Actually this reply is intended not just for @Nuno, but for many others as well.

IMO, the range of opinions expressed already, relative to classroom content in public education, supports my statement that this problem is insoluble. I can’t respond to everyone, unfortunately, but let me espond to this, from Nuno:

“Unfortunately I must vehemently disagree with this point when it comes specifically to ID or similar topics - the bar of what is taught in science classes must be no lower than having the material be accepted as science by at least a majority of scientists. Otherwise it simply is not science, period.”

I’d be surprised if this view were not shared by many in science education. It’s a reasonable standard, but the problem remains. Nuno’s reference to a “majority of scientists” implies that conclusions in science are reached democratically, which is partly true, but those eligible to “vote” in that election are a tiny subset of the larger population. Whether or not science is democratic, science education in a democratic republic ought to be democratic, as far as possible. Indeed, this was perhaps the strongest argument of William Jennings Bryan during the Scopes era—namely, that “the hand that writes the paycheck rules the schools.”

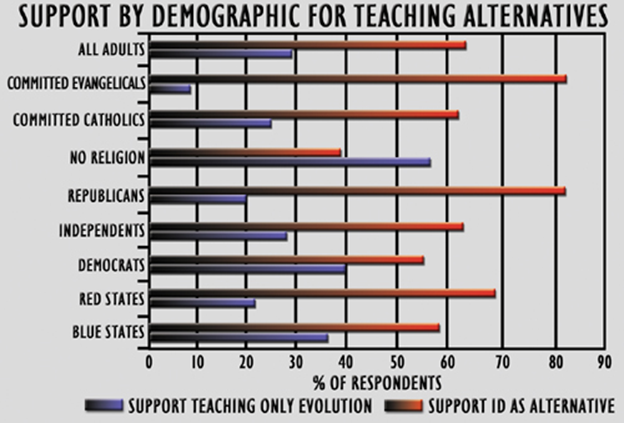

Let me point to the results of a fascinating poll, carried out by Cornell University experts just a few months before the Dover trial:

(graph taken from Geotimes — September 2005 — Evolution & Intelligent Design: Understanding Public Opinion)

For me, this is an eye-popping “wow.” In every single demographic group, cutting across political lines, save one—those who stated that they have “no religion”—there was very strong support for teaching ID as an alternative to evolution. I’ve already said that I don’t believe ID really is a scientific alternative to evolution, which would have complicated my own response to the pollsters, but this does mean something.

One thing it means, IMO, is that the presently received interpretation of the First Amendment, in which extra-Constitutional language about “a wall of separation between church and state” (from a letter by President Jefferson, who did not write the Constitution), is used to determine the meaning of the disestablishment clause in the Constitution. This state of affairs profoundly shapes the evolution controversy in public schools, making it essentially insoluble.