- Who says heretics don’t cry?

The Bible does not use the phrase “God the Son” even one time. It is not a correct term because the Son of God refers to the humanity of Jesus Christ. The Bible defines the Son of God as the child born of Mary, not as the eternal Spirit of God (Luke 1:35). “Son of God” may refer to the human nature or it may refer to God manifested in flesh—that is, deity in the human nature. “Son of God” never means the incorporeal Spirit alone, however. We can never use “Son” correctly apart from the humanity of Jesus Christ. The terms “Son of God,” “Son of man,” and “Son” are appropriate and biblical. However, the term “God the Son” is inappropriate because it equates the Son with deity alone, and therefore it is unscriptural. The death of Jesus is a particularly good example. His divine Spirit did not die, but His human body did. We cannot say that God died, so we cannot say “God the Son” died. On the other hand, we can say that the Son of God died because “Son” refers to humanity.

If we could justify the use of the phrase “God the Son” at all, it would be by pointing out, as we have done, that “Son of God” encompasses not only the humanity of Jesus but also the deity as resident in the humanity. However, John 1:18 uses “Son” to refer to the humanity, for it says the Father (the deity of Jesus) is revealed through the Son. This verse of Scripture does not mean that God is revealed by God but that God is revealed in flesh through the humanity of the Son. "Son of God” refers to the humanity of Jesus. Clearly the humanity of Jesus is not eternal but was born in Bethlehem. One can speak of eternal existence in past, present, and future only with respect to God. Since “Son of God” refers to humanity or to deity as manifest in humanity, the idea of an eternal Son is incomprehensible. The Son (God’s Humanity) of God had a beginning.

St. Roymond, I hear where you’re coming from, but I believe the issue lies in assuming that everything God expresses must be categorized as a separate “Person” in order to preserve unity. From my perspective, it’s actually the opposite—dividing God into separate “Persons” introduces internal complexity and division that Scripture never demands. When I say the Word (Logos) is not a second Person, I’m not suggesting that the Word is some impersonal fragment of God. I’m saying the Word is God Himself in self-expression—His mind, will, intent, and power expressed outwardly, not a distinct being alongside Him.

God is a perfect unity—not a unity of persons, but a unity of being. The Logos is not “less” than God because it’s not a second person—it is God, fully and completely. When John says “the Word was with God and the Word was God,” he’s not introducing plurality within God, but rather revealing the dynamic self-revelation of the invisible Spirit. And when the Word became flesh, that self-expression was made visible in the man Christ Jesus.

I believe God’s unity is preserved not by inserting multiple Persons into the Godhead, but by understanding the Word as God’s own divine utterance—inseparable from Him, yet revealed in time through the incarnation. This view keeps God undivided, consistent with Isaiah 44:24, where He declares He created all things alone. For me, that’s not a limitation—it’s the beauty of divine simplicity and the mystery of the Incarnation all in one.

Thanks, St. Roymond—I see where you’re coming from, but I have to respectfully disagree. While the Greek term πρωτότοκος (prototokos) can carry philosophical connotations, I don’t believe Paul was writing Colossians 1:15–18 with Greek metaphysics in mind. He was a Jewish thinker rooted in the Hebrew Scriptures, and when I look at how firstborn is used biblically, especially in Old Testament contexts, it’s clear that it often refers to rank or preeminence, not biological origin or eternal preexistence. For instance, in Psalm 89:27, God says of David, “I will make him my firstborn, higher than the kings of the earth.” But David wasn’t literally born first—he was the youngest of Jesse’s sons. The title was one of status and election.

That’s why I said “firstborn over all creation” speaks of Christ’s supremacy and purpose, not His origin. The very next verses in Colossians 1 clarify this: “By Him were all things created… all things were created by Him and for Him.” That’s not a philosophical treatise—it’s Paul declaring that Christ, as the visible image of the invisible God, is supreme over creation because all things were created through Him and for Him. He is the agent of creation as the Eternal Word (which spoke the world into being) not pre-existent Son.

So when I read “firstborn of all creation,” I don’t hear Plato—I hear the Holy Spirit proclaiming that Jesus is preeminent in purpose and authority, not a being who existed prior in some mystical chain of emanations, but as the full manifestation of the invisible God in time. That’s what matters most to me—not speculative metaphysics, but the revealed truth of who Jesus is as the fullness of God bodily.

I appreciate the engagement, and I understand why someone might highlight the Greek phrase πρὸς τὸν Θεόν in John 1:1 to suggest a face-to-face relationship between two distinct entities. But I see that differently—because we must interpret Greek grammar through the lens of revealed theology, not impose post-biblical categories on a verse that isn’t teaching what later creeds assume.

