Although many proposals have been put forth to reconcile or at least accommodate the early chapters of Genesis alongside the revelations of modern science, the history of the ancient Near East largely has been ignored. Theologians for the most part have taken either a conservative approach, considering a traditional interpretation of sacred Scripture to be the final arbiter of all truth, or they fall into the scientifically astute liberal camp and feel it is necessary to relegate Genesis to some condescending category such as allegory, or poetry, or a theologically laden genre that was not intended to be taken literally.

For over 2,000 years exegetes have tripped over stumbling stones trying to make sense of Genesis. It is only within the last 160 years that archaeological findings and literature from Egypt and Mesopotamia, where clay tablets were inscribed in cuneiform style in both Akkadian and Sumerian, where we can conclude with reasonable assurance that Genesis has respectability as the legitimate history of the Semitic peoples.

The beginning chapters of Genesis have proved to be extremely difficult for theologians to comprehend. Should Genesis 2-11 be considered (1) “pre-history” or “proto-history” with theological intentions; (2) an accurate description of the beginning of the entire human race; or (3) an abbreviated narrative of the start of the Semitic race, Adamites, Semites, Israelites, Arabs and Jews?

If popularity was the deciding factor in determining what we should believe then the first two options would be clear winners, however, in science corroborating evidence normally wins out in the long run. With that in mind let’s explore some historical evidence that could tip the scale in favor of the third method of understanding. Even a “smoking gun” kind of evidence has come to light that ought to put the first two methods out of contention – in 200 to 300 years!

What are Adamites?

Historians use the term “Semites” to refer to the entire people group that speak a Semitic language, however, Shem was a post-flood figure. There is no term in use that defines those who lived in the pre-flood period, some of whom are named in Genesis. So I use the term “Adamites” to refer to those who would have been directly related to Adam to Noah. The only term in use by historians is “Semitic Akkadians,” but historians generally do not recognize biblical characters.

I know of none that could. They are mutually exclusive.

Let’s try this question about Semitic historicity with you as the test audience:

If we look at Exodus 13:17 (I used the Revised Standard Version here), we read:

"When Pharaoh let the people go, God did not lead them by way of the land of the Philistines, although that was near; for God said, “Lest the people repent when they see war, and return to Egypt.”

Archaeology tells us that the Philistines had entrenched themselves along the southern coast of the Levant by 1130 BCE. In fact, the only reason the Hebrew were able to avoid Egyptian hegemony

in the Sinai is that the Philistines had become strong enough to deny Egypt’s access to the Sinai as

well as to their former NORTHERN BORDER in northern Syria!

This contradicts the Genesis texts that say the Hebrew socialized with the Philistines 800 years before

they had even arrived in the southern coasts of the Levant.

Do you accept that the history of the Hebrew has been “inflated” by 800 years, with the Exodus

happening more recently than 1130 BCE, rather than sometime in the 1400s (Amarna period)?

Hi George, did you have a question about the first eleven chapters of Genesis? There are some who prefer a 1290 BC date for the Exodus. Genesis 2-11 covers about 2800 years from Adam to Abraham, whereas there are only about 2000 years from Abraham to Christ. Hardly anyone (actually, no one) has focused attention on these early formative years for our Christian religion. And that is a shame because it is an interesting historical period. I’ll try to fill you in on some of the history no one is talking about.

I am a Unitarian Universalist. So for me it is no stretch of the imagination that Genesis 1 to 11 was put together by taking various pagan writings … and giving them a nice Yawistic gloss! I feel the same about the Book of Judges. For example, the spelling and the story line tells me that Samson is a pagan story about a Sun god who has adventures in human form. Samson being BLINDED is pretty much an allegory for Samson being “eclipsed” … or blind and without power. But HAIR is also an allegory for Sun light … and so as Samson’s hair re-grows, his solar powers are restored.

Judges 1:8,10 seems to be a primitive INTRODUCTION to what will eventually become the Samuel narratives:

TOOLS

Jdg 1:8

“And the men of Judah fought against Jerusalem, and took it, and smote it with the edge of the sword, and set the city on fire.”

