While some debate surrounds the gait and locomotor efficiency of the species, it is fairly well accepted that they were habitual bipeds that retained some arboreal characteristics in the form of upward-oriented shoulder joints, an ape-like scapula, a high intermembral index, and curved finger bones. Their innominates and lower limbs were unquestionably those of a biped, and the big toe, while slightly divergent from the other four digits, was not nearly the grasping digit seen in apes. The buttressing of their ilium, in the form of the iliac pillar, shows that weight was being transferred through the bone in the same manner as our own. While there is evidence of the bicondylar or carrying angle of the femur, the femoral head was small and the neck (narrowing below the head) was longer in australopiths and paranthropines (i.e. robust australopiths—see Chapters 16–19), relative to Homo species. Lovejoy believes that the degree of lateral iliac flare and long femoral neck in australopiths were associated with increased leverage of the deep gluteal muscles so that they were more biomechanically efficient than modern humans (Lovejoy 1988). As we gave birth to larger-brained infants, our pelvic aperture had to expand laterally so that the femoral neck became shorter and the deep gluteal muscles became less biomechanically stable relative to australopiths. The bony elements of the Homo pelvis and hip had to become more robust to handle the increased force that the gluteal muscles generated on the bones (discussed in Lovejoy 1988 and Cartmill and Smith 2009). Based upon the Laetoli footprints, it appears that the feet of Au. afarensis were slightly inverted, which would have helped with climbing.

AU afarensis had a prognathic, ape-like face (see Figure 11.8), a primitive skull morphology, and a small brain averaging 420 cc. They exhibited a slight sagittal crest for attachment of the temporalis muscle and a more pronounced nuchal crest, where their nuchal (posterior neck) muscles inserted on the posterior skull. The two crests were compound—a compound sagittal-nuchal crest—meaning that the sagittal crest converged at the center of the nuchal crest. Their teeth were large and their dental arcade was U-shaped, and thus more ape-like. The lower first premolar suggests a transitional phase, termed semisectorial, between the honing, sectorial (single-cusped) premolar of the apes and our more bicuspid premolars. The canines were monomorphic. Like Au. anamensis, their molars were expanded.

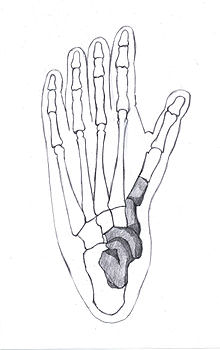

While their hands were capable of a precision grip, they did not have the same degree of mobility in their thumbs as later species of australopiths and paranthropines. The conical thorax is linked to climbing and a large gut, and possibly the degree of lateral flare of the iliac blades.

Both quotes from here. There are any number of other resources out there, some more reliable than others. I would have used Wikipedia but somebody inserted a sentence I disagree with, and editing the article so I could reference it here seemed a tad disingenuous.