If you want a more nuanced view, I regard most of the Pentateuch as pre-exilic, but Genesis 1-10 as exilic at earliest. See here for my reasons.

Hmm? I have already said that the written language of Sumer survived all the way until the first century AD. What I was saying that has zero evidence is the transmission of any Sumerian words or names into the Hebrew Bible. Indeed, as far as I’m aware, there isn’t a single word or name in the entire Hebrew Bible borrowed directly from Sumerian. This is in stark contrast to the amount of Egyptian words and names we have in the OT. Anyways, you were right, I guess I have to do a little more appreciating for the ‘correlation’ between the Sumerian ms and Moses. Back to this at a later point.

Regarding the Ketef Hinnom inscriptions (silver scrolls), you said;

This is actually the time frame we would expect to find the “raw material” for an Exilic “edit” of the “old religion” of Judah.

I simply don’t understood the connection you’re making here. How exactly are the Ketef Hinnom manuscripts ‘raw material’ for exilic editing of the Pentateuch (especially if, as per your view, the Pentateuch didn’t exist yet?)? It seems to me as if the silver scrolls are just like any other manuscript of the OT, except earlier. They certainly reveal that the Pentateuch, in some portion, was around in the pre-exilic period. So, questions I would have include the following: Who wrote Numbers 6:24-26? How much else of the Pentateuch was this figure responsible for writing? And when did he write it? Something else I found uncertain was this:

In the 1800’s David Roberts found a hidden entrance to a tomb under the snake carved on the roof of the squared outcropping. And inside the tomb, when they dug it out, there was no body, but there was a black painted rod… buried in the tomb, with a hidden entrance, under a giant carved snake. Draw your own conclusions.

I tracked down the picture you gave for this carved snake, and I found it was simply a blog travelling site and provided me no information about the carving itself. I found David Roberts Wikipedia page, and the entry mentions nothing of this finding either. Is this finding relevant at all? Before I can say anything of the like, I’ll need to know the location of the carving and its dating. Finally, I finally took to searching up the Sumerian word ‘ms’ to investigate it for myself. However, I found no results. So, I tracked down the Pennsylvanian Sumerian Dictionary, and enterred the word ‘snake’ to find the Sumerian word ms. And I found it. And there is something very startling here.

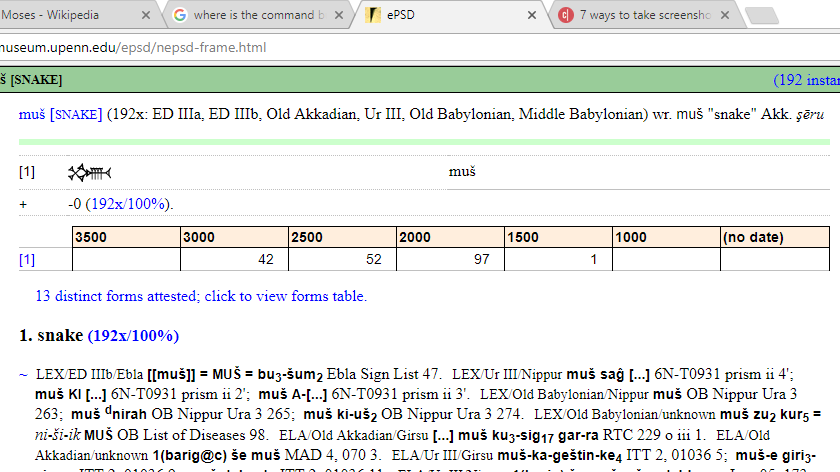

The Pennsylvanian Sumerian Dictionary (PSD) is a terrific resource. It actually lists every usage of each Sumerian word, ever, and how many times it was used in a every 500-year period of time. I’ll simply reproduce the chart the dictionary gives for the usage of this word over time;

I’d recommend going to the article on the dictionary itself: http://psd.museum.upenn.edu/epsd/nepsd-frame.html

As you can see, the Sumerian muš was first used in the period between 3499-3000 BC, where it has 42 occurrences. Then, 2999-2500 BC, it has 52 recorded occurrences. Then, in 2499-2000 BC, it has 97 recorded occurrences. It seems to be increasing in use. However, all of a sudden, between all of 1999-1500 BC, there is only a single recorded occurrence of this word, and from 1499-1000 BC, the period when Israel was founded, it was not used once in Sumerian writing, and was never used subsequently. In other words, it looks as if the Mesopotamians had entirely stopped using and knowing this word at this point. Yet, your theory holds that not only would someone in Israel have known how the Sumerian language works, but they would have in fact known about this word and had specifically drawn from it when naming Moses. That sounds like quite a stretch to me, and I’d hate so sound like a broken record, but in this exact time period, the Egyptian language was thriving throughout the Levant like no other foreign language and the word mose was still being used widely. This new finding of mine, in my view, provides another serious setback to any claim that Moses name is of Sumerian origins, rather than of Egyptian origins, the position of most scholars in the field.

