This is another distortion of what I said

- A.

- The words you ought to be using are: Abstract points and Concrete points. Both are actual, one is not physical and the other is. There are an infinite number of Real Numbers, which are Inanimate Abstract things. And there are an infinite number of instants in Absolute Time and an infinite number of points in Absolute Space.

- B.

- Russell’s 1st premise is that "the number of things in the world may be finite, but seems unlikely.

- His implied 2nd premise is that “an infinite number of things in the world is likely”.

- The latter being the case, there is an infinite collection of trios in the world.

- C. All of which is off-topic.

![]() Guilty as charged. This is what caught my attention, and I wanted to comment nearly was all that is needed.

Guilty as charged. This is what caught my attention, and I wanted to comment nearly was all that is needed.

You didn’t learn about nuclear warheads.

That’s the radical reformation’s take, but it is not the understanding of the Wittenburg Reformers. To the radicals, sola scriptura was the answer to “What is the one place to learn about God?” but to the Wittenburg Reformers it was the answer to “What is the highest theological authority?” It was meant in the same sense that Cyril of Jerusalem and Gregory of Nyssa taught when they called scripture “our proof”, “the rule and norm”, and the “umpire” of the faith.

Ironically the heirs of the radicals have never been consistent since they teach the Trinity and the two natures in Chris quite in accord with the great Councils, which unfortunately many of the heirs of the Wittenburg Reformers have drifted towards the radical view.

What has always struck me as odd is that the radical definition isn’t biblical!

Malangelism? or to not mix language roots, dysangelism?

Except the syllogism is incomplete because it does not state a meaning for “truth”, and in fact relies on an unbiblical one, the scientific materialist version that only that which is scientifically accurate is true (an odd definition given the nature of science!).

They should all be required to read Origen on the topic, at an early age – Origen defines something like seven levels of meaning of “the Word of God”, of which three are found in the Bible, where each level supersedes those that follow – the first of course being the Word made flesh.

And nuclear war.

Well, so long as there is not an infinite number of verses in the Bible…

Way back, many years ago, I was born into a family in a branch of the Lutherans that believes in verbal inspiration. We definitely were taught that the bible is God’s Word, word-for-word inspired, and God is incapable of lying so the bible must be word-for-word true. This always did mean the words originally written, in the original language, so the validity of sources, and the accuracy of translation were things that had to be carefully evaluated. In parochial elementary school, high school, and especially the two years of pre-ministerial college I experienced, this was not to be questioned.

In recent discussions with my brother, he gave me an explanation echoed from one of his seminary professors: If we don’t believe that everything is absolutely true, then we will not be able to tell what is true and what is not. This gives me the impression that an important characteristic of those who are attracted to the strictest interpretation of inerrancy have a serious difficulty in dealing with uncertainty, and want to believe that they have a source that can be absolutely relied on. This also leads my brother (and his former seminary professor, in an article my brother sent me) to reject even the possibility that his belief in verbal inspiration could be wrong, and to consider anyone who believes differently to be a heretic, trying to undermine the true Word of God, even those who profess their belief in Christianity. And, no, the teachers and preachers are not making (and will not make) any efforts to honestly expose their students to other ideas or interpretations.

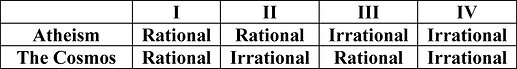

putting the shoe on the other foot, anyone claiming atheism is irrational would first have to show it was untrue.

Not to derail the conversation too much, but some thinkers (theistic epistemologists) and Plantinga himself have argued that atheism is irrational. I don’t think I would make a claim this strong personally, but I do see at least some merit in the self defeating nature of naturalism (not necessarily atheism, but pure materialistic naturalism + atheism).

