You absolutely can legislate moral behavior. That’s what speed limits do, for instance, as just one example among a host of other things. (I do agree that the church has lost its moral authority, though.)

Indeed, and I’d be interested in @Jay313’s expanded thoughts on that as well.

unless i am very much mistaken, it seems there are laws prohibiting murder, rape, theft, assault, extortion, and a host of other immoral behavior…

I can’t tell if you’re being intentionally obtuse or you genuinely don’t understand the difference between facts, opinions, and values.

You actually think aesthetics is explainable by a set of facts? Good luck with that.

I didn’t say you can’t legislate moral behavior. That’s what the criminal code is.

Did you read the article that I linked?

I did indeed. Too bad William Wilberforce had never had a chance to read it. Maybe he might have realized the deeply problematic and ultimately self-defeating nature of his religiously-motivated crusade to legislate a particular morality on the rest of society!

Whew! Are we having a rough day?

I can’t tell if you’re being intentionally obtuse or you genuinely thought my comments were totally irrelevant and inapplicable to what I thought was a conversation. Let me repeat:

I should have have articulated more precisely. I certainly did not mean that all of aesthetics could be explained by a set of facts. I was just noting a couple of counterexamples to show that some things involving the aesthetic do indeed have facts attached to them, contrary to an unwarranted generalization that all aesthetic opinions and values have no factual basis. (And luck is not in my active vocabulary.)

No, you didn’t, but you certainly left that inference open as a possibility.

P.S.: It would be helpful if you parsed your sometimes lengthy replies per individual addressee instead of lumping them into one.

Haha. Well said. I’m tempted to reply that the exception proves the rule, but even Wilberforce wasn’t an exception to my point. I’m not sure how far we can get into this, since the forum has rules against political talk and abortion is the third rail, but I’ll try to speak in generalities. It’s getting late for me, but I’ll try to get back here in the morning and reply.

Yes. Sorry.

I try to limit my time on the internet these days. I only reply to things that draw my interest, and too often they’re complex subjects without easy answers. I don’t see a lot of difference between a long post addressing multiple people and multiple posts addressing individuals. If I carry on too long or you’re not interested, skip over it. I skip over a lot of folks.

There are counterexamples and there is disagreement for the sake of disagreement. Sorry if I mistook you for the latter. But I also get tired of repeating myself. It’s certainly possible to say that aesthetic opinions can have facts attached to them. I said more than once that it’s possible to make factual statements about aesthetic opinions. But what fact makes Beethoven more notable than his contemporaries? What fact makes a person judge the 9th and 5th his best symphonies, compared to the others? What makes one person value Da Vinci and another Monet? Who was the better artist? Can facts decide, or is it a cultural consensus?

Most of the “factual” basis of aesthetic opinion is passed down to us as a “form of life,” as Wittgenstein put it. (You should go back and read the excerpt from the article about him, if you didn’t the first time around.) The same could be stated about all forms of cultural knowledge, as well as our opinions of who is or isn’t “beautiful.” Many people from certain subcultures in the US would have no idea who or what I was talking about in the previous paragraph, for instance.

I’ve exceeded my time limit! More tomorrow …

Hi @Daniel_Fisher. Today got away from me a bit, but I wanted to reply briefly. Here’s the article in case anyone else is interested: Self-inflicted wounds: The Church and dissipation of Christianity in Europe

The main point that I took away from the article was the toxic combination of political power and scandal that marginalized the Catholic church in Europe. The same already had happened to the Protestant church, especially in those countries with an official “state church.” (The “Christendom” that Kierkegaard criticized.)

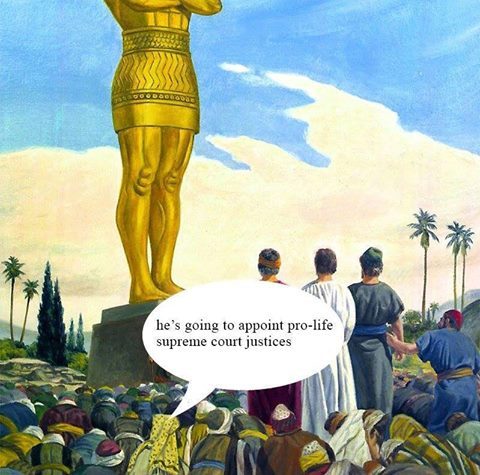

I see the same dynamic in the US. Wilberforce won the day by force of moral argument. He persuaded enough people to join his crusade to outlaw the slave trade with legislation. Win a consensus and pass legislation. That’s how “morality” becomes law in democratic societies. But that’s not what I see happening here. A minority of people support the moral positions that evangelicals want enacted into law. But instead of moral persuasion and legislation, as per Wilberforce, evangelicals tied themselves to one political party and tried to make an “end run” around the legislative process by appointing sympathetic judges. This was guaranteed not to win friends and influence people. Combine that long history of political power-grabbing with the abuse and financial scandals that recently have racked the church, and you have exactly the situation that dragged down Christianity in Europe. In just the last decade, the number of self-identified Christians in this country has dropped from 90% to less than 75%. I wouldn’t be surprised to see that number approach 50% or less in another decade, if the country lasts that long.

Not sure how much more I can say without running afoul of the mods, and since I’m running short of time, I’ll just leave it at that for now. Sorry for rambling. Too many distractions right now.

I largely agree… and the sentiment is not too far off from Lewis’s observation…

I do not, therefore, think that our hope of re-baptising England lies in trying to ‘get at’ the schools. Education is not in that sense a key position. To convert one’s adult neighbour and one’s adolescent neighbour (just free from school) is the practical thing. The cadet, the undergraduate, the young worker in the C.W.U. are obvious targets: but any one and every one is a target. If you make the adults of today Christian, the children of tomorrow will receive a Christian education. What a society has, that, be sure, and nothing else, it will hand on to its young.