When I read πρὸς τὸν Θεόν, I don’t immediately think of two divine persons standing across from each other. Instead, I understand it as the Word being in intimate, direct communion with God—His own self-expression, His own Logos. That phrase doesn’t force me to picture two “Gods in dialogue” or distinct beings, but rather points to the dynamic relationality within God’s own being. The Word isn’t a second self, but God’s uttered thought, His internal wisdom turned outward, which becomes flesh in the person of Jesus Christ.

Colossians 1 calls Jesus the “image of the invisible God.” That doesn’t mean He is beside the invisible One—it means He is the visible manifestation of the One who cannot be seen. The Word was always “with” God in the sense that God’s self-expression has never been separate from Him. When the Word becomes flesh (John 1:14), we are not seeing a second divine being step forward—we’re seeing the only God now revealed in bodily form (Colossians 2:9). That’s how I see the beauty of Oneness—God didn’t send someone else. He came Himself.

Brother St. Raymond, I hear where you’re coming from, but let me share where I’m coming from—because for me, this isn’t just a matter of terminology. It’s about staying faithful to the way Scripture reveals the identity of Jesus. When I say that it wasn’t “another divine person” who came to redeem us, but God Himself, I’m echoing the truth that the Word was God—not a separate person from God, but God’s own self-expression (John 1:1).

Now, here’s what I’d like you to consider: does your spoken word have a body? When you speak, your word proceeds from you—it’s you expressing your will, your nature, your intent—but it doesn’t walk around in bodily form. So why would we assume that God’s Word, before the incarnation, had a separate bodily personhood or distinct identity apart from God Himself?

The Word did not have a body until the fullness of time (Galatians 4:4), when it was made flesh (John 1:14). That’s not a second divine person becoming human—it’s the one true God stepping into His own creation in a visible, tangible way through the man Christ Jesus. The Word was always with God in the sense that it was in God—inseparable from His being, as a man’s word is inseparable from himself. But the Word became a Son when it took on flesh. That’s when the visible expression of the invisible Spirit began (Colossians 1:15; 1 Timothy 3:16).

So this isn’t about semantics—it’s about affirming the oneness of God and the beauty that our Redeemer is not someone sent by God in the way a subordinate goes on an errand, but God Himself, manifest in the flesh.

I do. I say heretics cry—because I’ve seen it. I’ve felt the weight of deception lift off someone when the truth of who Jesus really is breaks through centuries of confusion. I’ve watched people weep when they realize that it wasn’t a second person or a co-equal being that died for them—it was God Himself, robed in flesh, reaching all the way down to save us. That kind of revelation shatters pride, breaks chains, and yes—it brings tears.

So if someone wants to call me a heretic for believing that the fullness of the Godhead dwells bodily in Jesus (Colossians 2:9), for proclaiming that the Sonship had a beginning in time, and that Jesus is not one person in the Godhead but rather the one true God manifested—then I’ll gladly cry too. Not out of shame, but out of gratitude that the mystery has been revealed, and the veil torn. Because I’d rather be called a weeping heretic in the eyes of man than a dry theologian who never touched the hem of His garment.

Ah! This sounds more like the Oneness Pentecostal view of Jesus, which is basically a form of modalism.

We are all heretics to some group or another. So it is not a meaningful distinction really. But in all honesty we can say it doesn’t fit the earliest definitions of “Christianity.” But that is just a human word with a human definition.

Though to be frank, a lot of these Christological controversies look a bit pompous to me – pretending we can really know such things about God.

Nevertheless, I like the Trinitarian view. It is not really in the Bible (at most logically derived from the Bible), and it is pretty weird – nothing like us at all. But that is exactly what I like about it. This is not a God made in our own image. Personal God? Yes. Even a trans-personal God. One being, more than we are and not less than we are in any way. This is an infinite God not bound by our limitations. Three in one? NO! But the Father, Jesus, and Holy Spirit as three distinct persons while being one God? Yes. Not modalism.

Is modalism bad? I would say it is the Hindu way of thinking. And frankly also how a great many Christians understand the Trinity. But no, I don’t see anything bad about it. …unless… this is made into some kind of criteria for salvation. Then not only is that legalistic Gnosticism but is far too much like betting your salvation on the correctness of your own understanding.

Oh… and got to remind people that we need to connect this discussion up to the relationship between science and religion… OK. How about contrasting such theological details with the details in science. In science we have objective measurable ways of determining answers. But for things like this, is it really any more substantial than our preference for a favorite flavor of ice cream?

