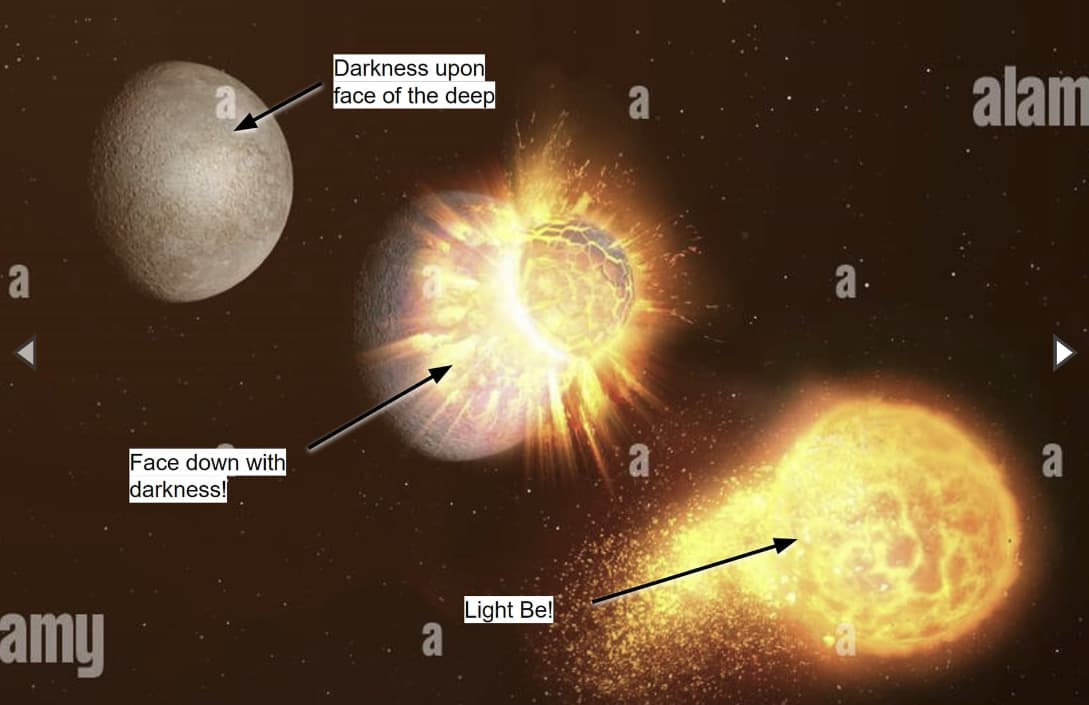

I still like what some ancient scholars, one of whom lived before Charlemagne, found in the opening of Genesis: that the universe started out smaller than a grain of mustard (i.e. the smallest possible), that it was filled with fluid (waters), that it expanded rapidly beyond comprehension, that as it expanded the fluid thinned at at some point got thin enough that light could move, at which point God commanded light to be; that the universe is ancient beyond measure, and that the Earth itself is ancient beyond counting.

Though some gave numbers for these, they tended to be symbolic; one given for the universe was a million times a million, one for the Earth was ten thousand times ten thousand. The first is 1000^4 or 10^{12}, i.e. a trillion; the second works out to a hundred million. Both of these figures diverge from what science yields, but they weren’t doing science, they were doing theology via numbers – 1,000 is 10 x 10 x 10; ten stood for a task done, and raising it to the third power indicated something superbly well done, then raising that to the fourth power indicated it as divinely well done. “Ten thousand times ten thousand” works out similarly.

Numbers aside, those ancient scholars, purely based on the Hebrew described what much later got dubbed 'the Big Bang" just by studying Genesis – their description corresponds to Genesis 1:1-3.

The “great deep” of “the face of the deep” is תְה֑וֹם (teh-home), “t’hom”, which is endless water and endless darkness. With endless water, there was no room anywhere for land.

As ‘royal chronicle’, the Creation account is about a great king’s mighty accomplishment. In this case, the first move is commanding light into existence, denying the supremacy of darkness, which is seen as having substance, not just as the absence of light. The second is giving the two opposing entities names – “day” and “night”. Having the name of something in that ancient worldview meant having power over it, so besides having broken the dominance of darkness YHWH-Elohim now commands both darkness and light, which leaves the waters and their chaos.

His next move is to open a space in the midst of the t’hom; by creating a raqia, a “firmament”, and pushing the waters apart, YHWH-Elohim beats the t’hom and establishes His own realm which He names “heaven”.

Next into the space He has made, which could be called a “water world” even though it isn’t really a world yet, God gathers up the waters at the bottom of the raqia dome and pushes them aside to raise up dry land – and again He names the two things, the water and the land, establishing His authority over them.

In one way it’s a typical ancient near eastern creation story, starting with the t’hom and going on to have dry land, but there’s a big difference: in the typical ANE story, the gods have to fight to defeat the great deep, exerting themselves; here, we see a battle but not a fight, or at least not the same kind of fight – YHWH-Elohim does battle by sheer creation and command and naming, not so much winning as just declaring His supremacy.