You are assuming the 40 days is not just a round, theological number in Luke mirroring the 40 years Israel spent in the desert. You may claim he only appeared to his disciples for 40 days but we do know he appeared to a non-disciple Paul well after his reported ascension (40 days in Luke). So certainly a 40 day limit to the appearances of the risen Jesus to people can’t be true by Paul’s account. Unless we are somehow distinguish between bodily and spiritual appearances? I wouldn’t put much emphasis on the exactness of a special number in antiquity.

Your harmonization is not very convincing to me. It defies the plain sense of the text and is very counterintuitive from any storytelling standpoint.

Mark 16: 6 “Don’t be alarmed,” he said. “You are looking for Jesus the Nazarene, who was crucified. He has risen! He is not here. See the place where they laid him. 7 But go, tell his disciples and Peter, ‘He is going ahead of you into Galilee. There you will see him, just as he told you.’”

The simplest idea here is that Jesus will appear to his disciples in Galilee for the first time. Anyone reading Mark, this is what they would think from a narrative perspective. Thats the only reading that makes sense. And I say that fully aware that no one account is a complete record of events and John mentions only a singular Mary Magdalene but has a “we” in reference to the women. I can only presume this is the sense of what Mark means to narrate.

In Matthew 28:5 The angel said to the women, “Do not be afraid, for I know that you are looking for Jesus, who was crucified. 6 He is not here; he has risen, just as he said. Come and see the place where he lay. 7 Then go quickly and tell his disciples: ‘He has risen from the dead and is going ahead of you into Galilee. There you will see him.’ Now I have told you.” This is on the sabbath in the morning.

Again, the same as Mark. An angel tells the women to go tell the disciples to go to Galilee where they will see Jesus. This is narrated as if it is where the disciples see Jesus for the first time. Then a little bit later Jesus appears to the women and tells them the same exact thing: "Do not be afraid. Go and tell my brothers to go to Galilee; there they will see me.”

This again is clearly narrated as if the disciples will see Jesus for the first time in Galilee. It is incoherent otherwise. Matthew 28:17 has the disciples seeing him but some are doubting. This doesn’t sound like a host of Jerusalem appearances and explanations have happened–it sounds like a first appearance. You might say its understandable for the disciple to be so nervous as seeing a dead man rise but the only people harmonizing these accounts are the ones who think they are all true. Under that pretext, these disciples already saw Jesus raise the dead, walk on water, control the weather, the sky went dark in the middle of his crucifixion, he fed 5000 people with a few fish and bread and performed a host of miraculous healings. If he already appeared to them a few times in Jerusalems, this is an odd reaction. Especially when they expect him on orders from the women. This type of exegesis would convince you 99% of the time on every other issue and would certainly be used to explain away errors.

It is clear in Luke 24 that they see Jesus in Jerusalem for the first time. The tomb is empty, Peter sees the linen then Jesus appears to two disciples on the road to Emmaus. Finally they recognize him at a home and they rush to Jerusalem to tell the disciples its true Jesus has risen. Recall that Luke 24:13 shows this is all on the SAME DAY. The two disciple immediately rush to Jerusalem and tell the disciples who are now startled as Jesus appears to them.

John 20:19 also has Jerusalem appearances: “On the evening of that first day of the week, when the disciples were together, with the doors locked for fear of the Jewish leaders…” A week later, because Thomas was missing, Jesus appears again to the twelve.

Galilee is too far from Jerusalem to assume Jesus could have appeared to his disciples first in both locations on the same day. The plainest sense of Matthew and Luke indicate Jesus first appeared to his disciples in Galilee. Luke shows no awareness of any Galileans appearances. Matthew and Luke also show no awareness of Jerusalem appearances to the disciples. John 20 shows a Jerusalem appearance to the disciples (two as Thomas is not there the first time). Original John shows no knowledge of Galilean appearance stories. John 21, the second ending, which was added later by a redactor has Galilean appearance stories.

You have to read and understand the text in a bizarre way to avoid errors. Basically, you have to want the text to not have errors. You have to have inerrancy, the theological anti-virus software running in the background of your mind forcing you to come up with any logically possible solution to these discrepancies, to the point where you have to reject the plain meaning of what scripture says. Also, how does one explain the complete lack of Jerusalem experiences in Mark? I mean, if this was actually based on Peter’s preaching, wouldn’t Peter talk a lot about the appearances of the Lord over 40 nights? Wouldn’t the resurrection of Jesus be a central point of Peter’s preaching? Likewise, wouldn’t the apostle Matthew record details of both the Jerusalem and the Galilean traditions, being that he was eyewitnesses to both? How on earth, under traditional authorship, does one find two such diverse streams of tradition in the gospels? We could include original John (ending at chapter 20) in this as well. No to mention Luke has the text of Mark in front of him but chose to omit this line. Its quite plain that Luke has a theological geography here. The appearance of Jesus and ministry of the apostles starts in Jerusalem and slowly spirals outward ending with Paul preaching in the capital of the world, Rome. That is not history, its theology. The simplest solution is that there were two sets of appearance traditions floating around. The redactor of John added 21 bringing both together in his gospel.

Paul’s list adds a complication as Jesus appears to Cephas first and then to the Twelve but there were only 11 per the gospels account of Judas’s betrayal, unless Paul is unaware of that tradition, which if historical, would seem odd.

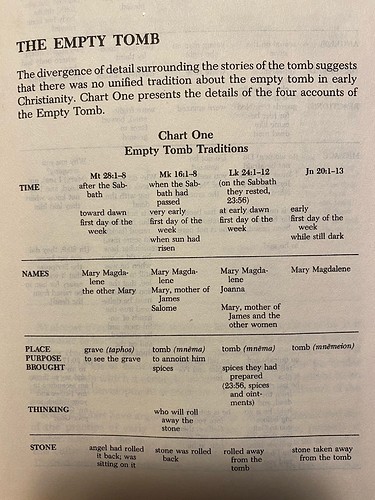

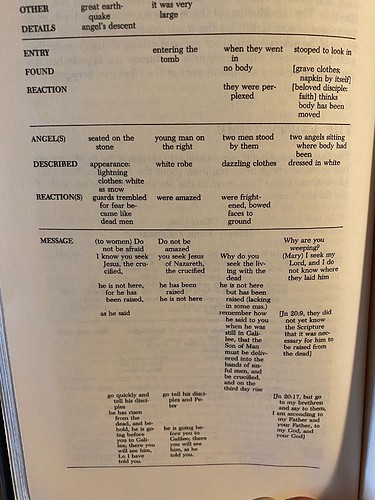

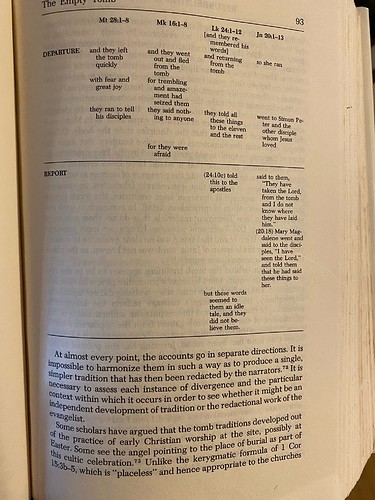

Not to mention , there are a host of other discrepancies between the accounts (time they went, the stone etc., some of which can be reconciled and some which cannot and most of which are minor but are discrepancies none the less. I’ll post screenshots of a table from Pheme Perkins’ book Resurrection New Testament Witness and Contemporary Reflection