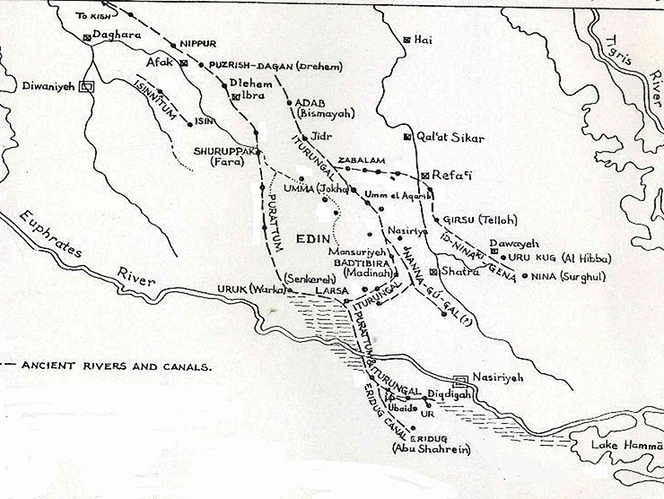

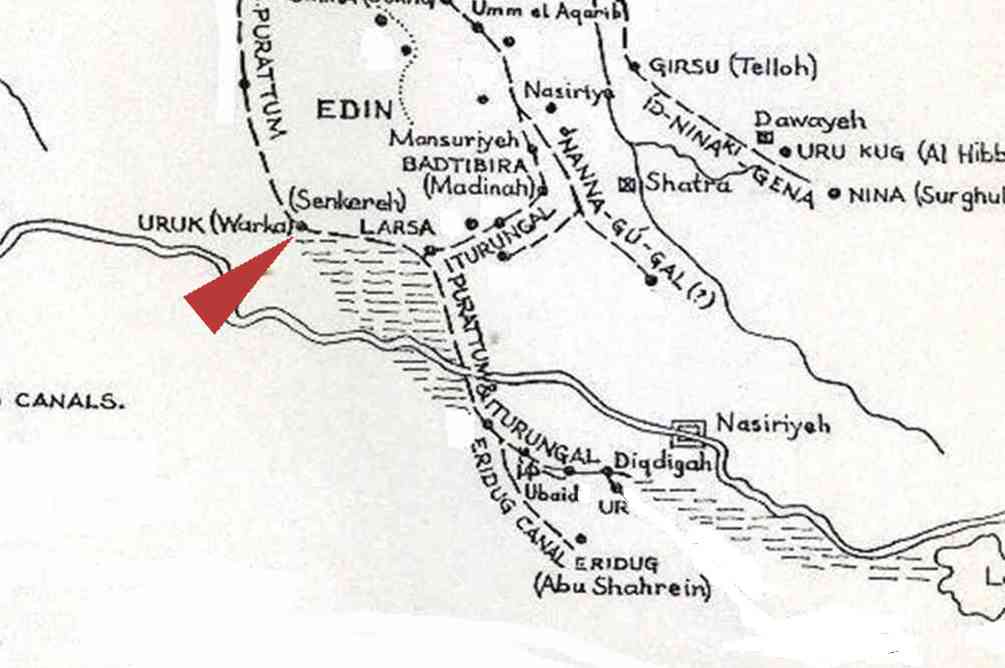

All Cain needed to do upon his banishment from the Garden was follow the Purruttum&Eridu canal either by boat or overland to an established settlement (probably Ubaidan), move in, take a wife, and have a son who became their king.

In addition to Cain’s son becoming king in the city of Enoch, Seth’s son, Enosh, also was king judging by the En- Prefix. Determining where his kingdom was located requires a bit of sleuthing. The Sumerian King List gives a clue. After the first two kings reigned at Eridu, “Eridu was smitten with weapons and kingship was carried to Bad Tabira.”