Thanks, that was an interesting examination, although I’m not personally convinced.

Feel free to point out any flaws in the reasoning and account for the facts in a different way.

Your examination is not flawed at all, it’s just that it isn’t the only available explanation. Indeed, your argument is rather good; the only OT references to the primeval history in Genesis (ch. 1-11) suddenly appear during and after the exile, which may indicate that this, or the period slightly earlier, is when they were composed. That reasoning works, but that isn’t the only explanation in town.

Firstly, your argumentation doesn’t rule out a pre-exilic dating of Genesis 1-11, simply because, by the same reasoning, I can posit that Genesis 1-11 was composed some time in the century before the exile (700-600 BC), and in the time afterwards and during the exile, these texts gained authority and they started getting quoted. Indeed, your argument would only rule out a dating significantly earlier than the exile. If I were to posit a dating of the primeval history in, say, 650 BC, it would fit fully well with the facts you’ve outlined.

Secondly, there are other possible reasons why these books wouldn’t be quoted until some exilic or post-exilic period of time besides that they didn’t exist. One explanation is that OT books, in general, appear not to quote each other at all until the exilic and post-exilic times. Why? Well, before the exile, the kingdom of Judah remained a nation (Israel was wiped out by the Assyrian in ~700 BC), however, after the exile, the Jewish people truly lost their independence in its entirety for the first time. How could God have chosen the Jewish people for this land if they had lost their exile? This may have been the reasoning, indeed, not only had they lost indepence but the Temple was destroyed. This might have spurred the Jews to begin starting to look back at their earlier predecessors and traditions and begin viewing them with more authority, and begin clinging to them more in order to give them hope and perseverance despite the fact that they’ve been entirely conquered. In other words, it could be that during the exile and later periods, the Israelite’s began taking their traditions more seriously and importantly.

Secondly, we may have archaeological evidence indicating a maximum dating for the entire Pentatuch by c. 600 BC. This archaeological data was only published last year (2016) in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences by Israel Finkelstein among others. This research demonstrates, with new archaeological data, that literacy in Judah was much higher than previously thought in the 7th century BC, and therefore, would set the stage for the major compilation of biblical texts. In other words, I find c. 600 BC to be a good maximum dating for the Pentateuch (and DtrH), and therefore I’d place the compilation of the Pentateuch anywhere from the 10th-6th centuries BC (basically from when Israel became united until the exile).

Ok, what do you think explains all the evidence better?

But that wasn’t the only piece of evidence I presented. I presented multiple lines of independent evidence.

- Certain vocabulary in Genesis 1-3 is used elsewhere only in books written during the monarchy or later. A couple of terms in Genesis 1-3 are found in Sumerian literature, though they are not found anywhere else in the Bible.

- Certain names appear only in Genesis 1-11 and books written during or after the Babylonian exile.

- Some names appear as personal names before the exile, but as place names only during or after the exile.

- Some verses in Genesis 1-11 use place names which help date the text. In particular, several verses in Genesis 10 indicate the chapter could not have been written until after the reign of Solomon.

- The text of Genesis 1-11 has a number of strong literary parallels with various Mesopotamian texts which were written very early, long before the birth of Moses. These texts were not available to the Hebrews until the exile.

- None of the genealogies from Genesis 12 to the end of 2 Kings go back any further than Abraham’s family.

- None of the books from Genesis 12 to the end of 2 Kings show any knowledge of Adam, Eve, the garden, the serpent, the fall, Cain and Abel, the flood, or the tower of Babel, the sabbath memorializing the creation (Moses explicitly says the sabbath memorializes the exodus from Egypt), or any of the events of Genesis 1-10. It’s not merely that these chapters aren’t quoted, it’s that most of the Old Testament shows no knowledge of them at all.

There is a lot of data there to be explained, and I don’t think a composition date in the seventh century does this efficiently.

How does this explain why none of the books between Genesis 12 to the end of 2 Kings show any knowledge of Genesis 1-10? Are you saying that for over 1,000 years, those chapters of Genesis were known but weren’t “taken seriously”?

I have read that article. It’s great, but it doesn’t present any evidence that Genesis 1-10 were written before the exile. Nor does it even argue that. In fact one of the authors, Finkelstein, believes that the composition of Genesis “continued into the Persian period, until at least the fifth century B.C.E.”, way past your own “maximum dating for the entire Pentateuch”.

