Well, Merv was quite correct to say that nobody is arguing for “design from scratch”, and in the recent posts nobody seems interested in “bad design.”

That leaves your question here, of “how something was designed.” Or, if we use EC terminology, “how something was created [through evolution].” The first thing to remember is that this focus shifts the question from “Is there any sign that God was involved, given contingency, doubtful design principles etc?” to “How did God create this?” - which under most understandings of the word “creation” means that God knew what he was doing, ordering, allowing etc. For example, few people would believe that if I cut myself shaving, I have “created” a new pool of blood.

But part of my point was that even that question, “How did God create [the specific example of] the giraffe with its recurrent laryngeal nerve?” is pretty uninteresting if the answer is just “It evolved that way, somehow.” Why does the leopard have spots? “It evolved that way.” How come tigers have stripes? “they evolved that way.”

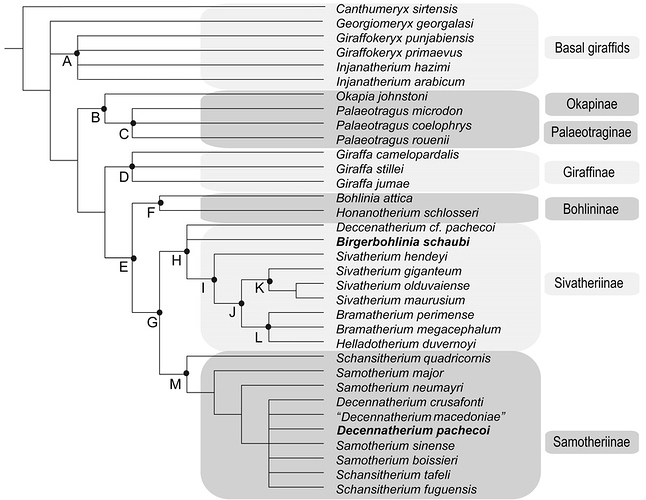

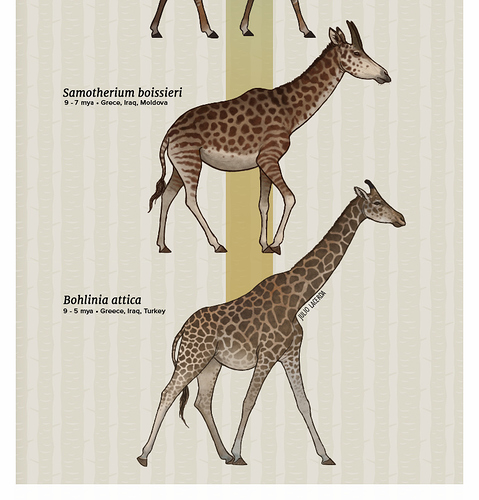

We have no idea why there are giraffes, given that Lamarck’s and Darwin’s shared idea that they needed to reach high leaves to compete has been debunked, and also the principal alternative, sexual selection.

We don’t know that it evolved gradually, because long-necked giraffes appear suddenly in the fossil record. “A gradual transition may have existed” is not evidence to me, but a hoile in the evidence requiring plugging. Andreas Wagner would probably be among those who wonder how the huge suite of special adaptations that is a giraffe could co-evolve gradually under no very obvious selective pressure. Perhaps it was neutral evolution, then - but still super-coordinated.

And in the midst of all that magic, the recurrent laryngeal nerve doesn’t take the opportunity to evolve. Knowing why might help a lot in understanding evolutionary constraints, developmental constraints - or even design principles.

As I pointed out, a direct LRLN occurs as a rare variant in humans, and so probably in other species of the thousands or millions of animals that have shared the trait. We therefore know nature can do it (and have the result survive). If there was an evolutionary advantage, then now is the ideal time to see, because the human population is no longer small, but huge (my estimnate 1/4 million “direct nerved” individuals). Natural selection of traits is far easier in large populations (as pevaquark implies), so the fcat that the trait shows no sign of getting more common somewhere implies there is no selective advantage. So logically maybe there’s a selective advantage to the conservation of the recurrent nerve form.

The trouble is that when we have no idea of the advantages or disadvantages, simply to say X or Y could have happened because an appropriate fitness landscape existed tells us nothing about how God created through evolution - or even how evolution created through evolution. It’s as useful as a historian saying that wars will be won if the circumstances are suitable, and lost if the circumstances are suitable for that outcome.

Given the wonder that is a giraffe, and the marvels that enable it to be one, it’s astonishing to me that anyone would pick on one anatomical anomaly (which works perfectly well in the giraffe as in the human), and comment on God’s non-involvement. But people do - apparently to get at some Aunt Sally “Creationists” of one stripe or another, who are held to believe that God zaps human engineering wonders into instant existence.

But Wolf-Ekkehard Lönnig, mentioned above, for example, has been far more critically conscious of the evidence of giraffe evolution than someone like Richard Dawkins, whose “how” answer is that evolving a long neck is easy, and the recurrent laryngeal nerve bad design.

Just remember how Lamarck and Darwin’s “giraffes evolved to reach high food” was taught to all of us at school as a classic example of natural selection until, a relatively short time ago, somebody actually studied the giraffes instead of the theory, and found the story was false.

Final point in a rambling collection of points: what is true in considering the “evolutionary creation” of the recurrent laryngela nerve - that is, “How did God achieve this end?” also applies to the original subject of this thread. If the human reproductive system is “badly designed”, then evolutionary explanations for that achieve nothing if one believes that “God creates through evolution.” If some things have evolved “badly”, then God creates through a badly designed evolution, or God creates only certain things through evolution, the rest being beyond his control, or God does not create through evolution at all.

If someone wants to exclude certain things from the EC “process”, they’d better be able to define criteria for whih bits are God’s, and which not, and justify that “two creator” position somehow.