Initially a Sumerian city, judging by the names of the kings who are listed, this was the first recorded war in human history. It was between the Sumerians at Bad Tabira and the Akkadians who lived at Eridu. Seth’s kin were either driven out or were called out and journeyed along the same path their cousins did and established their city alongside apparently recognizing there was safety in numbers. Support for this scenario comes from the SKL and from a Sumerian legend.

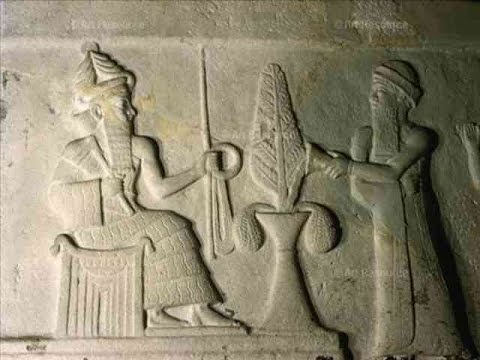

In the Sumerian King List after the flood Enmerkar, a Sumerian, rebuilt Enoch, “ Unug ” in Sumerian. In the legend Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta (biblical Ararat), the king describes the city as a “majestic bull bearing vigour and great awesome splendour." In his account Enmerkar repeatedly used the phrase, Unug Kullaba , “Enoch the twin city1

- Translation courtesy of the University of Pennsylvania Museum

Accordingly Adam’s two grandsons were kings in their respective adjacent cities, Enoch and Erech, Unug and Uruk in Sumerian. Today the entire united city is called “Warka” in Iraq and lies about 50 miles north of modern “Abu Shahrein” as you go along the Purrattum&Eridug canal.

Map shows Enoch, the city Cain built although a settlement had already been established before he arrived, likely Ubaidan. After Eridu was attacked we surmise Adam’s other grandson took the same path and with his family established a twin city. One clue that bolsters that conclusion is that their subsequent children had similar names and even identical names in one instance. This indicates close contact. Another clue is the recorded account of Cain’s children in Gen. 4:18-24. Had Cain simply disappeared altogether how would the author of Genesis have obtained this information? As twin cities the fortress walls that were installed prevented any successful attacks, at least none were recorded.

The Sumerian King List(s) have been the subject of debate since the first tablets were discovered in excavated Mesopotamian cities. They contain both pre-flood and post-flood kings. All are inscribed in Sumerian and include Sumerian names even though many of the listed kings appear to have been Akkadian. Tablets discovered list from seven to ten kings in the section beginning with a time when “kingship descended from on high” in Eridu until “the flood swept thereover” and kingship had been in Shuruppak where the ark was built according to legend. At least three kings and possibly four do appear to be the last four pre-flood biblical patriarchs named in Genesis Five including Noah, named Ziusudra (he who found long life) in the SKL. The complete rationale is contained in a YouTube video, “Genesis Five and the Sumerian King List.”

When Stephen Langdon translated the Sumerian king list into English he encountered the Sumerian unug as the second city reconstructed after the flood following Kish. Had he been faithful to the text he would have translated it as “Enoch.” Instead what we read in English in Langdon’s translation is “Erech,” the Sumerian uruk . Why did he do that? Surely he would have been asked if this was the same city Cain built! How would he have answered? Did Langdon believe the city of Enoch couldn’t have survived the flood? Did he wish to avoid almost certain controversy? After all, how could a respected curator of archaeology and anthropology at the University of Pennsylvania go about lending his endorsement to Bible trivia? Or perhaps he recognized that Enoch and Erech were either at the same place or they were the same place, and what difference would it make? Alas, his motives will forever remain unknown.

Noah himself, or his son Shem, would be the probable source of the knowledge of pre-flood persons and events passed down and preserved by the Semites. Shem would have learned the chronology of his family line back to Seth and Adam from his father, or his grandfather, Lamech, or his great grandfather, Methuselah. Yet the history of Cain’s progeny had to have been provided through some other source, likely someone in Cain’s line. At what point or by whom the histories of Cain and Seth were packaged into one document is impossible to know. Take note of the differences between the two accounts. Cain’s line is richly documented while Seth’s line is a tedious litany of begats. It is apparent that communication took place between families. A reunification of the two family lines at Enoch/Erech provides an obvious answer.