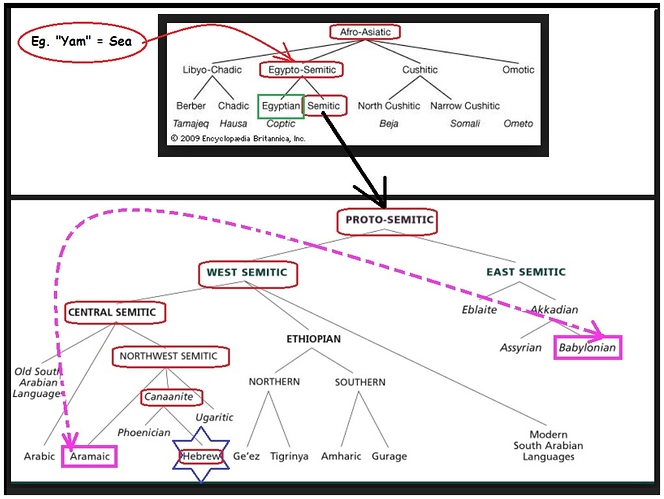

Firstly, while you want me to place Sumerian on the same etymological level as Egyptian - - I would suggest that the proper comparison between Egypt’s influence on the Bible is the role that parts of the Afro-Asiatic linguistic tree had on the Bible (the Babylonian of the East Semitic branch combined with the Aramaic of the Northwest Semitic branch):

Most people are not aware of the older connection between Semitic and Egyptian language. The “unity” between them came at a time when the northern coast of Africa enjoyed more temperate weather and vegetation. Words like “yam” were shared, and meant “ocean” or just “big water”. And when the desert divided northern Africa and the Levant into isolated pockets of humanity, divergence in the language followed.

The fact Sumerian is an isolate, and nowhere on any of these linguistic branches, should pretty well explain why Hebrew priests had little intention of parading their knowledge of foreign languages around, unless required by the topic.

You say there is " zero evidence is the transmission of any Sumerian words" - - well, this is what we are disputing, right?

You seem to be implying that my proposal can only be true if Sumerian words are casually found in the Bible as well, to corroborate my proposals about “Edom”=“Iddim” and “Cherub” “Ker”-“Ub”. I think in both these cases, the etymologies I have outlined make more sense that the traditional explanations. Would Jefferson just randomly sprinkle Greek into his proclamations when he can use all sorts of French words that people know?

Why would a Hebrew scribe make casual use of Sumerian pronunciations, when everyone who could possibly know cuneiform is more familiar with the Semitic/Akkadian pronunciations? And yet, ironically, I do think the scribes unwittingly did just that when they coined the word “Cherub”; for 2000 years, Bible scholars have been looking for the perfect answer to where that word comes from. And they are still debating it, because they haven’t gone back far enough - - to Sumerian, kept alive by the Babylonian priests.

But Lo! @ManiacalVesalius, I think there is one example of exactly what you are looking for from me - - the use of Sumerian that seems obviously Sumerian, but has been purposefully veiled. You may have skimmed right over this particular verse in Isaiah with Yahweh doing the speaking:

Isaiah 54:9 “For this is as the waters of Noah unto me: for as I have sworn that the waters of Noah should no more go over the earth…”

In 54:10, we get the following clarifying comments:

“For the mountains shall depart, and the hills be removed; but my kindness shall not depart from thee, neither shall the covenant of my peace be removed, saith the LORD that hath mercy on thee.”

What an interesting euphemism! “… the waters of Noah…”! How puzzling! Certainly the waters that swept away life forms by the thousands are not Noah’s at all … but Yahweh’s waters! Noah had to contend with them. Noah had to build an Ark. We could say the Ark is Noah’s. But can we really affirm the phrase “Waters of Noah”?

As you know, the pagan ANE awarded the waters of the world to the care of the Sumerian deity, Enki, later to be renamed Ea, by the Semitic Akkadians. Written in cuneiform, Enki is a two-syllable word: “(e)N K(i)”, where I have put the vowels in parenthesis.

When considering the flood stories originating out of Sumerian, Akkadian and Babylonian literature, I have marvelled at the diversity of the names of the “hero figure” who builds the boat that saves a human remnant from drowning:

One name is:

1] Ziusudra = Sumerian: 𒍣𒌓𒋤𒁺, lettered ZI.UD.SUD.RA2 or pronounced Ziudsuřa(k) “life of long days”;

[Note: Recorded in Greek as: Ξίσουθρος Xisuthros. A late version of The Instructions of Shuruppak refers to Ziusudra.]

2] Zin-Suddu of Shuruppak = Sumerian: 𒍣𒅔𒋤𒁺, lettered ZI.IN.SUD.DU

[Note: listed in the WB-62 Sumerian king list recension as the last king of Sumer prior to the deluge. He is subsequently recorded as the hero of the Sumerian flood epic. He is also mentioned in other ancient literature, including

The Death of Gilgamesh and The Poem of Early Rulers.]

3] Akkadian Atrahasis (“Extremely Wise”);

4] And the Akkadian Utnapishtim (“He Found Life”).

5] And lastly, of course, we have the Biblical hero of the flood story, whose name in English is Noah.