Plantinga’s EAAN is subtle:

- If naturalism is true, our minds, consciousness, language, beliefs, etc were selected for their survivability, not necessarily for truth tracking (they track truth insofar as tracking truth is beneficial for survival, and ignore it when survivability trumps truth)

Note: The naturalist will be familiar with this argument if he/she accepts evolutionary debunking arguments for religious, supernatural, and/or moral beliefs - Under naturalism, a “thought” is a biochemical reaction that is determined by external factors; agency and consciousness are illusory because the mind has no ability to affect external reality. -This argument needs to be made probabilistically because the naturalist can argue consciousness is an emergent property of natural selection (even if they accept mind has no ability to influence reality)

- The naturalists’ belief in naturalism itself was thus created by an unreliable belief-forming mechanism, i.e. the human mind, which is only a product of external and natural forces. Therefore, the naturalist has a defeater for their belief in naturalism itself, and any belief they claim to be “true”. This point was echoed by Charles Darwin:

But then with me the horrid doubt always arises whether the convictions of man’s mind, which has been developed from the mind of the lower animals, are of any value or at all trustworthy. Would any one trust in the convictions of a monkey’s mind, if there are any convictions in such a mind?

Of course, if one is an atheist but not a naturalist this argument goes away.

In recent discussions with my brother, he gave me an explanation echoed from one of his seminary professors: If we don’t believe that everything is absolutely true, then we will not be able to tell what is true and what is not.

This is an argument I hear in my church all the time. I like them, but we can’t argue from a basis of wanting something to be true.

On the other hand, all of us who adhere to a system of faith do, to some extent, apply that leap.

What do we mean by inerrant?

I don’t see any coherent meaning of this term applicable to the Bible where it isn’t much more communicative simply to use a different word for it.

Word of God? Sure. You can trust telling people to read it for themselves for some communication from God? Yes. But inerrant? I don’t see it. Infallible? I don’t see that being a good word for it either.

Inerrancy usually refers to original manuscripts (which we do not have).

Yeah… if the meaning of “inerrant” depends the particular text then, I don’t see how it is coherent.

Are churches still guided by God/the Holy Spirit (and how can we know)?

There is a difference between “guided” and “controlled.” I think the inspiration of God pours down upon us in a torrent. But this doesn’t mean that everything is perfectly from God – far from it. Likewise guided by God/Holy Spirit doesn’t mean that churches cannot lose their way.

Word of God? Sure. You can trust telling people to read it for themselves for some communication from God? Yes. But inerrant? I don’t see it. Infallible? I don’t see that being a good word for it either.

I’ve settled on saying it could be without error. In my experience, more often than not, alleged errors from skeptics I’ve come across have very simple explanations based on the context of the passage. Other times a good evangelical commentary helps me understand something I wasn’t aware of before. And then there are those really hard ones that don’t have a good explanation. I don’t have so many of those. I don’t go looking for them. But I do look up what doesn’t make sense as I go along.

Genesis 7 was a big one for me that had a great explanation. Paul’s statement that the woman was deceived was another one that opened up a whole new revelation for me. There’s also a verse in Hebrews about unintentional sins that is purely outstanding too.

The sola scriptura principle as held by the Wittenburg Reformers can be found in the church Fathers, who called scripture things such as “the referee” and “the measure”.

Yet the view the early church called inerrancy wasn’t about there being no errors in the text, it was about the message striking where God “aimed” it. They were much less concerned about scripture being “reliable” than they were about it being effective.

I agree. It has been interesting to read about the attitudes of early Christians to the scripture (prophets and the apostolic teaching). I assume that understanding it would change the perspective of at least some believers.

It was illuminating to understand how the early Christians believed in the teachings of Christ as told by his apostles. At the start, there were no NT writings, teaching was spread orally. Soon there were also written texts. The attitude was that the orally mediated teaching and the written text were equally important because they contained the same teaching. No need to invent ‘sola scriptura’ because it did not matter whether you read it or heard it, it was the same teaching.

Later the importance of the written apostolic teaching was stressed, perhaps to shoot down heresies that were not based on the apostolic teaching.

