There is strong evidence that Genesis 1-11 was written during the Babylonian exile. This is important, since understanding the date of its composition helps us identify the socio-historical context in which it was written, and aids our interpretation of the text.

Certain vocabulary in Genesis 1-3 is used elsewhere only in books written during the monarchy or later, such as ʾēd (source of water, Genesis 2:6), neḥmād (pleasant, Genesis 2:9; 3:6), tāpar (sew, Genesis 3:7), ʾēbāh (enmity, Genesis 3:15), šûp (bruise/wound, Genesis 3:15) ʿeṣeb (labor, Genesis 3:16), tĕšûqāh (longing, Genesis 3:16). The word Shinar (Genesis 10:10; 11:2), was used by nations outside Mesopotamia “to designate the Kassite kingdom of Babylon (ca. 1595-1160 B.C.E)”;(1) consequently its use here indicates Genesis 11 was written no earlier than the date of that kingdom.

(1) “Shinar The land of Babylonia, embracing Sumer and Akkad and bounded on the north by Assyria, modern southern Iraq.7 This name was not used in Mesopotamia itself but is frequently found in one form or another in Egyptian, Hittite, Mitannian, and Amarna texts to designate the Kassite kingdom of Babylon (ca. 1595–1160 B.C.E.).”, Nahum M. Sarna, Genesis (The JPS Torah Commentary; Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1989), 74.

The Hebrew phrase for “breath of life” used in Genesis 2:7; 6:17; 7:15, 22, is not found anywhere else in Scripture. However, it is found in the Eridu Genesis, a Sumerian text which was copied and read by the Babylonians.

Certain names appear only in Genesis 1-11 and books written during or after the Babylonian exile; typically they appear later in 1 Chronicles 5 or later books as personal names, and in Isaiah and Ezekiel as place names. Some names appear as personal names before the exile, but as place names only during or after the exile. A few names appear only in Genesis 10.

- Gomer (Genesis 10:2-3, 1 Chronicles 1:5-6, Ezekiel 38:6, Hosea 1:3).

- Magog (Genesis 10:2, 1 Chronicles 1:5, Ezekiel 38:2; 39:6).

- Madai (Genesis 10:2, 1 Chronicles 1:5).

- Javan (Genesis 10:2, 4, 1 Chronicles 1:5, 7, Isaiah 66:19, Ezekiel 27:13).

- Tubal (Genesis 4;22; 10:2, 1 Chronicles 1:5, Isaiah 66:19, Ezekiel 27:13; 32:26; 38:2-3; 39:1).

- Meshech (Genesis 10:2, 1 Chronicles 1:5, Psalm 120:5, Ezekiel 27:13; 32:26; 38:2-3; 39:1).

- Tiras (Genesis 10:2, 1 Chronicles 1:5).

- Togarmah (Genesis 10:3, 1 Chronicles 1:6, Ezekiel 27:14; 38:6).

- Dodanim (Genesis 10:4).

- Dedan (Genesis 10:7; 25:3, 1 Chronicles 1:9, 32, Jeremiah 25:23; 49:8, Ezekiel 25:13; 27:20; 38:13).

- Akkad (Genesis 10:10).

- Erech (Genesis 10:10).

- Calah (Genesis 10:11-12).

- Resen Genesis 10:12).

Some verses in Genesis 1-11 use place names which help date the text. In particular, several verses in Genesis 10 indicate the chapter could not have been written until after the reign of Solomon.

-

Genesis 2:14; 10:11. These verses refers to Assyria, which did not exist until the reign of Assuruballit I (1363-1328 BCE). The city of Assur was built earlier (around 2,500 BCE), but was ruled over by Akkadians, Amorites, and Babylonians in succession. Assyria did not become an independent state with Assur as its capital reign of Assuruballit I.

-

Genesis 10:11. This verse refers to Nineveh as part of Assyria, but it was not until the reign of Assuruballit I (1363-1328 BCE), that Nineveh became part of Assyrian territory. Note that Nineveh is mentioned in Genesis 10:11-12, but not mentioned again until 2 Kings, written during the exile; this supports the conclusion that Genesis 11 was not written before the exile.