In Hebrew, Strong’s Hebrew # 5146, but not pronounced “Noah” in Hebrew - - but:

Pronunciation

No’ - Akh

Why should the hero’s name be Noah? It doesn’t look anything like the earlier names assigned to this hero. Certainly this is evidence that Biblical dependence on the pagan literature is more flawed than I admit?

It’s a name that is supposed to be derived from the word for “Rest”. Why would the puzzling phrase “Waters of Noah” even appear on the pens of those who wrote Isaiah?

But don’t you see it? The phrase is actually “Waters of No-Akh” ! And in writing, the semitic practice of writing just the consonants seems to tell us the whole story:

“The Waters of N(o)(a)K” < < For centuries years, scribes trained in cuneiform have been reading this Sumerian myths that presented the world from this view . . . but more like this:

“The Waters of N.K.”!

Now this sentence makes sense. For Sumerians, the world’s waters have always belong to Enki, and then they became “the waters of Ea[/Yah]”.

I’m not sure you are the person we need to convince. There are always those content with the status quo explanations.

Jonathan’s full catalog of justifications is certainly quite extensive. And you have acknowledged the logic of some of his assertions. For other readers, I provide two paticularly good paragraphs:

Jonathan and I differ on the Pentateuch. He says he thinks it is mostly pre-exilic, while I think the reverse. The “fabulous” nature of much of the Patriarchal material seems more in keeping with the Hellenistic (or even Persian) taste for the “fantastic”. The Wrestling with God story is about as dramatic as it gets, where the hero is certainly wrestling with a deity just minutes before he assumes his duty as the rising sun. At its heart, it is a pagan pre-exilic story, that gets a new dressing when the Persian-inspired scribes get to it.

Leviticus, part of the Pentateuch, has lots of Persian parallels in terms of “clean” and “unclean” practices. Exodus presents the Levite priests as wearing cut-off trousers as part of their elaborate priestly garb. Nobody in the ANE had anything like what the Levites wear - - except the long-legged trousers of the Magi.

The use of the Strong’s Hebrew #1270, barzel, for “iron” is also very convincing. Used at least 73 times in the Bible,

But more than 10% of them are in Deuteronomy… which is supposed to be even before the beginnings of the Iron Age most anywhere in the ANE. Deuteronomy 4:20 even says God refers to Egypt as an “iron furnace” of trouble to the Hebrew - - at that time a fairly unlikely use of that term for Egypt.

Leviticus and Numbers, have 3 unlikely uses of the word:

Leviticus 26:19 refers to a changed world, where the Earth is as brass and the Sky is as Iron.

Numbers 35:16 spells out the specifics of capital punishment if someone dies: “If he smite him with an instrument of iron, so that he die, he is a muderer…” I wonder what the fellow is if the man is smited with a brass tool? Clearly this text is written at a time when nobody even remembers using tools of brass, instead of the now common tools of iron.

This is easier to see than in the example of Numbers 31:22, where the list of things that will survive fire includes “the brass” and “the iron” things.

Genesis 4:22 is wildly out of place naming Tubalcain as an instructor “in brass and iron”. If he was the instructur in working iron, his students all quit doing so as soon as he died.

Looking at your seven pieces of evidence, not all of them argue for an exilic or post-exilic date. Point 1, for example, notes that the vocabulary in Genesis 1-3 is used elsewhere “only in books written during the monarchy or later”. Well, for one, the monarchy was founded c. 1000 BC. Secondly, we don’t have any books predating the monarchy, so who is to claim that this vocabulary didn’t exist before then? We certainly don’t have a biblical book dating to the 11th century BC to show us what pre-monarchic vocabulary looked like.

Point 2 is similarly weak. Again, just because not every name in the entirety of the Pentateuch is attested in an extra-Pentateuchal source until the exile or after doesn’t at all indicate that those names weren’t around at the time. What’s worse is that we simply don’t have many texts outside of the Pentateuch written in the pre-exilic period in general (there’s Amos, 1 Isaiah, and a few others), and so we really don’t have a large sample of names at the time to say which names did or did not exist before the exile.

Most of your other points suffer from this as well. Point 4, if true, helps date the Pentateuch after the reign of Solomon – but that’s c. 930 BC and later, this hardly proves that the Pentateuch was written after 586 BC (date of exile). I also find point 5 confusing – whose to say that the Israelite’s didn’t know about the Mesopotamian near eastern stories until the exile? What evidence is there for this?

