I think many therapists already view religious practices as “another helpful therapy,” and if so, it won’t hurt and might help. As far as “the same results” goes, until we understand the brain better and have a more nuanced approach to scanning, i think they will look the same. But you have to remember that not too long ago researchers said DNA of male nonhuman primates had more in common with human male DNA than with human female DNA. We are still in the very crude stages here.

I think it implies that free will (or our cognition and even subconscious generally) can be trained.

I’ve heard emergency personnel remark during emergency response trainings that in any event that takes you way outside your normative experienes (much less your ‘comfort zone’) will immediately reduce you to whatever training you’ve had. You won’t be a sudden hero. You won’t brilliantly think of something on the spot and disarm some hostage situation with your sudden burst of wit. No … you will witlessly and pathetically go into panic mode, and the only thing that has a chance of even breaking through any of that is your training (if any) that’s been drilled into you as some sort of automatic response. In short: You fall back on your training.

This matches well what I’ve heard a social psychologist (J. Haidt) observe - and that is that your cognition is only the tip of the iceberg of all your mental activity. It isn’t that you have no say over all the rest of it. But that part will probably only respond to repeated training until something has turned into a habit for you. Our brains relieve us (thank God) of most of what needs to be done in a day, freeing us up to think about those few higher things that we want to give conscious attention to. I was riding to school on bicycle yesterday, - a route that for me involves a main path, and then also a slight deviation off that main path for part of the way if I want to be off the highway for a bit. I found myself at school and was shocked to discover that I could not remember which of those two paths I had just chosen only minutes earlier! My mind had been on other things, and my navigation brain was on autopilot - and did just fine, of course.

Does that mean I had no free will about my ride? Of course not. It just means our brains are amazing things. And that it matters what we fill them up with over the years. Because what goes in, eventually comes out. I.e. You may not feel like you made a choice about a given thing in that sudden given moment, but in reality you cultivated a brain that led up to the choice that was made - and your brain followed that set course.

It isn’t for nothing that the Bible exhorts us to meditate on good stuff - and to have God’s word daily about us. James K. Smith is exactly right that we need to pay attention to what the liturgies of our lives are. Because either you choose those. Or the culture you’re in chooses them for you.

Why pathetically though? There’s nothing pathetic about good training and practice, good habits, instinctive reaction and muscle memory.

The words are a hard poke at any fantasy we may harbor that we will somehow “rise to the occasion” when faced with stuff we’ve never faced (or been trained for). 99% of the time … we won’t.

It isn’t a knock at training. Quite the opposite: It’s an affirmation of our need for it. So those words convey exactly what I intended about our fantasies of spontaneous heroism.

Got it. I was reacting to it in the narrow context. It’s not fantasizing though (although it may be ; - ) to mentally practice reacting to things properly, how you should and would respond in different scenarios.

A common experience among those driving the same routes repeatedly. Sometimes driving one part of the trip on a familiar route has initiated the following of the automatic track even when my purpose was to get somewhere else - maybe I drive too often thinking other matters.

One professional truck driver even said that he could drive his usual route eyes closed, from start to end. A bit scary scenario, goes well until a child or moose suddenly jumps on the road. At least, not responsible behavior. I guess we have enough of free will to choose a more responsible approach.

That would be hyperbole on his part since that wouldn’t actually be possible. But … point well-taken nonetheless. In fact ‘open eyes’ and auto-pilot responsiveness just goes to show how powerful that function really is for us. Because despite my initial unsettled feeling that I hadn’t been paying attention at all (did I run any red lights? … would I have hit any obstacles that suddenly crossed my path?) … despite an initial concern; I’m actually quite sure my ‘autopilot’ attends to all those things just fine. For one thing - if it didn’t - I wouldn’t still be alive right now, as many thousands of miles as I’ve biked while in preoccupied thought. Any bicyclist truly inattentive to their surroundings will not remain in this world long. (Or if operating motor vehicles or heavy machinery then it is also the unfortunate people around them who may not be long for this world.) The point is - that our ‘autopilot brains’ are still extraordinary exemplars of interactive attentiveness - with every one of our fully operational senses.

Programmers of AI (or self driving cars) … can just continue to look on in envy. It would appear they have yet to match what a human brain can do even just ‘idling’ on autopilot. And were an obstacle or motorist to infringe on my path while in such a state, I know my ‘autopilot brain’ would quickly rouse my full brain to immediate attention. I know this because it’s happened before.

I read or heard recently that driving is the most complex single task that we do. So yeah, safe autonomous vehicles aren’t quite there yet.

Gravity is not always a factor which we can adequately compensate for, however. I used to commute to work on my bike (5 miles one way), and after I retired I would make a 6 mile round trip (sometimes a couple miles further) pretty much daily on a lovely hike and bike trail, now paved, along a canal.