But that said, I tend to look at these things as a “both-and,” rather than something we need to choose between. Ought Wilberforce to have devoted his attention exclusively on changing the heats and minds of the next generation, or ought he rather to have pushed efforts to push abolitionism through Parliament?

I would say, the answer is “yes.” And thus I think it to some extent a false dilemma.

Not to mention, I have seen even in my own life how, time and again, many of those within the masses assume, or come to believe, that something is in fact “moral” because it is decided as legal. Once something is established by the Supreme Court, that seems to end much debate about its morality, at least to some extent across the general population.

So I tend to think that this is like fighting a two-front war. Neither, alone, will achieve victory, and sometimes resources from the one must be diverted to the other, and I would agree that the “larger”, or “deeper” fight of the hearts and minds of the population at large is the true “center of gravity…”. But that said, insofar as changing the laws (either through legislative or judicial, or occasionally executive action) does in fact effect a change in the hearts and minds of a nation to at least some extent, I can appreciate the importance of both battles being fought simultaneously over two fronts.

Or, put more briefly, I could say I could agree with the article you linked to the extent that trying to change laws without also trying trying to change hearts will be a problematic and futile endeavor.

But to the extent that the article implies that we ought not try to establishing laws even while, or even after, we change hearts and minds, I to that extent demur.

One last observation… Now, I quite agree with many of the dangers inherent in Christians aligning to one political party, but I was a bit surprised by your thought…

I have a hard time perceiving this, I’d be very curious where you see this. Please feel free to send me a direct message if this will make the thread too political, but to my off-the-cuff memory, every major societal change significant to Christians in my recent memory came about by the opposing side going through the courts in order to overturn the democratic results that had been established through the legislative process.

If anything, it seems to me that the larger political sentiment or philosophy to which most Christians in the U.S. have aligned themselves is the one seeking to appoint judges who will return the legislative process to the legislature, no?

Very interesting post. A secular prof in my undergrad emphasized that point very strongly, that using the Court to legislate was unethical. He gave the example that even if Christians or another faith succeeded in legislating their creed as the compulsory State one, he would not try to stack the Court to overturn it…he would only try to reverse that the correct way…legislatively.

Having grown up as part of a very tiny, Christian minority, his argument struck me as unusually powerful.

Indeed. It strikes me just how much our mentality has changed over the years… if by chance we were facing an issue such as slavery, citizenship, poll tax, or women’s suffrage in today’s world, I think most people in our country would think it beyond obvious that the “solution” would be to take it to the Supreme Court and have the new policy established (or enforced?) through the courts.

But that was clearly not the mentality of our preceding generations. They seemed to think that, if they wanted to change policies of such weight and cultural impact, that they actually needed to amend the constitution itself and actually rewrite the laws themselves, not pack enough judges to be able to rewrite the laws from the bench.

I understand the urgency some feel in certain cases, and the text’s author noted (but disapproved of) FDR’s stacking the Supreme Court to get his Great Depression relief policies through. He wrote that the ends do not justify the means.

This may be too political, so @moderators, take it down if necessary, but it speaks to the end run around democracy, and is as applicable now as it was four years ago.

I don’t understand how talking about children being murdered and whether rulers who run kingdoms are wicked or righteous are problem topics.

It’s spoken of in scripture a lot.

Well, this ain’t the scripture. Seriously, the decision to limit politics and the discussion of abortion was made as those topics are emotionally charged and difficult to control and moderate as well as off topic in most cases to the faith-science discussion. Certainly things like the Covid pandemic has brought politics into play, but we try hard to avoid partisan discussions. Admittedly, some comments slip through, but any full fledged political debate or abortion debate will be deleted and participants socially distanced.

How about not using the term abortion and just talk about the wicked practice of murder, surely that would be inline with faith, love and obedience to God wouldn’t it.

Alas, this is not a general discussion board. I am sure you can find one elsewhere to post those sort of discussions.

Let’s move on.

Let’s see if I can return the discussion to generalities. Both of these options require swaying the hearts and minds of the present generation, whether popular opinion or a majority of legislators. That might take more than one generation, but the next generation is always the one that matters most.

What comes to mind as a relatively recent application is LBJ’s role in support of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. This was before the liberals and conservatives separated themselves into Democrats and Republicans. At the time, both parties contained liberals and conservatives. Johnson was a Southern Democrat, yet he persuaded his fellow Southern Democrats that both measures were the right thing to do. LBJ was not in the same moral universe as Wilberforce, but both won the day by winning the moral argument and persuading a majority to agree.

Our present tribal dichotomy has made moral arguments entirely irrelevant in persuading the public or legislators, but that’s how our constitutional system is made to work. If the Supreme Court interprets federal or state laws to be unconstitutional, the answer is not to stack the Supreme Court. Everyone recognizes that FDR’s talk about doing so is fundamentally unfair. (A moral argument.) The remedy is to pass legislation, and if the legislation won’t pass court muster, then a constitutional amendment is the remedy.

In short, if Christian morality has become unpopular, we should either convince the majority to change their minds by force of moral argument, or we should resign ourselves to living in the midst of “Rome” with wisdom and discernment.

I would argue that Christianity flourishes in its purist form when not aligned with the power of the state. But that’s a whole nother discussion …

How do we measure that Jay? Anyone?

It’s generally measured while you’re dying on a cross. When society is busy crucifying you for following Christ’s way, you can safely conclude that “Christian morality” must be a tad unpopular at the moment.