At one early phase, there was also a tendency to stress the importance of the orally ‘tradition’, the chain of teaching from the apostles to their pupils or successors, as a quarantee of correct apostolic teaching. This was needed because some heresies, for example some versions of ‘Christianized’ gnosticism, interpreted the scriptures in a weird way to support their teachings. Irenaeus and Tertullian lived during this phase and their writings demonstrate this attitude and need. At this point, the time of apostles and their pupils was recent history and the apostolic teachings were therefore still in the ‘fresh’ memory of the successors, in the sense that it had been told by the pupils of the apostles or ‘pupils of pupils’. ‘Tradition’ and scriptures were therefore still the same teaching, assuming that you did not twist the interpretation of the scriptures badly.

A need for ‘sola scriptura’ emerged much later when the content of the ‘tradition’ changed from the original apostolic teachings to the teachings of much later church fathers, councils and popes.

If we would still understand ‘tradition’ in the same sense as the early Christians, I guess even protestants would be happily talking about the need to have ‘the apostolic tradition’ in both forms, the written texts and the teaching of the church.

Edit:

Maybe it is healthy to remember that the early teachings were not a strictly defined rule. It was extremely important that the essential core teachings were told correctly but otherwise, there were probably more variation in the teachings of early Christian writers (apostolic and church fathers and other respected writers of that time period) than you can find opinions among the members of a church today.

One reason for the apparent variation in teachings may be that the first Christians did not have a uniform theological vocabulary in use. Although they tried to express the same truths, they used so different language and words meaning something else to us that a modern reader may become confused.

It was illuminating to understand how the early Christians believed in the teachings of Christ as told by his apostles. At the start, there were no NT writings, teaching was spread orally. Soon there were also written texts. The attitude was that the orally mediated teaching and the written text were equally important because they contained the same teaching. No need to invent ‘sola scriptura’ because it did not matter whether you read it or heard it, it was the same teaching.

Later the importance of the written apostolic teaching was stressed, perhaps to shoot down heresies that were not based on the apostolic teaching.

I mostly agree in general but I don’t think the part I put in bold is entirely true in all cases, places or times in the early church. Papias writes:

“For I did not think that what was to be gotten from the books would profit me as much as what came from the living and abiding voice ” (Ecclesiastical History , 3.39.4).”

Oral tradition may have been preferred even after the four gospels were all written though some of them probably did not have much time to disseminate yet. And of course Papias does favor and defend the Gospel of Mark and mentioned something about Matthew (which may or may not be our complete Gospel of Matthew since most do not believe it to be a direct translation from Aramaic).

The important part is that Papias is interested in reliable voices and writings and yes, both are used side by side. He did, after all, compose his own 5 volume work of expositions on the saying of the Lord. Of all the writings lost to history, Ineould love a copy of Papias writings to be found. It would illuminate a lot of NT research. But based on his own writings, it almost looks like that at the time, oral voices from those who heard the apostles directly were preferred by Papias.

Vinnie

At the start, there were no NT writings, teaching was spread orally. Soon there were also written texts. The attitude was that the orally mediated teaching and the written text were equally important because they contained the same teaching. No need to invent ‘sola scriptura’ because it did not matter whether you read it or heard it, it was the same teaching.

One caveat: in the late second temple period the “two powers in heaven” concept was common, as was the acknowledgement that God’s Spirit was distinct from God the Father (though they wouldn’t have put it quite that way), and despite common belief the idea that the Messiah would have to suffer and even die was common – including recognizing Isaiah 53 as referencing the Messiah, not Israel the nation (of course there were other views as well; an interesting one was an expectation of three Messiah figures, a prophet, a high priest, and a king).

So among the Jews there were many who were “prepped” with the Suffering Servant expectation, plus there were other themes that pointed to the Messiah that fit Jesus well. These were all derived from the scriptures, if not always directly or what we would consider logically, and thus the Old Testament was “the scriptures” right from the beginning.

For these reasons I suspect that the majority of the early elders (priests) and overseers (bishops; head elders) appointed by the Apostles and even into the second generation were Jews who understood the Old Testament to be saying everything that the Apostles ascribed to Jesus. And it hardly needs saying that they would have been men with prodigious memory, able to recite both Old Testament and the teachings of Jesus without mistakes.

One reason for the apparent variation in teachings may be that the first Christians did not have a uniform theological vocabulary in use. Although they tried to express the same truths, they used so different language and words meaning something else to us that a modern reader may become confused.

