Excellent points: thank you

This piece just came out in FiveThirtyEight. It doesn’t seem to have a lot of new data but cites what is probably the best we have right now. The emphasis is on sexual morality (same-sex marriage etc.) but one main message is that theological hard-ass-ness is no longer the source of strength that it seemed to be a generation or two ago.

Just wondering: do you think that figures of speech should accurately describe reality? For example, when Isaiah 55:12 talks about the trees of the fields clapping their hands, does the fact that trees don’t have literal hands that they literally clap somehow undermine the authority of the Bible?

That piece is well worth reading, whether you agree or disagree with his progressive-leaning conclusions.

This shocked me, but sounds about right: “The median age of white evangelical Protestants today is 55.”

Wow.

Here’s the research that generated the article: America’s Changing Religious Identity

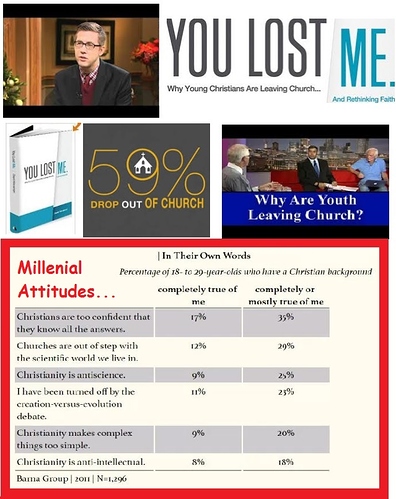

For some time, I’ve been collecting data on the phenomenon of the younger generation abandoning the church in record numbers, and this particular study goes against the grain of everything else that I’ve seen. The authors are recycling the standard line of evangelicals since the 1980s, which was that mainline churches were losing members because of their “liberal theology.” (The author reveals some serious bias when he equates the “liberal theology” of mainline Protestant denominations with that of the heretic John Shelby Spong, who denies the resurrection.) For the most part, there is a small grain of truth to that, but as an overall explanation, it is sorely lacking. As proof, evangelical churches have, in the past decade, joined their more liberal brethren in losing the younger generation.

Anyway, here’s why I think that study is problematic: 1) It was conducted in Canada. As we all know by now, the U.S. has a stand-alone problem with YEC teaching and evolution. 2) The research focuses on reasons that certain churches in the area were growing while others were declining, but that is looking in the wrong direction. People could be changing churches while the overall percentage of Christians in the area remained steady. In that case, it might be helpful to know the reasons that some churches were more successful than others. However, that isn’t the problem. The real problem in this country is that the overall number of Christians is dropping like a rock across the board, in both “liberal” and evangelical churches. The research that must be done is asking those who left about their reasons for leaving.

Unfortunately, such studies are few and far between. Here is one study of Presbyterian Baby Boomers from 1993, and the results are somewhat surprising. Participation in the so-called “counterculture” of the 1960s-70s – the flashpoint that set off the “Culture War” – had almost no effect on whether Baby Boomers left the church or not. As the authors put it:

Involvement in the counterculture is associated with unorthodox theological views, as well as with liberal positions on controversial issues of sexuality, reproduction, and gender, but it is not a good predictor of church involvement itself. … In our study, the single best predictor of church participation turned out to be belief – orthodox Christian belief, and especially the teaching that a person can be saved only through Jesus Christ.

In short, for the Baby Boom generation, the reason people lost faith was not the sexual revolution, drugs, feminism, gay rights, abortion, modernism, post-modernism, relativism, naturalism, liberal media bias, nor any of the other “evils” targeted by the Culture War. The answer was actually much more simple and straightforward: People left when they stopped believing that Jesus was “the way, the truth, and the life.”

The problem now is that 25 years of Culture War have passed since that study, and Millennials are departing for different reasons than their parents, reasons that have as much to do with the marriage of religion and politics that has taken place as with the conviction that Jesus rose from the dead.

I should also note that there are some understudied demographic reasons (as opposed to theological reasons) why mainline Protestant denominations suffered the brunt of membership decline from 1965-2000.

First, the “white flight” to the suburbs that began in the 1960s decimated many urban churches, the majority of which were mainline denominations. Meanwhile, the non-denominational church appeared (and, eventually, mega-churches) and flourished in the suburbs, effectively creating a pipeline from mainline to evangelical that had more to do with a shift in population than with a shift in theology.