Mitchell, I appreciate your tone of civility and your openness to engage the deeper matters of faith. But with all due respect, to suggest that these Christological distinctions are no more substantial than preferences for “a favorite flavor of ice cream” misses the eternal weight and sacredness of what’s truly at stake. This isn’t academic speculation—it’s about the identity of the One who bled and died for our redemption. The earliest definitions of Christianity weren’t shaped by post-apostolic councils or evolving philosophical constructs, but by the witness of the apostles who declared with certainty that “God was manifest in the flesh” (1 Timothy 3:16), and that “in Him dwelleth all the fulness of the Godhead bodily” (Colossians 2:9).

It’s not pompous to confess what God has revealed—it’s humble obedience to the mystery now made manifest (Romans 16:25–26). Trinitarianism, as you rightly admit, is a logical framework not explicitly found in Scripture. But my faith doesn’t rest on logic alone—it rests on revelation. The Oneness of God is not a philosophical box, nor is it “modalism” as a caricature. It is the unveiled truth that the invisible, eternal Spirit took on flesh—not to send someone else, but to come Himself (Isaiah 43:11; John 14:9–10). That’s not legalism. That’s love. That’s the gospel.

The danger isn’t in caring too much about theology—it’s in caring too little. The apostles didn’t die for ice cream preferences. They were martyred for the name of Jesus because they knew who He was. And when that same revelation breaks through today, it still makes heretics cry. Not because they’re wrong, but because the veil has been lifted, and they’ve seen the One who sits on the throne—and His name is Jesus.

Mitchell, I appreciate your engagement, but respectfully, what you’re labeling as “modalism” misrepresents what Oneness believers actually affirm. Modalism, historically, teaches that God is one person who merely switches roles or “modes” over time—first as Father, then as Son, then as Spirit—like an actor changing masks. That’s not what we believe. The Oneness view holds that the one true God—the eternal, omnipresent Spirit—manifested Himself in flesh as Jesus Christ (1 Timothy 3:16). This isn’t a shift in mode but a powerful incarnation: the invisible became visible, the eternal stepped into time, not as a new person in a triune Godhead, but as the fullness of the Godhead bodily (Colossians 2:9).

Jesus prayed, suffered, and died—not as a mere mask or role, but as a fully human man, while the eternal Spirit of God remained omnipresent and active. This is not a denial of Christ’s dual nature—it’s a defense of it. We proclaim with awe and tears that the man Christ Jesus is the express image of the invisible God, not a second divine person, but God Himself come down in redemptive mercy. So when the revelation hits that it wasn’t one-third of a divine committee who went to the cross, but the God who said, “I am the Lord, and beside Me there is no savior”, it breaks hearts and opens eyes. That’s not modalism—it’s the mystery of godliness.

Modalism is short for modalistic monarchianism and is defined as a theological concept which denies the distinct persons of the Trinity (Father, Son, and Holy Spirit).

Modalistic Monarchianism is accepted within Oneness Pentecostalism. (Wikipedia)

Let us be clear. This is Isaiah 43, and NOT something Jesus said in His ministry on earth.

To me it is just semantics.

Frankly I think getting excited and tearful about such a thing is very very very far from the heart of Christianity. A bit of a turn off, frankly. So… sorry… not interested.

Mitchell, the assertion that “Modalistic Monarchianism is accepted within Oneness Pentecostalism” is a common oversimplification that doesn’t do justice to what Oneness theology actually teaches. Despite what you may read on Wikipedia or in some theological summaries written from Trinitarian perspectives, Oneness believers do not adhere to the same kind of Modalism that was condemned in the early centuries of church history—especially the version attributed to Sabellius, which taught that God was one person who revealed Himself in successive, non-overlapping roles like Father, then Son, then Spirit.

Oneness Pentecostals do affirm that there is only one God, and that this one God revealed Himself as Father in creation, as the Son in redemption, and as the Holy Ghost in regeneration and empowerment. However, these are not merely “modes” or “masks” that God puts on and off. This is not a case of God pretending to be different persons at different times. Instead, Oneness theology holds that the one eternal, invisible God chose to reveal Himself fully and permanently in the man Christ Jesus—not as a temporary role, but as the literal incarnation of His divine identity (John 1:1, 14; Colossians 2:9).

What sets this apart from ancient Modalism is that Oneness doctrine preserves the distinction between the humanity of Christ and the eternal Spirit who indwelt Him. When Jesus prayed, submitted, and spoke of “the Father,” He was not speaking as a divine person to another divine person, but rather from His fully human consciousness relating to the divine nature that filled Him (John 14:10). That’s not Modalism—it’s the mystery of godliness: God was manifest in the flesh (1 Timothy 3:16).

The word “manifest” is critical here. It means to make visible what is otherwise invisible. Oneness theology teaches that Jesus is the visible manifestation of the invisible God, not a second divine person alongside the Father, but the Father revealed (John 14:9). The Holy Ghost, likewise, is not a separate being, but the same Spirit of the Father working among and within believers. So, the distinctions Oneness Pentecostals make are functional and relational, not personal and co-eternal in the way Trinitarianism demands.

Furthermore, the label “Modalistic Monarchianism” is typically used by critics to dismiss Oneness theology without seriously engaging its scriptural basis. It’s a theological shortcut that avoids having to wrestle with the Oneness position’s use of Isaiah 9:6, John 10:30, John 14:9, Colossians 2:9, and Acts 2:38, among many others, which affirm that all the fullness of the Godhead is revealed in Jesus Christ. Unlike classical Modalism, which had little room for real human consciousness in Christ, Oneness theology robustly affirms both the humanity and divinity of Jesus in one person—God and man united without division.

So, while the term “Modalistic Monarchianism” might be convenient for classification, it is not a fair or accurate description of what Oneness Pentecostals believe. It’s important to listen to their theology on its own terms rather than framing it through historical categories that don’t quite fit. Oneness believers do not reduce God to a shape-shifting being moving through time in costume changes—they exalt the one eternal Spirit who has forever revealed Himself in Jesus Christ, and through Him, made known His saving name and nature.

Your response attempts to sidestep the theological weight of Isaiah 43:11 by reducing it to a historical context, suggesting it holds no relevance to Jesus simply because He didn’t cite it directly during His earthly ministry. But this line of reasoning is shallow and dismissive of how Scripture reveals truth—not just through quotation, but through fulfillment and manifestation. Isaiah 43:11 is more than just a prophetic statement; it is a divine claim: “I, even I, am the LORD; and beside Me there is no savior.” This is an absolute and exclusive declaration. God is not merely saying He is one savior among many. He is saying, there is no savior beside Me—no parallel, no co-equal, no second divine person.

Now fast-forward to the New Testament, where we’re told again and again that Jesus is our Savior. Luke 2:11 says, “For unto you is born this day in the city of David a Saviour, which is Christ the Lord.” Acts 4:12 boldly proclaims that “there is none other name under heaven given among men, whereby we must be saved.” And Titus 2:13 calls Him our “great God and Saviour Jesus Christ.” So, unless we’re ready to claim there are now two saviors—one in Isaiah and one in Jesus—we are left with only one conclusion: Jesus is the LORD of Isaiah 43:11.

This is not eisegesis or doctrinal overreach. This is rightly dividing the Word of truth. The New Testament writers understood that Jesus didn’t need to go around quoting every Old Testament verse for them to see He was the fulfillment of those very texts. In John 5:39, Jesus says, “Search the scriptures; for in them ye think ye have eternal life: and they are they which testify of Me.” The Scriptures bore witness of Him—sometimes explicitly, sometimes typologically, sometimes prophetically—but always truthfully.

The claim that “Jesus didn’t say it, so it doesn’t apply” is not only a weak argument—it undermines the very fabric of how Scripture testifies to the unity of the Godhead. The same LORD who declared in Isaiah that there is no savior beside Him is the very one who walked among us, wrapped in flesh, and gave Himself for the salvation of the world. He didn’t have to say Isaiah 43:11—He proved it with nail-scarred hands and a resurrected body.

Mitchell, I understand that to some, distinctions between “God the Son” and “God Himself in Christ” may seem like mere semantics. But in truth, these distinctions have real theological and emotional consequence. They’re not about hair-splitting—they’re about the very substance of divine love and how we understand who went to Calvary.

When I say that it brings me to tears to realize God Himself died for me—not a delegate, not a proxy—it’s not hyper-emotion; it’s a reaction to a spiritual and cosmic truth that echoes through the very fabric of reality. This is no distant deity outsourcing redemption. This is the Creator stepping into His own creation to bleed for it.

And here’s where science helps us reflect: physics tells us that space and time themselves are part of the fabric of the created universe. That means the Eternal entered into space-time, clothed Himself in the fragile form of a human body—flesh made of atoms, powered by mitochondrial energy, strung together by DNA—and subjected Himself to the very laws He authored. That is not abstract. That is staggering. The omnipresent Spirit, unbounded by dimension, focused Himself into one human vessel (Colossians 2:9), not just to observe suffering, but to experience it fully—cell by cell, nerve by nerve, heartbeat by heartbeat.

Neurology teaches us the intensity of human pain and the complexity of emotional anguish. Jesus didn’t skip over that. He felt the thorns, He felt the betrayal, and He felt the forsakenness. And this wasn’t a divine actor putting on a show—it was the Almighty experiencing our frame from the inside out. Hebrews 2:14 tells us He “partook of flesh and blood,” not to perform, but to redeem. He didn’t just simulate death—He tasted it, so He could destroy it.

That’s why I say this is not a theological sideshow—it’s the core of redemption. When I realize the One who said “Let there be light” (Genesis 1:3) allowed that light to be snuffed out in a tomb—for me—it wrecks me in the best way. This is not emotional manipulation. It’s the only logical response to incarnate glory and sacrificial love.

To dismiss that as “semantics” is like saying Einstein’s equations and a child’s wonder at the stars are the same because they both talk about space. No—one might describe the mechanics, but the other captures the meaning. And Christianity is not just a religion of mechanism—it is a revelation of meaning. The cross isn’t just how sin was dealt with—it is how God showed us who He really is.

So no, I don’t apologize for being moved. I am undone by the revelation that the One true God didn’t send someone else. He came Himself. Not as part of Him, not as a fraction of a tri-personal being—but as the fullness of God bodily (Colossians 2:9). That’s not just the heart of Christianity—it’s the heartbeat of the universe.

I think there is a danger of taking human understanding and doctrine as sacrosanct or some sort of unalterable truth.

The Trinity is a human construct designed to encourage or help understanding. It is not God or even, necessarily God’s view of Himself.

Richard

I have heard a saying that if you can explain God (logically). then your god is so small that he fits into your head.

I assume and believe that God is above and beyond anything created. In our created reality, theological doctrines about who God is are just attempts to find words for something that may be beyond our comprehension.

Theology and science seem to differ fundamentally in the reliance on logical reasoning and testing of hypotheses.

Science relies on logical reasoning, math and testing (experimentation) – credible explanations need to be explained by the rules of this (created) universe and proven to be the best available description of what is known about the phenomenon.

When we are talking about God, logical reasoning based on the rules of this universe may not be enough, and it is difficult to think of an experiment that would show who God is. I do not want to underrate logical thinking, we need logical thinking when trying to understand matters related to God. I am just saying that logical thinking may not be enough because we do not always have sufficient information and we may not know if our basic assumptions are correct.

I could also claim that the biblical scriptures are not theology. What I mean with this claim is that these scriptures do not give a systematic presentation of basic doctrines. Creeds and attempts to define Trinity or the nature of Christ are strongly based on what is written in the recognized canonical scriptures (scriptures are what we have left of early apostolic teaching) but these doctrines are interpretations. We may compare interpretations and doctrines based on how well these seem to fit to the apostolic teaching, as described in the biblical scriptures. That may tell that one interpretation/doctrine seems to be more credible than the competing alternatives. Yet, when we are talking about God there is always a chunk of mystery involved.

It is fine and often necessary to compare differing interpretations and doctrines to see which one is the most credible alternative. When the subject is God, Trinity or the nature of Christ, it is good to remember that our explanations are just attempts to find words for a mystery – it is not wise to claim that we, and only we, know the (whole) truth.

Personally I believe he’s a created being. He’s the power of god placed inside of a child and that child was guided into being the messiah and given a name above all names, and authority equal to god.

![]()

Maybe what used to be considered a mystery is less so now?

Multitasking and things that have more than one function are common place. Three in one is simple when compared to the modern mobile phone.

Richard

Trinitarians believe and feel all the same things all through history and Jesus IS God Himself, just the same for them. The semantics is the big deal you are making of a theological detail. The turn off is your dismissal of the shared Christian experience to act like this is something experienced by only those who agree with this new doctrinal detail of your one little group. Frankly it just looks to me like a piece of manipulation to get people to accept all the other doctrine and practices you are pushing. Like I said: not interested, not going to happen.

Very good. I would point out the implication of this understanding the incarnation as becoming part of the space-time structure subject to the laws of nature is the resurrection transcending the laws of nature to become a spiritual body (1 Cor 15) means all the science (atoms and DNA) no longer applies. Jesus is no longer among us like a neighbor but belonging to the heavenly outside of the space-time of the physical universe.

YES!

Theology relies on logical reasoning, reading the scriptures, and to a small extent on practical considerations of how it plays out in church and history.

I would say, in agreement with Richard, same in both science and theology, that we simply be careful not to confuse the constructs we make to understand things with the things themselves. The theories of science isn’t nature any more than the theology is God.

Thanks for explaining yourself, Omega. I like the phrase “The human mind is a factory of idols.”

Quite so…and the topic at hand is likely to turn it into a warehouse— that is, with someone on a forklift zipping here and there between tall stacks of crates and cartons looking for the keg of beer that fits the customer’s request perfectly.

Before you disect “what the Scriptures exactly say about the Son,” it would be best to know what they exactly say, and then just stick with it. In Genesis 1:1, from what I have seen the phrase “God created” – emphasizes the plural character of the One Divine Being .,… In Genesis 18, Who were those three beings who visited Abraham and Sarah? There could be a whole conversation just on that…but that is not the subject here so much as a Three-in-One concept which seems to require that all three are Uncreated Beings. There ARE religions that have god or gods being born out of a seashell or lotus flower – or just re-heated from some previous incarnation. But this is not how the Hebrew scriptures—from which Christian tradition takes its beliefs – ever saw things. Early rabbis also wondered about “two powers in heaven” or similar. Rabbinic scholars such as Boyarin and Flusser have located the concept of a complicated Deity back into the first century BC/BCE—and link it to the visions of Daniel and some intertestamental writings. They indicate that rabbinic sources dropped the “complex deity” model once they saw what followers of Jesus did with it.

SAs Anselm of Canterbury put it “I do not seek to understand so that I may believe, but I believe so that I may understand.”

My supposition is that the perplexing scenes in Daniel —perhaps this would be questions about the identity of that “fourth man” in the flames with Daniel and friends --the one people at the time said “looked like a son of the gods” inspired the concept of some complex nature to God… as well as the later visions of Daniel 10 — the one where he sees “a man dressed in linen, his face like lightning, his eyes like flaming torches, his arms and legs like the gleam of burnished bronze, and his voice like the sound of a multitude”—yeah, I think a vision like that would rattle me a bit ( were it me) and the following visions of the future —would promote all sorts of speculation about the nature of this One God.

To repeat Anslem again—“…I believe so that I may understand”…

Or consult the

famous “Son of God Scroll” from Qumran:

Son of God he will be hailed, and Son of the Most High they will call him. Like the flashes {i.e. comets}

2 that you saw, thus their kingdom will be: (for) years they will reign over

3 the earth and will trample all. (One) people will trample on (another) people and (one) province on (another) province,

I know there are arguments as to who came up with the idea of a Trinity, but it seems to go back into the centuries before Christ, and got reworked in the late first century following His crucifixion and resurrection. Von harnack named Tertullian as the father of the Trinity idea, but Wrfield said Tertullian was simply passing on old thoughts long held.

SoIn that case, the concept of a Trinity and when did Jesus become Jesus (and the Son) are simply add-ons to what was already, before Christ came on the scene, a part of theological thinking. If God created humanity in His image, yet they were male and female—but both in His image —why can Jesus not “also” be God and the Spirit be God and the Father also be God? Jesus isn’t the Father , but it does not mean He is not Yahweh…and the Spirit is not Jesus --but He IS in a way --and it does not mean He is not also Yahweh.

"That is how Jesus could say “He who has seen Me has seen the Father” and “Before Abraham was, I am.”

“But when the fullness of time came, God sent out his Son, born of a woman, born under the law, in order that he might redeem those under the law, in order that we might receive the adoption. And because you are sons, God sent out the Spirit of his Son into our hearts, crying out ‘Abba Father’” (Galatians 4:4-6)

P.S. If the last two words of the above verse make you start singing refrains from old Petra songs, it’s OK— I do that too sometimes.

Beyond all this, we are counting the number of angels who can dance together on the head of a pin here. (Please don’t start.)

“Hear O Israel, the Lord your God, the Lord is One.”

I read a book years back that was by a man who grew up in an entirely different religion. He said he got a kick out of ridiculing his Christian friends about their belief in a Trinity. None of them knew why they believed that or how to argue it. His point exactly. You people believe in three gods—get over it!

But then, he said, he took an organic chemistry class in college and learned about a concept called resonances. This is news to me but I never took chemistry of any sort. “Projected in the front of the room were three large depictions of nitrate in bold black and white…different arrangements of the electrons in certain molecules are called ‘resonance structures’…a molecule with resonance is every one of its structures at every point in time, yest no single one of its structures at any point in time…How could something be many things at once? …[in] the subatomic world…things happen that make no sense to those of us who conceptualize the world at a human level.”

And maybe this is where we fit in. We are trying to conceptualize the nature of the Godhead using our own limited experience with othe humans.

(emphasis mine)

So you entertain Nestorianism.

No – the Savior is not a pasted-together arrangement; your first option is not possible.

Again Nestorianism: you can’t chop the Incarnate Word into separate natures. When you refer to Jesus, you mean the eternal Logos as well as the man – He is one, not two.

Basic logic: Jesus is God. Jesus died. Thus, He Who is God died, i.e. God died.

This is why Mary is properly called the Theotokos, the God-Bearer: it was God in her womb.

Nope –

No one has seen God at any time; the only begotten God who is in the bosom of the Father, He has explained Him.

It’s μονογενὴς Θεὸς (mo-no-geh-NACE Theh-OHSS), “only-begotten” or better “uniquely begotten” God.

That’s where the Creed gets its phrase “the uniquely begotten Son of God” – and it expounds on that with “begotten of the Father before all worlds/ages”.

That’s not talking about the humanity; the word is Θεὸς, which is “God”, with no quibbling or deviation. John is saying that it was God – who, yes, was human flesh – who made God known, and that the God Who made God known is begotten.

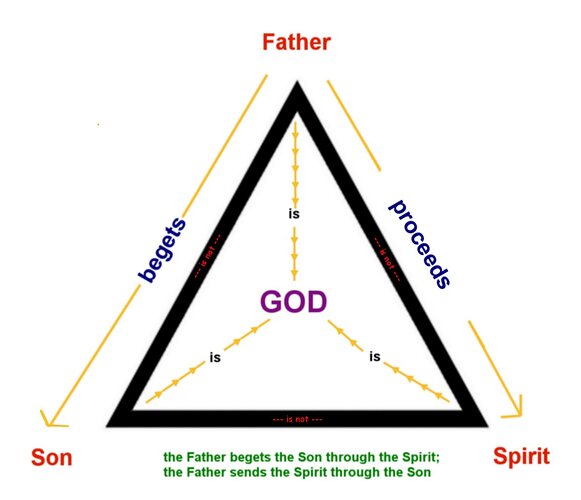

Is contrary to scripture and the Trinity. For review:

The relationships there are all from the scriptures.

Any deviation is not Christian nor biblical.

He is God.

Right, because the Jews had already recognized the plurality within God with the doctrine of the two powers in heaven (with some verging on three).

Jesus is not the Spirit.

God’s divine utterance is call the Logos, and the Logos is God. Either the Logos is not a Person and thus God is not a Person, or the Logos is a Person because God is personal.

You won’t quite commit to the Logos actually being God, but have an almost Gnostic idea of the Logos as some sort of emanation. You verge on modalism, Arianism, Nestorianism, and Gnosticism all at once!

Right, he just goes on to expound the philosophical meaning. /sarc

That’s expanding on the philosophical meaning of πρωτότοκος (prototokos). πρωτότοκος is “the opener of the way”, and the verse above just describes what that means.

That the LXX chose πρωτότοκος to render בְּכוֹר (beh-core) does not limit the meaning Paul makes clear in his exposition.

Plato has little to do with it. πρωτότοκος was used that way by Jewish philosophers before Paul.

The creed doesn’t assume anything, it rests on the Greek.

πρὸς doesn’t indicate mere presence but portrays a dynamic; it suggests not just being “near” or “in the presence of” but a purposeful orientation or communion, implying fellowship, relationship, or even face-to-face intimacy.

Of course not, because John hasn’t gotten quite that far yet. But it is a picture of two entities, God and the Logos.

Ah, the Jehovah’s Witness ploy: drag God down to the level of a human being.

Backwards theology.

It’s not an assumption. Ἐν ἀρχῇ ἦν ὁ Λόγος introduces an entity that has been there always, from the beginning. “Bodily” is an introduced concept that does what you did above, drag the Logos down to a human level.

Besides which, John lived in a milieu where the Logos walking on earth in human form was known, the “second” YHWH-Elohim who met with humans on earth even as the “first” YHWH-Elohim spoke and acted from Heaven. Any Hellenistic Jew reading John’s words could/would have made that connection.

John is saying that the Λόγος is Yahweh.

Ah, modalism.

You manage to mix together quite the impressive array of heresies. People better versed than either of us in the scriptures trashed this point of view long ago – on the basis of the scriptures.

Actually I think you have jumped the gun on that one. I was tempted to make that connection also and dropped it because the same terminology used by The_Omega is used in the hypostatic union.

Nestorianism is the doctrine that there were two separate persons, one human and one divine, in the incarnate Christ.

But the hypostatic union still speaks of two separate natures united in Christ. I must admit, i don’t really think of it that way. But orthodoxy is the hypostatic union.

Yes – and Yahweh in heaven conversed with a very distinct Yahweh on earth, and they both talked as though they regarded the other as a Person. That’s where the idea of “three Persons” comes from, it’s how the scriptures talk about the Three, including how the Father talks about the Son, and how the Son talks about the Father, and how the Son talks about the Holy Spirit.

Yet the Father was still in heaven. You’re now verging on tritheism.

The bizarre thing here is that you’re denying thing that the Creed never denied as though it did, and affirming all the things the Creed says but refusing to commit to what that means.

Which isn’t what the Trinity means.

You’re trying to restrict God to human limitations.

Yet you insist on denying the very doctrine which says that.

Which makes Jesus a liar in practice. Nothing in how He spoke of the Father suggests He was talking to Himself as you describe. And this denies the unity of the Savior, cutting Him into two pieces that could talk to each other – worse than Nestorius ever did!

And so it makes three pieces of God, two of which are not Persons. It ends up with a God made up of part Person and part non-Person.

Not if, as you have it above, one part of Jesus is talking to another part.

No, the Son is talking to the Father, and they are both Persons – that is how the scriptures treat them, which is why the Creed affirms it.

No, they just make it so there really isn’t a Father or a Son or a Holy Spirit, those are just functions. It;s still modalism.

Okay, clearly you have no clue what “Person” even means here. If I’m wrong, then please give the Greek term and explain how it differs from the regular English meaning of “person”.

It looks as though this entire exercise is just another result of people who don’t actually know theology pretending to do theology on the basis purely of English and falling into traps that way because they don’t know what they’re talking about.

Anyone who has actually studied theology would not fall into the grievous and silly errors you keep making about the term “Person”.

Exactly. But to you the Father is just a piece of Jesus, so you end up with Jesus talking to Himself, denying the unity of the Savior.

Given John 1:18, they’re not “mere” semantics, they’re deceptive semantics – as are all your claims that involve the meaning of “Person”.

But you’re denying the very doctrine that Christians have used to say this down the ages. And the only way your view makes sense is if there really isn’t a Father, really isn’t a Logos, and really isn’t a Spirit, those are just the same thing acting in different functions. It’s modalism.

Amen! And what is being argued here is just another attempt to stuff God into a humanly logical box.

Absolutely. In fact apart from the semantics he’s saying the very same things that led to the Trinity doctrine, except when he clearly makes God into pieces some of whom aren’t actually personal.

Cogently put.

I laughed so hard I started coughing – that is a great description.

Along with ones that say things like “So Yahweh rained fire on the earth from Yahweh in heaven”. Yahweh’s in two places, and one of them is in human form . . . .

Yep.

Warfield was right.

Amen.

The definition of “person” does seem to be key here. Though when I look it up I am not sure I buy into theological web of definitions I find.

I would speculatively suggest that a person may be connected with the idea of a timeline of consciousness. Thus the Trinitarian view is that God is capable of more than one such timeline of consciousness. This is particularly meaningful in context of the scientific consensus which rejects the notion of absolute time. And we can add to this the popular notion of different economic roles for salvation. The belief in an eternal father-son relationship suggest there is a lot more to it, however. Though I suppose I would put this under the category of God’s infinite nature.

Yes, because the canon was being established and the seeds of it are in the individual NT books orthodox Christians were using along with the OT scriptures. I just don’t think the earliest Church (aka right after easter) had a full blown trinitarian belief. If you asked Peter if Jesus was full God of full God and not just a divine representative given that power by God, I am not sure what he would actually say. I think the Holy Spirit worked over the first Christians and they spread teachings and wrote things, planting the seeds that would become full trinitarian belief.

The two powers view is quite interesting. A subset of Jews seemed to have had binitarian views while some others just saw the second power as a creation of God imbued with his authority and power. I think we sometimes we go overboard in how we understand early Jewish monotheism.

It’s the only beginning of Jesus in Mark. The Spirit descends down on Jesus and calls him the Son of God. At the end the temple veil rips signaling (I think) God’s spirit leaving the temple/Jews and the centurion says truly this was God’s son. Mark likes his sandwiches (intercalations) and that ABCBA pattern. I think it’s a valid interpretation of Mark though certainly not beyond question.

To me that obviously follows from a belief in creation ex nihilo and shows up throughout scripture. I found a short tale we read in Bible study related to this by Nichola of Cusa (1401-1464) who was a philosopher, theologian, bishop and cardinal. He wrote a work called De Deo Abscondito which had a fictional dialogue between a pagan and a Christian. A pagan approaches a Christian he finds deep in prayer. He asks the Christian to identify the God he worships.

The Pagan spoke: I see that you have most devoutly prostrated yourself and are shedding tears of love—not hypocritical tears but heartfelt ones. Who are you I ask?

Christian: I am a Christian.

Pagan: What are you worshiping?

Christian: God.

Pagan: Who is this God whom you worship?

Christian: I don’t know.

Pagan: How is it that you worship so seriously that of which you have no knowledge?

Christian: Because I am without knowledge of Him, I worship Him.

“The paradox is stunning– only a God who cannot be fully comprehended, who is inexpressible Truth, could be the true God and worthy of our adoration.” – Baglow

Exodus 3:13-14, Isaiah 55:8-9, Job 37:5, 23, Rom 11:33-34, Psalm 145:3 and even 2 Peter 3:8–9.

Vinnie