Jdg 1:10

“And Judah went against the Canaanites who dwelt in Hebron (now the name of Hebron was formerly Kir’iath-ar’ba”

In verse 8, we read that Jerusalem is captured… but the next time we hear about Jerusalem, it has to be captured yet again! The same with Hebron.

Even the books of Samuel have problems with the timeline. Supposedly the Levites lose the Ark of the Covenant to the Philistines… but before the year is out the Philistines have sent it back to the Hebrew. And what happens then? It’s totally bizarre - - David’s Levites don’t seem to know anything about how to handle the Ark. It kills the Hebrew just as it kills the Philistines. A good argument can be made that Samuel is actually the FIRST EVER of the narrations that deal with the Ark of the Covenant … and that when Exodus is written, it is the BACK STORY to the Books of Samuel that are the start of the histories.

In my view, the patriarchal section of the Book of Genesis is actually an ADDITIONAL back story to explain things that weren’t explained in Exodus. So Genesis becomes the YOUNGEST book … with stories and a timeline that are intentionally OLDER than Exodus or Samuel.

Hi George:

An interesting observation. I’d be interested to hear how Genesis was the YOUNGEST book. There are a few passages that do reflect on the prevailing culture in Mesopotamia during the period 4800 BC to 2000 BC that would be difficult to know about during the Babylonian captivity in my estimation. One example is the mention of the “fountains of the great deep” (Gen. 7:11). In Akkadian and Sumerian literature “fountains” pertain to their irrigation systems and the “deep” is any body of water including irrigation canals. So the Genesis flood demolished the dikes. levies and water wheels they used to bring water to their fields of crops. We can know that today due to the recovery of many pieces of literature in recent years, but it is doubtful this would have been known1400 years after Sumer was destroyed.

~Dick

A thousand years ago I wouldn’t be surprised if Genesis STILL reflected cultural reality somewhere in the middle east.

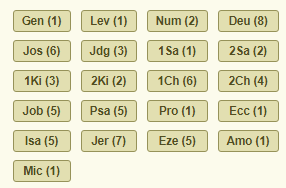

In my view, Genesis reflects Persian contexts, as well as the realities of the Iron Age. The Hebrew word “barzel” (Strong’s H1270) means IRON. While iron was known in the bronze age, it was relatively rare and expensive. Here is a listing of word frequency in the various books:

In Genesis 4 we read about an artificer in iron - - which seems incongruous. Deuteronomy, which covers the same bronze age as Exodus and Leviticus and Numbers and Joshua… we find iron is referenced 8 different times - - and for all these books a total of 20 times!

As for your interpretation of the “fountains of the great deep”…

I think you have missed the point completely. The water that flooded the Earth comes from “the Deep” … the Apsu … or Abzu … and this interpretation of the world comes directly from the Akkadian contact with Sumer… ultimately to be promulgated by the Assyrian and Babylonian successors of the Sumerians and Akkadians.

And then there are the scientists who have become Christians and taken up theology with a foot in both worlds. They, as I have, might see (after taking out your subjective use of the word “condescending”) see these two categories as entirely compatible. Science works in a particular way according to some methodological ideals and one can take up that work without adopting the premise of naturalism that this defines the limits of reality. I believe in the spiritual aspect to reality precisely because I don’t think the objective methodology of science captures the totality of reality.

But while the reactionary theologian who takes up an opposition to science might put his own work up as equally or more objective, those such as I see this as very foolish and doomed to failure. Instead of trying to be a competitor for science, the theologian should be taking up a different task entirely to uphold the undeniable reality that objective observation alone (where what we want and believe is irrelevant) is entirely inadequate for life, for life undeniably requires subjective participation (where what we want and believe is crucial).