As I said earlier, most pre-exilic documents don’t quote earlier ones in general, this isn’t exactly an exception with the Pentateuch. Anyways, after looking at this a little more, there seems to be another problem with this argument. That is to say, only four books of the Old Testament are pre-exilic, besides the deuteronomistic history. Those are Amos, Hosea, Micah, and ch. 1-39 of Isaiah. The first three are extremely short in length and so it’s not problematic that they don’t refer to Genesis 1-11. Isaiah 1-39 doesn’t reference Genesis, but neither does Isaiah 40-66, written during and after the exile. So it’s not surprising at all that we don’t find references to Genesis 1-11 in these books. The Deuteronomistic History refers to the Sabbath system, where the Israelite’s work for six days and then rest for one, which is arguably based off of the creation week in Genesis 1.

So really, in the end of the day, the argument makes sense, but it’s not very convincing. It’s heavily reliant on the fact that we have very little pre-exilic material to work with, and the argument tries to point at holes in our understanding of pre-exilic Israel and say “uh huh, there’s something missing that should’ve been there otherwise!” Sorry, but I’m not personally convinced.

We have a range of texts showing us what pre-monarchic vocabulary looked like. For a start, we know it wasn’t even Hebrew. We know that Genesis 1-11 uses vocabulary which didn’t even exist before the late monarchy, and it has an abundance of exilic vocabulary. I’ll write more later, but you need to deal with the facts in the text.

The fact Sumerian is an isolate, and nowhere on any of these linguistic branches, should pretty well explain why Hebrew priests had little intention of parading their knowledge of foreign languages around, unless required by the topic.

Well, that doesn’t particularly make sense, since the Hebrew priests wouldn’t have known Sumerian to begin with. And, since Sumerian is so isolated, doesn’t that yet again help in showing that the Hebrews simply wouldn’t have known anything about reading it? In the 7th century BC, Ashurbanipal, one of Assyria’s last emperors, bragged about being able to read the difficult Sumerian language. There was no educational system in Judah that could have possibly educated people in the Sumerian language, meaning there was no education in Judah at all in the Sumerian language, which seems to imply know one knew it. After the fall of Sumeria itself, the study of the Sumerian language was usually reserved for Babylonian schools interested in studying their ancient traditional stories (such as how a modern American might engage in the study of Hebrew to be able to read the Old Testament). There was, in contrast, no such thing in Israel. There was no mechanism for an Israelite to actually learn the Sumerian language. There is not one Sumerian inscription to ever have been discovered in Israel. Why? For the same reason there aren’t any Sumerian inscriptions in the land of the Philistines – no one could read it and there was no one to tell them how. This provides another significant reason, which I have not touched on before, to continue showing why Moses is not of Sumerian etymology.

I’d also hate to sound dismissive, but Noah is certainly not of Sumerian etymology. A quick check with Strong’s Hebrew Dictionary reveals that the origins of the name Noah (no’-akh) is already known. It’s derived from the Hebrew word nuach (noo’-akh) which means ‘rest’ or ‘repose’.

We have a range of texts showing us what pre-monarchic vocabulary looked like. For a start, we know it wasn’t even Hebrew. We know that Genesis 1-11 uses vocabulary which didn’t even exist before the late monarchy, and it has an abundance of exilic vocabulary. I’ll write more later, but you need to deal with the facts in the text.

I was actually thinking of mentioning that, since I think it fits better with my position. Hebrew did not appear out of nowhere, it gradually evolved from other Semitic languages, and most of the vocabulary in Genesis 1-11 seems to be at home with the vocabulary of its preceding Canaanite/semitic languages. There certainly is no evidence to show that certain vocabulary in Genesis 1-11 only appeared during and after the exile, otherwise you haven’t mentioned this evidence. I don’t think the silence of our very small corpus of pre-exilic literary works attests good evidence for this claim.

Can I ask what you’re basing this on? We have a range of evidence for this. I cited just some of it. This isn’t an argument from silence, it’s an argument from direct evidence.

I mean, I don’t know if you provided much direct evidence at all. As I understand it, the argument goes like this: in our pre-exilic biblical books, certain vocabulary words are not attested that are in Genesis 1-11, but these are then mentioned in our exilic and post-exilic works, and so Genesis 1-11 is an exilic/post-exilic work. By that very logic, if I find a handful of vocabulary words in the entirety of Genesis 12-50 that don’t appear in our few pre-exilic works, I could use this same argument to claim that Genesis 12-50, too, is exilic/post-exilic. I’m sure neither of us would be willing to accept this argument.

If you could demonstrate that some vocabulary in Genesis 1-11 didn’t exist before the exile, then that would be something else. However, an argument from silence can’t demonstrate that. This is why I say that your argument might give an indicator, but definitely not a proof or serious evidence for why we should date Genesis 1-11 to the exilic/post-exilic period. In my view, I date the Pentateuch to the pre-exilic period since I can find a large number of traditions in this work that originated in the pre-exilic period, some of them unknown in the exilic/post-exilic period. I’m not sure if I have any specific proof from Genesis 1-11, though.

Something that most of us will have to come to is that there’s no serious evidence, one way or another, to be able to date Genesis’ primeval history. We can make tentative estimations at best. I think this is something we’d be able to agree on.