Once when I left the pavement to pass some pedestrians by going on the grass, gravity dictated that to keep my balance I should turn somewhat to the left. Problem was, the concrete was slightly higher than the turf and it dictated my not turning left. Gravity changed its demands at that point and not too gently suggested that I land on my palms on the concrete, the result breaking the scaphoid in my right wrist. I am now more ambidextrous than I was, having a good while learning to use my left hand a lot. ![]()

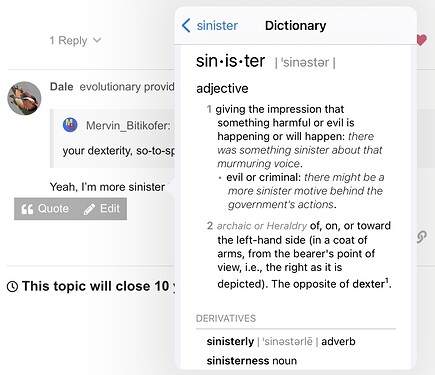

We could exchange our bicycle mishap stories sometime! I’m glad you survived yours, though it sounds like it was a memorable one with lasting impact on your dexterity, so-to-speak! ![]()

Sounds true because I have experienced similar type of situations. Sometimes there are also semi-automatic responses that appear to happen faster than the brains can understand what happens.

Once there came an obstacle to the road when I was driving in poor conditions (dark night, rain, partly blinded by the lights of other cars, speed above 80 km/h). The only thing I remember was a flash of a plastic bag in front of the car before my semi-automatic reactions took over. My brother was driving behind and saw the situation. A drunken woman with a plastic bag suddenly stepped to the road in front of my car. He thought there was no way to avoid a crash. In a rapid move, my car dodged the woman. I do not know how much it was because of my semi-automatic responses and how much a miracle but I was very thankful to God for the narrow escape. The woman would probably have died or injured badly if she would have collided with the car.

Self-driving cars may react faster than humans but the sensors demand suitable conditions, otherwise the cars are blinded. There is still much work to do before self-driving cars are truly safe in the real world.

Apparently, folks still haven’t figured out how to get them to understand what kangaroos are doing. The fact that they often detect heavy rain as “I am driving through a solid” is probably more of an issue.

How do morality, spirituality, and love interact? Please try to figure out that one.

Nope, brain scans cannot prove anything (it’s sometimes comical when reports imply that they can). Since we’re in the business of greater understanding, brain scans could be quite useful for examining correlates, which could include behaviors. I wish there were MORE of this research!

Brain scans detect electrical activity right?

If there is none at all you would be dead right?

So there is some activity beyond our conscious control. That must be the baseline for any further deductions.

The peace of God would mean that you have deliberately stopped worrying, thinking, obsessing, all the conscious thoughts. So, in theory you could tell the difference between a person who is worrying and a person at peace by the amount of brain activity over and above the baseline.

Why am I wrong?

Richard

Other than a recommendation for Neurotheology, I didn’t learn much. We have known for a relatively long time that what we think and do has an effect of the physiology of the brain, which obviously includes meditative and contemplative practises. It also only shows how the brain processes rather than providing a deeper understanding of consciousness. For me, experiences, whether religious or not, are internal and what brain scans do is measure the external appearance of those internal experiences.

The work of Iain McGilchrist, or eve Bernardo Kastrup, seems to me to provide a more insightful look at how the brain is processing information and stimuli from the senses, and where we suddenly find that empiricism breaks down, suggesting that the materialist perspective that our bodies generate consciousness is no longer viable. Even memories are impossible to locate. Rather, the hypotheses of these people (and others beside) moves towards consciousness being primary, and our experience of consciousness is a localised part of the larger field of consciousness, which you could call God.

What is of importance is how we habitually process the input, and McGilchrist suggests that this is influence by which hemisphere we give dominance to. Both hemispheres work together in extremely complex ways of course, but our focus seems to be dominated either from the left hemisphere or the right, giving us two different directions of behaviour. The one narrowly focussed on detail, and the other having a more wider scope, into which it seems the healthy individual would integrate the narrowly focused details. Both indicate that problems arise when we are too focussed on the narrow perspective, and Kastrup “diagnosed” his former self with a kind of intellectual fundamentalism, out of which he has emerged to grasp the wider connection of things.

McGilchrist, rather reserved in his expression, has a similar position, but both find that humanity has habitually narrowed its perspective, producing ultra-atheists and ultra-religionists in contraposition, each stuck in literal and dogmatic positions. The truth, it seems, is in the wider perspective.

This is (from my non-authoritative, non-expert perspective) key to understanding what we can and cannot learn from brain scans. As technology improves, scanning can refine what we can learn, but even so, causal links are ever elusive.

It’s worth quoting John Tyndall here: “Were our minds and senses so expanded, strengthened and illuminated as to enable us to see and feel the very molecules of the brain, were we capable of following all their motions, all their groupings, all their electric discharges, if such there be, and were we intimately acquainted with the corresponding states of thought and feeling, we should be as far as ever from the solution of the problem. How are these physical processes connected with the facts of consciousness? The chasm between the two classes of phenomena would still remain intellectually impassable.”

Maybe he was wrong, but I think he was right.

I agree, but I think that it would be more applicable to this statement: