while it’s true that the Greek word plērōma (translated “fullness”) carried philosophical weight in certain Hellenistic circles, especially among Gnostics and Platonists, its use in Colossians 2:9 is firmly rooted in Paul’s theological declaration, not in borrowed pagan philosophy. Paul was not trying to introduce a philosophical nuance but rather to make an unambiguous, Spirit-inspired statement: “For in Him dwelleth all the fullness of the Godhead bodily.” That word plērōma here simply and powerfully means the entirety, completeness, and total expression of the Divine Nature—not a portion, not an emanation, but all that God is—dwelling permanently in the person of Jesus Christ in bodily form. Paul is not appealing to Greek philosophy; he is directly confronting it. Gnostics said divinity couldn’t dwell in matter—Paul says God did. And not partially, but fully. So the “hint” isn’t in philosophy—it’s in revelation. Jesus isn’t a reflection of deity or a conduit of divine light—He is God Himself in revealed flesh.

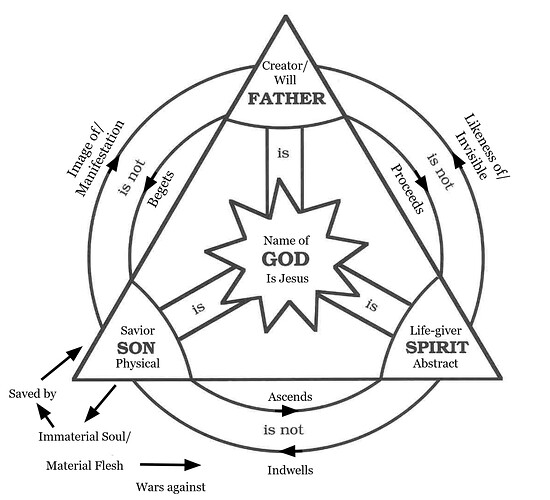

I hear your concern, but I assure you, my understanding of the Trinity doctrine is not based on caricature or ignorance—it’s based on years of study, prayer, and careful comparison of creedal theology with the full witness of Scripture. The traditional doctrine of the Trinity, as defined by councils and creeds, posits that within the one divine essence there are three distinct persons ( internal division)—Father, Son, and Holy Spirit—each fully God, co-equal, co-eternal, yet not each other. That framework introduces three centers of self-awareness within the one divine Being, even if proponents insist these “persons” are not separate beings. What I am presenting is not a misunderstanding of the Trinity but a deliberate rejection of its internal division in favor of biblical, apostolic Oneness—that God is indivisibly One, not merely in essence, but in identity. Deuteronomy 6:4 declares, “Hear, O Israel: The LORD our God is one LORD,” and the New Testament affirms that this one God was manifest in the flesh as Jesus Christ (1 Timothy 3:16). I do not deny the Father, Son, or Holy Ghost—I understand them not as three persons, but as manifestations or roles of the one true God, revealed in different ways across time (simultaneously not sequentially like Modalism) and fully in the man Christ Jesus. This is not confusion—it is the glorious mystery of godliness, revealed to those who seek Him in Spirit and in truth.

With respect, appealing to New Testament Greek grammar as the sole foundation for the doctrine of the Trinity oversimplifies the issue and misunderstands the role of language in theology. Grammar can show distinction between speakers or roles, but it cannot, on its own, establish ontological divisions within the Godhead. Just because the Father speaks to the Son, or the Son prays to the Father, does not necessitate separate divine persons any more than David speaking to his own soul (Psalm 42:5) means he is multiple beings. The language of Scripture accommodates the incarnation—God manifest in flesh (1 Timothy 3:16)—and reveals a real distinction between deity and humanity in the person of Jesus Christ. The Son is not a pre-existent person alongside the Father, but the man through whom the invisible God chose to reveal Himself (John 1:18; Colossians 1:15). Greek grammar affirms the reality of the incarnation, not an eternal plurality within God. The true foundation is not grammatical distinction, but divine revelation: “Hear, O Israel: The LORD our God is one LORD” (Deuteronomy 6:4), and Jesus is the visible image of that one invisible God—not a second divine person, but God with us (Matthew 1:23).

These Scriptures below show no face to face intimacy in eternity past.

- Isaiah 44:6: “Thus saith the LORD the King of Israel, and his redeemer the LORD of hosts; I am the first, and I am the last; and beside me there is no God.”

- Isaiah 44:8: “Fear ye not, neither be afraid: have not I told thee from that time, and have declared it? ye are even my witnesses. Is there a God beside me? yea, there is no God; I know not any.”

- Isaiah 45:5: “I am the LORD, and there is none else, there is no God beside me: I girded thee, though thou hast not known me:”

- Isaiah 45:21: “Tell ye, and bring them near; yea, let them take counsel together: who hath declared this from ancient time? who hath told it from that time? have not I the LORD? and there is no God else beside me; a just God and a Saviour; there is none beside me.”

- Isaiah 46:9: “Remember the former things of old: for I am God, and there is none else; I am God, and there is none like me,”

- Deuteronomy 32:39: “See now that I, even I, am he, and there is no god with me: I kill, and I make alive; I wound, and I heal: neither is there any that can deliver out of my hand.”

- Isaiah 43:11: “I, even I, am the LORD; and beside me there is no saviour.”

- Hosea 13:4: “Yet I am the LORD thy God from the land of Egypt, and thou shalt know no god but me: for there is no saviour beside me.”

It’s not adding to the text—it’s rightly interpreting it in light of the whole counsel of Scripture and the Hebrew understanding of monotheism. Deuteronomy 6:4 declares, “Hear, O Israel: The LORD our God is one LORD.” The Hebrew word for “one” (echad) in this context doesn’t imply a compound unity, but a singular, indivisible essence. This is not an imposition on the text but a faithful rendering of what Moses and the Hebrew people understood about God—that He is not divided in personhood or being.

To say that the Father is not the Son and the Son is not the Spirit, yet each is fully and distinctly God, is to introduce a structure within the divine identity that Scripture itself never reveals. That’s not clarity—it’s theological layering born from post-biblical development. Oneness theology doesn’t add to the text; rather, it guards the simplicity and purity of biblical monotheism by affirming that God has revealed Himself as one undivided person—manifesting Himself as Father in creation, Son in redemption, and Holy Ghost in regeneration. The Incarnation was not the arrival of a second divine person but the self-revelation of the one true God in visible form (John 1:14; Colossians 2:9; 1 Timothy 3:16). This is not an addition to Scripture—it’s a return to it.