I think your first 2 sentences are “dogs that don’t hunt.”

Scribes taught to write Cuneiform were taught the Sumerian pronunciations, as well as the Akkadian/Babylonian pronunciations.

It’s not very different from “sacred process” we put our seminary students through (for centuries?) when we teach them Greek. They learn the names of the Greek letters. They learn the sounds of them. They learn what the Greek words sound like in the LXX. And they learn what they mean when translated into Latin.

No that is not the argument. That is only one small part of the argument. I posted a seven point argument, and you’re only referring to one point.

But that’s not the logic being used. You’re not addressing the other six points of the argument.

But it’s not an argument from silence. We know when certain words were formed. We know that Hebrew progressed through various stages, from proto-Hebrew/paleo-Hebrew (no earlier than the eleventh century), to archaic biblical Hebrew (tenth century to the sixth centuries, until the exile), then to standard biblical Hebrew (eight to sixth centuries), then late biblical Hebrew (fifth to third centuries). Over time the script changed, the vocabulary changed, the grammar changed. Texts written in different forms of Hebrew can be differentiated from each other by virtue of the characteristics of each written form.

What you are arguing is like saying that a book which uses words like “refrigerator”, “internet”, “TV”, “radio”, “Soviet Union”, “Barak Obama”, and “global warming” could have been written 300 years ago, because lots of the other words in the book are words which were used 300 years ago, and it’s just “an argument from silence” to argue that these words weren’t used before the late twentieth century. This is directly analogous to Genesis 1-10, since Genesis 1-10 likewise uses geographical names, personal names, and vocabulary which either didn’t exist at earlier times or had changed their meaning over time.

To take an example, the word “raqia” (firmament), is only found in Genesis 1, Psalm 19, Psalm 150, Ezekiel, and Daniel. In other words, outside Genesis 1, it is only found in exilic or post-exilic works. Earlier books of the Bible used a verb form of this word, but the noun form does not appear until the exilic era. We know that pre-exilic Hebrews had the concept of the firmament, but they didn’t use the word raqia to describe it, they used different words. It is only in the exilic era that raqia appears as a single word for the firmament. In pre-exilic books the word šāmayim is used for the heavens. In exilic books we find both šāmayim and raqia are used for the heavens.

Similarly, the Hebrew phrase for “breath of life” used in Genesis 2:7; 6:17; 7:15, 22, is not found anywhere else in Scripture. Elsewhere in the Bible, a completely different phrase was used consistently. However, this “breath of life” is found in the Eridu Genesis, a Sumerian text which was copied and read by the Babylonians, and would have been taught to Babylonian educated members of the Hebrew exilic elite (Daniel 1:3-4).

Wait a minute, you just removed the entire Deuteronomistic history. Why?

Arguably? Deuteronomy says explicitly that the purpose of the sabbath is to commemorate the exodus from Egypt, not the creation week. If the sabbath was instituted to commemorate the creation week, why didn’t Moses know about it?

The purpose of those points is to establish a terminus ad quo. Certain parts of Genesis 1-11 could not have been written earlier than the monarchy. That pushes the date forward. Then you look at other passages of Genesis 1-11, and you find that they indicate an even later date. You keep doing this until you find the terminus ad quo.

But that isn’t my argument. It isn’t just that the names aren’t mentioned (though since Genesis 12 to the end of 2 Kings contains many genealogical lists you have to explain why none of them go back any earlier than Abraham’s family), it’s the fact that the events and locations aren’t mentioned either; Eden, the serpent, the fall, the flood, the tower of Babel, all immensely significant and formative events, none of which are mentioned from Genesis 12 to the end of 2 Kings.

Well let me quote from someone who helpfully made a useful point about this.

The fact is that Genesis 1-11 contains strong literary parallels with a number of Akkadian and Sumerian texts, parallels which are not the product of oral tradition but which have the exactitude of literary tradition; a scribe was reading those texts and had them in mind when writing Genesis 1-11. This requires a scribe literate in Akkadian cuneiform, and the earliest indication we have that any Hebrew scribe was literate in Akkadian cuneiform, is in the exilic era.

