I would agree that indoctrination is a normal and healthy part of teaching. It’s nothing more than passing on the accumulated knowledge of those who came before us. You can’t add to that knowledge until you understand how we got to where we are now. In the sciences, you can’t overturn the consensus until you learn what the consensus is. High school science classes are almost entirely indoctrination, and that’s a good thing.

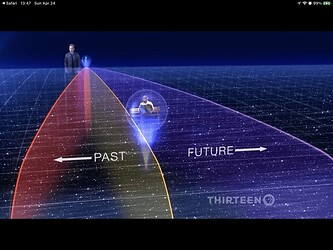

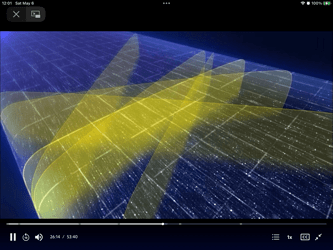

Of course Christians believe we have revelation, doctrine, from and about our ‘preexistent’ God, to frame it in temporal language as we must. I just ‘now’ seconds ago sent an email to my sons about the NOVA we were talking about over coffee before they had to leave, on the illusion of time and the varying ‘now’ spacetime slices.

And I see nothing wrong with teaching those beliefs. It’s rather silly to expect each new seeker to figure out all of Christian theology on their own. The only caveat I would have is that we not use government resources to teach religious beliefs, the whole “separation of church and state” thing.

I would fully agree that something like a “World Religions” course would really benefit high school students.

In the U.S., most people don’t realize the 1st Amendment was meant to protect state established religions from the newly formed federal government. Kind of ironic something so simple would be distorted with the passage of a 100 or so years.

From the very start the idea was that government resources should not be used for religious indoctrination.

The 14th Amendment applied the 1st Amendment to the states.

Due process clause, right? If a state today wished to use state funds for schools of religious education it’d be perfectly constitutional as long as it does so in an equitable manner.

Congress shall make no law… very specifically and meaningfully the prohibition was with respect to the federal government

That has led to some interesting outcomes.

And the 14th Amendment very specifically and meaningfully applied these restrictions to the states.

Yes and without restricting a state from funding religion in an equitable manner.

Are you seeing something I don’t see: “no person shall be deprived of life, liberty, or property without due process of law”

I’m seeing the rest of the amendment.

Like I said, no restriction on a state funding religion in an equitable manner.

Again, this distorts the meaning of the 1st Amendment. If anything it was a wall of separation between church and federalism. And the due process clause protects an individual from having their rights taken away as the result of a religion.

If a state wished to fund schools of religious education in such a way that no religion would be excluded as long as it complied with the same basic requirements that private schools have to comply with now, then there would be no contradiction with the 1st or 14th Amendments.

Somehow I lost track of this thread; here goes trying to catch up.

Oh, the irony! Bultmann wanted to make Christianity look rational, and to strengthen it by demythologizing the scriptures.

His denial that Christ had an eternal existence before the Incarnation was the step too far, though.

Too bad about fifty million more Christians aren’t so wise.

Wow – that’s a great way to put it!

I don’t get how people can come to that conclusion at all. God working through evolution is no different than His working through geology or even the weather.

I think that’s pretty obvious to any objective observer.

Interesting. I’d love to hear that expanded on.

An awful lot of modern heresy is driven by the urge to make God fathomable. I always found that baffling, since if God is fathomable to us He’s not much of a God at all. I generally figured that He is at least as far above Nobel Prize-winning physicists as those physicists are above a high school dropout (Neil DeGrasse Tyson does something illustrative of this with his point that if we are just a few percentage points above chimpanzees in intelligence, an intelligence that is just a few percentage points above us would be essentially unfathomable to us).

I find mystery in creation due to Paul’s description of Jesus as the “firstborn”, which is a Greek philosophical term used to mean “opener of the way”. Without going into details, that means that everything in existence was shaped by Who Christ is, which in turn means that every last and little thing in creation tells us something about our Savior! So the palm of a human hand, a fallen maple leaf bobbing in a stream, a lone snowflake falling where no others are visible, a burst of lava shooting up from a cinder cone, a bacterium with the new ability to metabolize arsenic, all express something about Christ Jesus – but I expect that if I could live ten thousand years I would never figure out more than a few far simpler instances, leaving that maple leaf or burst of lava in mystery.

It should be noted that various places in scripture use what has been called “teaching by contradiction”, where two different ideas are set out and the reader is supposed to grapple with the text and resolve them. That approach to teaching, a favorite among some first-century rabbis, is part of the context of scripture. Similar to it and more common in the scriptures is to make a statement that on the surface seems not all that consequential but which when pursued with additional knowledge from the earlier scriptures delivers a potent message. This was even more common in first century Judaism, and Jesus uses it in ways that to us seem opaque because we’re not accustomed to thinking that way but which to (for example) the Pharisees was clear – just not clear enough to bring any accusation (my favorite example of this is when Jesus, referring to Himself, said that “One greater than the Temple is here”: in Second Temple Judaism the only entity greater than a temple would be the deity whose temple it was, so by declaring Himself greater than the Temple Jesus was asserting His identity as Yahweh).

So part of the context that we have to understand is that they had methods of teaching that are alien to us, to the point that if we fail to grasp them we totally miss the importance of more than a few things.

They probably recognized that there were contradictions, but it didn’t bother them because they didn’t see how to present truth the same we we do. Thanks to a culture of scientific materialism, we want everything to be objectively and logically consistent, and that’s what we regard as authoritative, but back then authority depended on the source – so since God was considered to be the source behind the two stories both were regarded as authoritative despite the differences.

Yes, it’s found in Luke; it’s also found on its own, and if I’m remembering correctly from grad school it’s also found in at least one different place in John.

The vast majority of the variants just show that people aren’t perfect so there are differences in spelling, word order, and even missing clauses, all due to fallibility. The more interesting ones serve as theological commentary since they are obvious attempts to make something clearer or more palatable.

The more potent lesson from the variants is that God isn’t particularly interested in an inerrant text since He could have made the text passed down with no mistakes or ‘corrections’ yet didn’t do so. I find in this a reminder that our faith is not in the scriptures but in the living Word.

Superb lesson! I’m going to have to keep that in mind for the next time I feel like giving up.

Sometimes the effort to make things clear just makes them entirely different than they actually are. Atheists who insist on an explanation for God of the sort we might give for a new species of centipede are just being thick - as are the Christians when they insist certain points of theology are clear when all they mean is that their interpretation makes the essential points of their creed internally consistent. Pin it down too much and it becomes something banal.

just being thick - as are the Christians when they insist certain points of theology are clear when all they mean is that their interpretation makes the essential points of their creed internally consistent.

On this point I’m frequently thankful for professors who emphasized sticking to the text, whether it was Greek or Hebrew or cuneiform or whatever. It’s too easy to try to make things conform to previously held beliefs and usually we don’t even recognize when we’re doing it. In a course reading through Mark the professor surprised us by accurately guessing which translation we were each most accustomed to because it showed up in our translations of passages in Mark – the hard lesson there was to climb out of our existing worldview and venture into the one held by the writer (I recalled that later when reading Egyptian stuff, and found myself thinking, "This is just too different!).