The vocabulary issue continued for nearly four centuries. It also contributed to a split in the church that was not actually about doctrine – since both sides taught the same things – but was a difference of vocabulary due to a different heresy being the primary one those on the different sides faced.

There was variation in how people responded to the written text, that is true. As long as there were apostles or their pupils available, that may have been the most trusted source.

It is not obvious to me which writings Papias ment when he wrote his text. There were all kind of writings circulating around. There is also the weakness that books were not interactive. The teaching was preserved but there was no possibility to ask clarification or something that was not included in the books.

Yes, as long as the elders were Jews the roots to the Hebrew scriptures and tradition remained strong.

As far as I understood, there were different interpretations available among Jews. Some interpretations appeared to come close to what Christianity later told.

Palestinian Targumin told that when human was created, those creating were God, word of God and glory of God (sounds almost like trinity).

In Alexandria (especially Philo), there was much talk about Logos because that fit well to the attempts to find connections with Greek philosophy, the ‘science’ of that time. I do not remember what the teachings were exactly but I remember that some sentences sounded almost Christian, although that was not the intention of the Alexandrian philosophists.

I’ve never seen anyone claim there are an infinite number of stars. Have you? Do you have a reference? Has anyone in the history of science or mathematics claimed such a thing?

I can’t answer that but Olber’s paradox comes to mind. Wasn’t that meant to address an infinite universe?

Of course, the size and expansion of the universe kind of renders it obsolete.

I’ve found Reformed epistemology offers an alternative to evidentialism (the view that religious belief must be supported by evidence in order to be rational) and fideism (the view that religious belief is not rational, but that we have non-epistemic reasons for believing). One of Plantinga’s points in his 2015 book Knowledge and Christian Belief is a suggestion that we can know things to be true through the Holy Spirit, and this can include certain truths when reading the Bible.

I think I would be interested in the “certain truths” because there are a lot of Christian’s who prayerfully read scripture and come away with different doctrinal beliefs and even stances on certain moral issues. I can’t imagine the same Spirit is giving conflicting advice. And yes, I realize it’s easy to mistake your own views for what the Spirits is teaching but this just has happened to too many Christian’s over so many issue I really can’t buy it. I believe the Holy Spirit comes to us as we read scripture but our experiences also act as a filter restricting what we allow the Bible to teach us. I am more comfortable to think of God moving us in certain directions as opposed to just giving us facts or beliefs. I also think just as God accommodated his message through ancient cosmology and patriarchy, it may be that as we read scripture, his message is accommodated through our own mistaken and limited views. But if you don’t think God accommodated scripture and it’s all factually true and your special brand of aChristianity gets it right where all others don’t we might confuse the scripture speaking to us through our beliefs as the Holy Spirit validating our beliefs. I can personally see a distinction here.

One of the issues your point brings up is the epistemology of reason itself. Its a weird question but I’ll ask it anyways: why are we justified using reason as a method of coming to truth. Can we use reason to prove or argue that reason itself is (the/a) way of coming to truth? The answer seems to be “no,” and unfortunately this leads to an infinite regress. Foundationalism on reason (a good choice IMO) seems to have epistemic parity to belief in God, and is indeed strengthened/supported by belief in God (one of Plantinga’s points).

It’s a great question. How can I even trust my brain or that I even have one? Why trust logic? Am I just developed to believe x and y whether it corresponds to reality or not? I do enjoy occasionally dabbling in philosophical skepticism. I remember reading Hume’s thoughts on how cause and effect were not logical. Just because the sun rose 1,000,000 days in a row does not logically necessitate it will again. Or just because the laws of nature have been constant for x billion years does not logically necessitate they will be tomorrow. Fun to think about and maybe even more so after a few pints otherwise the brain starts smoking.

I’m sure we can know many things without logical syllogisms and scientific data but I am weary of the “Holy Spirit told me x” in the context of “this doctrine is correct.” I’d prefer to think the Holy Spirit is working with what’s in front of Him to move us in the direction God wants.

But the Bible doesn’t claim it is true