I’ll begin with the Israelite knowledge of Akkadian cuneiform, and that this could only have been known during the exile and later periods. To help argue this, you quote no one else but myself when I argued that there was simply no knowledge of Sumerian/Akkadian/Babylonian knowledge to transfer to any biblical work. Two points must be made here. Firstly, I was applying this to Israel’s entire history, including during and after the exile. After the exile, there’s still not a single word in the entire Hebrew Bible directly derived from Sumerian, Akkadian, Babylonian, or other cuneiform languages. There still isn’t a single cuneiform inscription in the entirety of Israel during and after the exile. Secondly, I extensively explained how these near eastern myths, from Eridu Genesis to the Epic of Atrahasis ended up being embedded into the text of Genesis 1-11. This is what I said earlier:

What I’m suggesting is that these stories of the man and women in the garden with the tree, the confusion of the languages, the floods, etc, were common near eastern stories and motifs common to all ancient near eastern societies and cultures. These weren’t Sumerian stories or Egyptian stories, they were near eastern stories that would have been inherited from generation to generation by anyone living in the general near eastern area. In other words, these stories would have been with the Israelite people from the very beginning of their emergence, and the fathers of the ‘founders’ of Israel would have known them, and the fathers of the fathers of Israel’s founders would have known them, and the fathers of the fathers of the fathers of Israel’s founders would have known them, etc. Everyone would have known them, just like everyone in Europe knows about the story of Adam and Eve – it’s not that the British got the story from the Germans who got the story from the Greeks, it’s simply that the story of Adam and Eve is part of the common cultural milieu of European and western society, so it’s no surprise that the Brits know it, and the Brits knowing it doesn’t at all imply that they took it from one particular culture, nor does Israel knowing of the flood story imply that they in turn took the flood story from one particular culture (like Sumer). The flood story (and other stories) were not cultural stories, they were multi-cultural stories.

In my view, the Israelite’s did not get a working knowledge of these stories through reading the cuneiform tablets, these stories were common near eastern stories known to everyone in Israel at the time as they had been passed down from generation to generation throughout the ancient near east. You’ll realize that through the entirety of Genesis 1-11, the primeval history never directly quotes from any of these stories, it takes and transforms their framework and larger narrative into its own. They knew these stories, not by reading them, but because these stories were embedded into the cultural milieu of the ancient near east.

To take an example, the word “raqia” (firmament), is only found in Genesis 1, Psalm 19, Psalm 150, Ezekiel, and Daniel. In other words, outside Genesis 1, it is only found in exilic or post-exilic works. Earlier books of the Bible used a verb form of this word, but the noun form does not appear until the exilic era.

You’re going to need to be a little more specific than that. What was this ‘different form’ that is only used before the exile, and then evolves into the ‘noun form’ of raqia only during and after the exile? I went through Strong’s concordance, and could not find a single one. I already understand that the Hebrew language changed over time, however you still have not been able to demonstrate that these words didnd’t exist at earlier periods or only originated in these later periods. This is not at all analagous to using the words ‘radio’ or ‘television’ 300 years ago, these terms are very clearly documented and directly pertain to the invention of new technologies/things. There is no such invention in Genesis 1-11 that happened in the exilic/post-exilic eras.

Arguably? Deuteronomy says explicitly that the purpose of the sabbath is to commemorate the exodus from Egypt, not the creation week. If the sabbath was instituted to commemorate the creation week, why didn’t Moses know about it?

“Why didn’t Moses know about it?” seems like a strange question, tugging tightly on an argument from silence. Deuteronomy says the entire law originated as something Israel owed God after he brought them out from the land of Egypt. However, the sabbath day system of working for six days and resting on the seventh unequivocaly originates from the Israelite belief that God had worked six days in creating the heavens and the earth and then rested on the seventh. This is explicitly told to us in Exodus.

Exodus 11:8-11: Remember the sabbath day, and keep it holy. 9 Six days you shall labor and do all your work. 10 But the seventh day is a sabbath to the Lord your God; you shall not do any work—you, your son or your daughter, your male or female slave, your livestock, or the alien resident in your towns. 11 For in six days the Lord made heaven and earth, the sea, and all that is in them, but rested the seventh day; therefore the Lord blessed the sabbath day and consecrated it.

The Sabbath system derives from the creation week, and the Deuteronomistic history cites the sabbath system. And, according to what you first said on this thread;

If you want a more nuanced view, I regard most of the Pentateuch as pre-exilic, but Genesis 1-10 as exilic at earliest. See here4 for my reasons.

So, is Exodus 11 part of this “most of the Pentateuch” that you consider as pre-exilic? Because, if it is, this is an explicit pre-exilic citation of Genesis 1-11 that you’re looking for and should settle this. I definitely consider the entirety of Exodus to be pre-exilic, considering I think there’s significant evidence that Exodus utilizes pre-exilic, and sometimes very pre-exilic information and tradition.

I think, in conclusion, that your seven points can’t demonstrate an exilic/post-exilic composition of Genesis 1-11. Remember, two of your points only argue for a dating of after 1000 BC and 930 BC respectively, so you only really have five arguments that challenge my position that it was written anywhere from the 10th-6th centuries BC. I don’t think you’ve really proven any elements in Genesis 1-11 are exilic/post-exilic.

Apart from Ugarit? Why didn’t you mention Ugarit? Regardless, there is no need to identify words in the Hebrew Bible “directly derived from” other cuneiform languages (even though they are there). We have concepts, literary forms, and vocabulary in Genesis 1-11 which are clearly Sumerian and Akkadian imports. Genesis 1 itself starts with exactly the same literary form as the Eridu Genesis. I’ve already mentioned the “breath of life” import from Sumerian.