-

Genesis 10:11-12. This refers to the city of Calah as “that great city”. Calah did not exist until 1750 BCE, and was a mere village until the ninth century BCE, when it became “that great city” during the reign of Assurnasirpal II, who made it the capital of Assyria. It could not have been called “that great city” until after the reign of Solomon.

-

Genesis 10:19. The boundaries of Canaan described here did not exist until 1280 BCE by a peace treaty between Ramses II and Hattusilis III in 1280 BCE; it is therefore unsurprising that the borders of Canaan described here do not match the description of Canaan in Genesis 15:18 or Numbers 34:2-12, or any text of Moses’ time. This verse could not have been written earlier than 1280 BCE.

-

Genesis 10:19. This verse refers to Gaza, but this location was first called “Gaza” during the reign of Thutmose III (1481-1425 BCE); it was not called “Gaza” before this time. It would have been known as “Gaza” by the time of Moses, but not in the time of Abraham.

-

Genesis 11:28, 31. These verses refers to “Ur of the Chaldeans”. The Chaldeans did not occupy Ur until around the tenth century (1000 BCE). The only pre-exilic use of the phrase “Ur of the Chaldeans” in the Old Testament is in Genesis 15:7, which was clearly written at least as early as the eleventh century (possibly by Samuel), by which time the term “Ur of the Chaldeans” was already the common term for the area. The only other use of “Ur of the Chaldeans” is in Nehemiah 9:7, a post-exilic book.

The text of Genesis 1-11 has a number of strong parallels with various Mesopotamian texts which were written very early, long before the birth of Moses.

The density of such references in Genesis 1-11 indicates these chapters were written for an audience familiar with these Mesopotamian texts. Hebrews living in Egypt (including Moses himself), would not have been familiar with these texts, which would have had little to no relevance to them. However, the Israelites taken captive by Babylon would have been exposed to the stories in these texts, to a greater or lesser extent; in fact the Israelites referred to in Daniel 1:3-4 who were taught “the language and literature of the Babylonians”, would have been taught to read and write these texts as part of their scribal training and cultural indoctrination. This is further evidence that Genesis 1-11 were written during the Babylonian exile at earliest.

The Mesopotamian textual parallels with Genesis 1-11 are not merely general, nor are they sporadic. They are typically very specific, involving not only identical concepts but even the same phrasing or words, as well as events in the same order. The level of detail in these parallels indicates strongly that they were not simply the result of a Hebrew writer demonstrating oral knowledge of stories he had heard; they indicate the writer of Genesis 1-11 had actually read these Mesopotamian texts, and was not only consciously aware of them but was writing in direct response to them.

However, Genesis 1-11 not only contains strong literary parallels with Mesopotamian texts, it also contains very strong anti-Mesopotamian polemic. That is, the text of Genesis 1-11 deliberately targets Mesopotamian religious beliefs and subjects them to contradiction, criticism, and even ridicule. This feature of the text is typically unnoticed by modern readers, since we do not share the same background knowledge as the original Hebrew audience, but for anyone familiar with the socio-historical background of the Genesis text, the meaning would have been very clear.

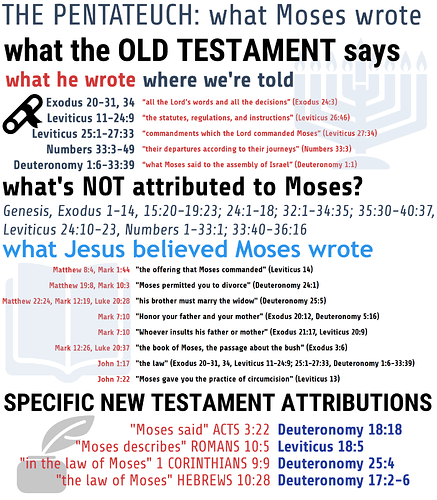

This infographic shows that none of Genesis is actually attributed to Moses, by the Bible itself.