Second, there was/is an ongoing migration from the Northeast and Midwest, which were dominated by mainline Protestants, to the South and Southwest, which are dominated by Southern Baptists and other evangelicals (ignoring Catholicism). Again, this is a pipeline from mainline to evangelical that has nothing to do with theology.

In large part, the fact that evangelicals had been losing fewer members than the mainline denominations may be attributable to factors other than “sound doctrine and teaching.”

I appreciate your analysis, though the cynical part of me says that no matter what the data shows, it will always be interpreted the way the reader wants. For example, when I hear that evangelicals are growing, the response tends to be (from evangelicals) “Well of course – people are hungry for truth!” If it’s reported that mainline denominations are growing, I hear things more like “Well of course – people just want their ears tickled,” “It’s a reflection of our society moving away from truth,” etc. etc. Whichever way it goes, it’s easily explained away.

Yes and no. The question of why people are leaving can be answered, but the researcher has to ask the right questions of the right people. At this point, it’s no longer a question of which denominations are growing and why. The answer to that is none! But if we want to know exactly why people are leaving, we have to ask them, not the folks who remained and are just speculating about the departed.

Edit: I probably should re-emphasize that demographic shifts and their impact on evangelical church membership vis-a-vis mainline churches is an understudied subject. I am just saying that there are good reasons to doubt the long-standing evangelical explanation for that trend.

Yeah, that’s a really good point. That’s another area where we tend to see what we want to see.

I see little green men bringing bags of money to my door. Is that bad?

I’m going to say yes… but if they bring too much I can help you out.

So, I said up above that the study referenced in the Washington Post article went against the grain of most other research that I had seen. On the other hand, here is another recent dissenting voice: The Persistent and Exceptional Intensity of American Religion: A Response to Recent Research. These authors essentially argue that “intense religion—strong affiliation, very frequent practice, literalism, and evangelicalism—is persistent and, in fact, only moderate religion is on the decline in the United States.”

Interestingly, I saw one Culture War blog crowing about the results of this study: “But what about young people and all those millennial young adults who have stopped coming to church? Stanton cites a study that found that among young adults who have left their faith, only 11% had a strong faith in childhood. Conversely, 89% said that they came from homes with only a very weak faith and practice.”

I don’t know about you, but this sort of attitude sickens me. An entire generation is being lost, but it’s not “our” kids, so all is well. Ugh. I better not get started …

My aunt just sent me this article that had some interesting observations about the disconnect between Evangelical leadership (pastors, academics, and parachurch leaders) and people in the pews: Who's Really Leading Evangelicalism, the Shepherds or the Sheep?

[quote] Those evangelicals who lead denominations, para-church organizations, relief and mission agencies, who write well researched books, and publish editorials in The New Yorker may walk the halls of power but they are not the voices actually shaping popular evangelicalism. In fact, there’s growing evidence that even local pastors are having less influence on the evangelicals filling their churches. (…)

Despite an emphasis on the Bible and teaching in most evangelical churches, and despite the avalanche of resources offered via evangelical media and publishing, ordinary evangelicals are not being shaped by the orthodox views held by the elite evangelicals producing this content.

Furthermore, there’s evidence to suggest ordinary evangelicals are not adopting the views of their own pastors on key matters of doctrine either. (…)

So, the data suggests there are dramatically different sets of theological, cultural, and political views held by those leading evangelical institutions and those populating them. Of course, one should expect some distance between the views of leaders and followers within any group. After all, without a gap there is no where for leaders to lead.

However, the dramatic disparities now evident between elite and average evangelicals on politics, social issues, public policies, and even doctrine is alarming. It signals something much more disturbing and, I fear, unsustainable. It verifies the divide Michael Lindsay identified a decade ago, now, however, the gap may be so wide that it may be incorrect to call elite evangelicals “leaders” at all, because if no one is following are they really leading? [/quote]

The fact that there is a huge disconnect between Evangelical scientists and Bible scholars and the average Evangelical is evident all the time on these boards. Often times I feel like I am very middle of the road Evangelical because I read CT, I know what Ed Stetzer, Russel Moore, Mark Galli, and Tim Keller are writing about, I read books by Zondervan and NavPress and InterVarsity Press. But then I hear what the “Evangelical” view is according to Facebook or the news and I’m like, “Those people are not my people!” They evidently don’t really want me on their team either.