Ok so please present all the evidence that the Hebrews knew these stories, and that they were all well known to everyone in Israel, passed down from generation to generation. Are you going to argue that this was through oral tradition or something? Where is the evidence for this?

No it doesn’t quote them, it does something else; it polemicizes them, and it also follows their literary forms. It follows their literary forms so closely that it’s clear there’s a literary relationship between the texts. This is not a relationship which is sustained by oral tradition.

It’s easy to identify the difference. For example, at Megiddo a fragment of the Epic of Gilgamesh was found. It was a pedagogical text, a scribal writing exercise for students learning to be scribes. But it was not copied from a text of the Epic of Gilgamesh. It was written from memory, and the corruption and errors in the text indicates the scribe neither understood fully the language in which he was writing, or the text he was transcribing. This would not have happened if these stories were already a common part of Hebrew consciousness; a scribe who already knew the story would not be making such blunders, they would be so familiar with the story and its vocabulary that they would have written it accurately.

So why is it that Genesis 1-11 follows so closely even the literary forms of the Mesopotamian texts?

I already told you, it’s the verb form of raqia (the verb form is rāqaʿ). You can find it in texts such as Exodus 39:3, Numbers 16:39, 2 Samuel 22:43, and Job 37:18. It’s right there in Strong’s (#7554).

In case you haven’t realized, the burden of evidence is on you to prove that they did exist. I’ve already demonstrated that the pattern of distribution we have is exactly what we find with words which originate at a later date, words which even you acknowledge could not be early.

Of course there is, I’ve even shown you examples like the breath of life and raqia.

It is not an argument from silence; I pointed out that when Moses told Israel the reason for the sabbath, he said explicitly that it was a commemoration of the exodus. That’s not an argument from silence, that’s an argument from positive evidence. The burden is on you to explain why Moses said this, and didn’t say that the sabbath commemorates the seven day creation week.

Yes, but not all of it. Mainstream scholarship recognizes this reference to the creation week as a later addition, which was added only after Genesis was already written. It was not original to the pre-exilic text of Exodus 11.

On the contrary, the point is that if you acknowledge the evidence from points 1 and 2, then how can you deny the evidence of the other five points? On what basis do you acknowledge the linguistic argument in points 1 and 2, and then deny the same linguistic argument when it’s used later? Could I ask if you’ve looked at how much of the Hebrew in Genesis 1-11 is early, archaic, or late?

I am puzzled. @Jonathan_Burke has been explaining the evidence for why he thinks some texts are Exilic or Post-Exilic.

Then you argue that his evidence isn’t credible, since the only time Jewish scribes would know words as he suggests is in or after the Exile.

Well… yeah. That’s the point of the evidence!

When you write:

"I’ll begin with the Israelite knowledge of Akkadian cuneiform, and that this could only have been known during the exile and later periods. "

I’m looking around to see if anyone reading your statement is seeing the same thing I’m seeing. Yes. Right. Israelite knowledge could only have come from the Exile and Later Periods.

I think you are struggling with the idea that there is no law requiring several books in a historical timeline to be written in the same sequence!

In the Greek writings after Homer, several Greek writers expanded on a single sentence of Homer, and expanded the sentence into an entire “back story” - - to explain why Homer wrote the sentence he did.

In many cases, different Greek writers wrote different back stories - - because both writers had their own idea for what happened - - not because one or the other had special information on what actually did happen.

I think you would get more enthusiastic cooperation from @Jonathan_Burke if when you asked him to do you a favor you made some effort to have shown that you have read his material.

You ask “What is the reason for claiming this reference to the ‘creation week’ is a later addition…?”

Did you actually read this concluding paragraph from one of his posts?

“None of the books from Genesis 12 to the end of 2 Kings show any knowledge of Adam, Eve, the garden, the serpent, the fall, Cain and Abel, the flood, or the tower of Babel, the sabbath memorializing the creation (Moses explicitly says the sabbath memorializes the exodus from Egypt), or any of the events of Genesis 1-10. It’s not merely that these chapters aren’t quoted, it’s that most of the Old Testament shows no knowledge of them at all.”

Or perhaps you just forgot the point it was making.

If in Exodus Moses specifically states: “the sabbath memorializes the Exodus from Egypt…”, and if Moses had also written the story of the Creation Week (the other reason for the Sabbath?), don’t you think he would have mentioned it instead, or along with, his other statement?

On the other hand, if someone was writing a long set of telescoping backstories for Exodus (aka, Genesis), it would be understandable that the writer does not allude to Exodus, because that would prove Genesis was written after Exodus, and the scribe didn’t want to interfere with the “focus” on the first days of creation.