Those truly understanding of the methodology of science know its limitations. It can only speak of things according to the objective evidence, and the objective evidence about the past is almost entirely restricted to the large scale events, while the Bible is pretty much focused on individuals and fairly obscure nations. Instead of this sullen reaction to the labels of allegory and poetry (to which I would add the label of “myth”), I would suggest that this is a doorway into this other highly needed aspect of life having to do with the subjective participation. Instead of insisting on some kind of delusional objectivity, we should be embracing its subjectivity, knowing that this is connecting us to what we must know by faith in things unseen (not proven) but hoped for.

Point well taken. But as you know, compatibility comes at a price. And the reliability of the biblical text takes the hits.

The god Enlil traversed the deep, and that was the Purratum Eridu(g) canal that went initially from Eridu (modern Abu Sharein) to Uruk (modern Warka).

Mesopotamian scribes were responsible for copying edicts of the king for dissemination. In addition to their routine tasks they also wrote and copied stories about gods and kings. The most popular among these is the Legend of Gilgamesh written in twelve tablets. Historical Gilgamesh was the fifth Sumerian king of Uruk (biblical Erech), in the post-flood era around 2700 BC. Only one tablet, the eleventh, is inscribed in Akkadian that describes an encounter between the famous king and the equally famous survivor of a massive flood, Utnapishtim (he who found long life), who we would recognize as Noah. The rest of the twelve tablets are in Sumerian and describe fantastical feats that may have some historical merit, but most probably were concocted by imaginative scribes. The point here is that kings who actually lived and gods that didn’t were popular subjects and stories about them were freely embellished.

There are a number of famous legends and epic tales that sprang from the fertile minds of Mesopotamian scribes. Besides the twelve tablets of Gilgamesh, citizens could read the romantic adventures of King Dumuzi and the goddess Inanna, Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta (Urartu, biblical Ararat). Tales of Akkadian gods Enki, Enlil and Babylonian god Marduk have been recovered. What these stories have in common is that the subjects are either deities, male or female, or kings. We can assume the public’s attention was drawn to these two categories of characters almost to the exclusion of any other, almost that is, because of one notable exception. This man was neither god nor king. He was a priest living in Eridu, the first city built in southern Mesopotamia and his name as translated comes to us as “Adapa.”

Several fragments of the legend were taken from the Library of Ashurbanipal at Nineveh. One also was found among the Amarna tablets in the Egyptian archives of Amenophis III and IV dated to the fourteenth century BC.1 To date, six fragments of the Adapa legend have been discovered written in various Semitic languages.2 Versions and fragments of the Adapa myth have been found in Akkadian, Canaanitish-Babylonian, Assyrian and Amorite.3 Even a Sumerian version similar to the Akkadian legend was discovered at Tell Haddad in Syria.4 Of note is that versions were recorded in languages tied to tribes on different branches of Noah’s family tree. Who would have been important enough or so well known that descendants of both Ham and Shem would have written about him?

Notes

-

Albert T. Clay, A Hebrew Deluge Story in Cuneiform (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1922), 39-41.

-

Shlomo Izre’el, Adapa and the South Wind: Language has the Power of Life and Death , (Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 2001), 5.

-

Canon John Arnott MacCulloch, ed., The Mythology of All Races (New York: Cooper Square Publishers, Inc., 1964), 175.

-

Antoine Cavigneaux and Farouk Al-Rawi, “Gilgameš et Taureau de Ciel (šul-mè-kam) (Textes de Tell Haddad IV),” Revue d’Assyriologie et d’Archéologie orientale 2, 87 I-III. Paris (1993), 92-93.

Yes, the price is that of thinking things through and leaving behind intolerance and willful ignorance.

I don’t buy it. Stubbornly believing things regardless of the evidence will NEVER EVER be the same as reliability. Reliability has to do with what works and getting the same results every time you use something. Reliability is something things MUST prove for themselves regardless of what you may want or believe. Reliability is the realm of science NOT religion and it is all about manipulation and control which only does harm in religion anyway.

I appreciate your point of view and I agree - somewhat. That is why I am going to put fourth some evidence that could soften your stance. Please be patient