Well, I warned you that the topic is a relatively new area of research. Without knowing what you’ve googled, I can say that just about anything prior to 2018 may mention the fact of globularity but won’t be much help explaining its implications for the evolution of the brain/mind. I already pointed you to a couple of the key studies, but I’ll take one more crack at it and see if I can make it clearer.

The following illustration is from Neandertal Introgression Sheds Light on Modern Human Endocranial Globularity (2019)

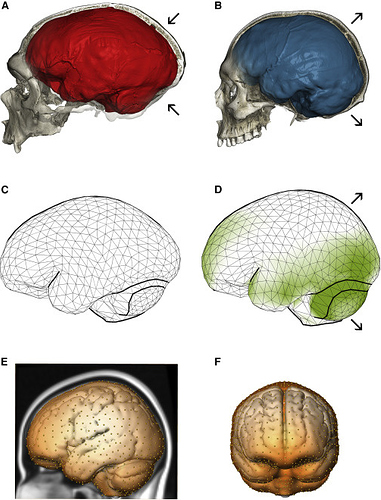

Figure 1. Endocranial Shape Differences between Neandertals and Modern Humans

(A) CT scan of the Neandertal fossil from La Chapelle-aux-Saints with a typical elongated endocranial imprint (red).

(B) CT scan of a modern human showing the characteristic globular endocranial shape (blue). Arrows highlight the enlarged posterior cranial fossa (housing the cerebellum) as well as bulging of parietal bones in modern humans compared to Neandertals.

(C ) Average endocranial shape of adult Neandertals; each vertex of the surface corresponds to a semilandmark.

(D) Average endocranial shape of modern humans. Areas shaded in green are relatively larger in modern humans than in Neandertals.

The areas shaded in green are the areas of interest, primarily the parietal lobes and cerebellum. In the article on The evolution of modern human brain shape (Jan 2018) the authors explain:

Two features of this process stand out: parietal and cerebellar bulging. Parietal areas are involved in orientation, attention, perception of stimuli, sensorimotor transformations underlying planning, visuospatial integration, imagery, self-awareness, working and long-term memory, numerical processing, and tool use ( 44 – 49 ). … The cerebellum is associated not only with motor-related functions like the coordination of movements and balance but also with spatial processing, working memory, language, social cognition, and affective processing ( 52 – 55 ).

The changes in the sapiens brain related to globularity provided advantages in key areas: mainly planning, working memory, tool use, sociality, and language. When these suites of capacities were gradually added to the toolbox of the mind from 100,000-35,000 years ago, the results were dramatic.

It is intriguing that the evolutionary brain globularization in H. sapiens parallels the emergence of behavioral modernity documented by the archeological record. First, the emergence of the Middle Stone Age is close in time to the currently earliest known fossils of early H. sapiens ( 17 ) that had large brains but did not exhibit any major changes to (outer) brain morphology ( 20 ). Second, as the H. sapiens brain gradually became more globular, features of behavioral modernity accumulated gradually with time ( 27 ). Third, at the time when brain globularity of our ancestors fell within the range of variation of present-day humans, the full set of features of behavioral modernity had accumulated at the transition from the Middle to the Later Stone Age in Africa and from the Middle to the Upper Paleolithic in Europe around 50,000 to 40,000 years ago ( 26 ). In this context, the “human revolution” just marks the point in time when gradual changes reach full modern behavior and morphology and does not represent a rapid evolutionary event related to only one important genetic change that leads to a rapid emergence of modern human brain morphology and behavioral modernity.

The article on Reconstructing the Neanderthal brain using computational anatomy (April 2018) reached similar conclusions. I already quoted from it in post #44 above, so I’ll just throw in another quick snippet:

There is now strong evidence that the cerebellar hemispheres are important for both motor-related function and higher cognition including language, working memory, social abilities and even thought32,33,34. Further, whole cerebellar size is correlated with cognitive abilities, especially in the verbal and working memory domain35. Thus, we examined the relationship between cerebellar volumes and various cognitive task performances using a large data set from the human connectome project (see Methods). Multiple regression analyses revealed that attention and inhibition task score was most strongly correlated with size-adjusted whole cerebellar volumes ( t 1090 = 4.27, p < 0.001), followed by cognitive flexibility task score ( t 1090 = 3.24, p = 0.001). There was also a significant correlation of size-adjusted cerebellar volumes with speech comprehension ( t 1090 = 3.33, p = 0.001), speech production ( t 1090 = 2.86, p = 0.004), working memory ( t 1090 = 2.92, p = 0.004), episodic memory ( t 1090 = 2.84, p = 0.005) task scores, but not with processing speed task score ( t 1090 = 1.29, p = 0.199). Note that the functions such as attention, inhibition, cognitive flexibility, working memory, are thought to be main components of executive functions36. These results indicate that the cerebellar hemispheres are involved in the abilities of executive functions, language processing, and episodic memory function.

The expansion of the cerebellum also relates to the book you asked @DOL about. Until recent neuroimaging advances showed otherwise, the cerebellum previously was thought to contribute primarily to the planning and execution of movements. But a 2012 article on Embodied cognitive evolution and the cerebellum presents “a synthesis of the comparative, anatomical and functional neuroscience data” that “stresses the unity of sensory–motor and cognitive evolution.”

Classically, distinctions are made between cognition, as a process of interpreting and integrating information about the outside world, the perceptual information that this process is about, and the motor commands that represent the output of cognitive processes [27]. More recently, these distinctions have been broken down by the recognition that cognition is best conceived as a set of processes mediating the adaptive control of bodies in environments: the concept of embodied cognition [28–33]. This perspective suggests that ‘a key aspect of human cognition is … the adaptation of sensory-motor brain mechanisms to serve new roles in reason and language, while retaining their original function as well.’ [34, p. 456].

In short, a more spherical braincase reflects changes to the underlying architecture of the brain, which resulted in a modern sapiens brain that is capable of thinking much differently than previous hominins, including Neanderthal.