The way this relates to the topic at hand is just that I think its hard to attract new members and keep young people when your leadership is in the middle of a full-fledged identity crisis.

Hear! hear! The end of the article is worth repeating, as well:

As the divorce between elite and ordinary evangelicals becomes more likely, one question remains unanswered. Who will get the kids?

Unfortunately, that last question is both literally and metaphorically true!

Enjoyed the article, and agree with it for the most part. I see this in my home church, as our pastor is a moderate type guy who quotes Russel Moore, Scot McKnight and the like frequently, yet many in the pews are full on supporters of Franklin Graham, Jerry Falwell, Jr., Etc. Fortunately, there are also many who are not, but it creates a tension.

All that to say, there seem to be not just one “evangelical elite” but a separate “elite” of the media evangelical leaders whose influence leapfrogs the pastors and moderate seminary leaders into the pews. It makes for a difficult job as a pastor.

Say what you will about the millennial types, they are pretty intolerant of hypocrisy as they see it. Makes for a difficult time retaining them in church in the current climate.

Some points:

-

Although I’m on the other side of the globe, I don’t see “voting for Trump or not” is a doctrinal issue. The same things were said about Reagan and Bush, and many others before. I remember them being called ‘the antichrist’ and ‘Hitler’ etc. Now that’s all forgotten.

-

There seems to be a false dichotomy: either YEC or liberal. What if you’re neither? You can be TE and still believe the Trinity and Resurrection, that making disciples is literally The Great Commission, and that when it comes to missionary work - in the words of Rodney Stark - salvation should be more important that sanitation. Stark argued that when missionary work is reduced to social justice, you lose both social justice and disciples. Aim at heaven and get earth thrown in, aim at earth and get neither (CS Lewis).

-

The spirit of Protestantism is that we make up our own minds and read the bible for ourselves, which is probably why leaders don’t have as much influence. This can be both good and bad.

There is a lot of confusion in the States between politically conservative and theologically conservative. Of course you can be EC and not be theologically liberal or supportive of liberal politics. All of the mentioned “Evangelical elites” are theologically conservative. However, the direction political conservatism in the U.S. has taken is making a lot of Evangelicals (including people like my parents and my aunt who sent me the article, people who have been aligned with political conservatism most of their lives) very uncomfortable. And it is making them uncomfortable precisely because of “doctrinal issues” surrounding the responsibility of Christians to the poor, immigrant, elderly, sick, environmental stewardship etc. It’s one thing falsely to equate social justice with the gospel and another to deny that social justice has anything to do with the gospel or Christian ethics at all.

I am an Evangelical missionary, And our work is not just about social justice, it’s about evangelism and Scripture engagement and discipleship. And I am theologically conservative for the most part. But that doesn’t make me a conservative, especially not in the estimation of many of my fellow Evangelicals, some of whom would say I’m the most “liberal” person they know.

The problem is that people aren’t reading the Bible and making up their own mind. They are listening to pundits in a politically charged culture war, not their pastors, and they are picking up ideas that are flat out unorthodox, unbiblical, and heretical.

I feel very similarly to what you’ve outlined here… it seems like I’ve become a lot more liberal than I used to be, when I’m still fairly theologically conservative – it’s the unholy wedlock of political partisanship and Christianity that I find distasteful.

Channeling Newbigin here again …

Regarding the schism between the social justice folks and the evangelical gospel team (he may have used slightly different labels --but I think we’re on the same wavelength as to what that means…) He saw that as a very modern dichotomy that would not have been much recognized in, say, 1st century Palestine. For them, belief and obedience were one and the same thing. It was inconceivable (my strong word --maybe not Newbigin’s) that anybody could simply do some cerebral exercise of “believing” but then not live it. If you don’t live it (with all the social justice and verbal witness that this entails), then obviously you don’t believe it. He sites all the action words of Scriptures. People don’t just “believe” something. They follow.

On that reading the whole “social justice” vs. “good news of Christ” divorce of our recent generations has probably cost both sides more than they could afford.