The rationale for a cleansing flood is outlined in Genesis 6:5-7. God singles out for destruction those deserving to die. The word for “man” in these consecutive verses is ‘adam.

Gen. 6:5: "And God saw that the wickedness of man [ ‘adam ] was great …”

Who were wicked? Those from Adam.

Gen. 6:6: “And it repented the Lord that he had made man [ ‘adam ] …”

It was not generic mankind or even the nearby Sumerians who grieved the Lord, but those from Adam.

Gen. 6:7: “And the Lord said, I will destroy man [ ‘adam ] …”

And those emanating from Adam met destruction.

Genesis does not give us reasons for the wickedness that pervaded God’s chosen race. There are clues, however, imbedded in the history of the two cultures living in close contact in southern Mesopotamia, the Akkadians and the Sumerians. Initially, the Akkadians worshipped three gods with roles that closely resemble our Trinity. On the other hand, the Sumerians worshipped over 3,000 gods that presided over every walk of life. Idols and images of these gods abounded. Over time the impressionable Akkadians became corrupted by their Sumerian neighbors and embraced many of their gods. The Sumerian sun god, “Utu,” was the Akkadian, “Shamash.” The Sumerian fertility goddess, Inanna, became the Akkadian. “Ishtar.” And so on.

Whatever else we may know about God we should know that worshipping false gods and idols gets him really upset. The flood ensued as judgment on those who were accountable and should have known better. The Euphrates basin bore the brunt of the flood where the Akkadians were concentrated. Located more to the east, the Sumerians suffered collateral damage but survived to rebuild cities destroyed by the flood as documented by the Sumerian King List.

In 1928-29, Leonard Woolley excavated the ancient city of Ur in southern Mesopotamia. It had once been a thriving Sumerian port city on the Persian Gulf. The build-up of silt over centuries moved the coastline south, and by then the long-abandoned ancient ruins were buried many miles inland. “The graves of the kings of Ur," Woolley called them, yielded their treasures of precious trinkets one by one. Cups and goblets, vases and jugs, lyres and harps, gold, bronze, and silver pieces of adornment were excised from rooms lined by walls of stone. Grisly skeletons were wrested from their dark resting places and brought to searing sunlight.

In the summer of 1929, toward the end of their season, Woolley’s native digging crews made one last probe to see what was in store for the following year. They found more artifacts beneath the lowest tomb. Encouraged by these finds, Woolley wanted to know how far down they had to go before the treasure trove would end. Shafts were sunk carefully. Sand and debris were brought up for examination. Woolley dated the lowest tomb to 2800 BC. Now, bucket by bucket, he was traveling back in time.

Clay tablets started appearing among the loose debris. The inscriptions bore characters even older than his previous finds. He had reached 3000 BC by his reckoning, and with appetites whetted afresh, still there was more to come. Shafts were sent down deeper still. At last the floor was reached and they stood at the bottom - or so they thought. Then Woolley noticed the soil had changed from sand to clay. Upon close examination, Woolley determined the clay had once been dissolved. What was water-laid clay doing in the middle of a desert beneath these tombs?

Woolley’s first thoughts were that a clay layer must have been set down when the Euphrates River overflowed its banks long before civilization had begun. Yet, the elevation seemed too high for that. His next step was to measure the depth of the layer of clay. To his amazement, nearly 10 feet of clay was discovered before reaching another level of civilization.

Once again artifacts were brought to the surface for scrutiny. Another discovery was made; the bits and pieces of pottery were uneven, a sign that they were made by human hands alone, unaided by the potter’s wheel. These painted potsherds were from a civilization even more primitive than the ones he had already uncovered. Woolley reasoned that two dissimilar civilizations separated by 10 feet of water-laid clay could mean only one thing. An ecstatic Woolley reached a conclusion and sent a telegram that electrified the world of 1929, “We have found the Flood.”