Yes. I wasn’t aware that this is in dispute. I don’t know anyone who claims that Jesus is the Father (except for Modalists). Does this relate in any way to the current discussion about whether theos normatively refers to the Father in the New Testament?

But he does say, “In passage after passage, the deity of Christ shines through the pages of the New Testament.”

Well yes, he’s a Trinitarian, it’s no surprise that he says this.

While waiting for Jonathan’s reply, I’ll throw in my agreement with Reggie. It looks like Pliny clearly shows that Jesus was being worshipped as one would worship God (or “a god” in Pliny’s Greco-Roman realm). Hurtado affirms that the Christians did this because they thought Jesus was God.

Sorry to keep you. Fortunately this post can be briefer than I expected, since we’ve already reached agreement on a number of issues.

-

Although the common meaning of θεός is “god”, it has a wider range of meanings which do not mean "god ( and which include the adjectival sense “divine”). This usage is widespread in Greek literature, the Old Testament (LXX), and Second Temple Period literature, and is also found in the New Testament. Jesus himself uses one such meaning, in John’s gospel (the only reason why I cited this usage by Jesus was to demonstrate that θεός does not always mean God; it doesn’t have any other relevance to John 1:1).

-

The use of θεός in John 1:1c is not necessarily identifying Jesus as God, contrary to what you originally thought. Not only can it be understood to mean “divine”, the grammar alone does not get you to “God”. As you have said, “he grammar, on its own, does not get you to ‘God’ and leaves room for ‘divine’”. Consequently, as you have noted, the numerous commentators who read it as “God”, do so as an interpretive decision based on their interpretation of other verses first (as they state explicitly). Even though they don’t believe the Synoptic gospels present Jesus as God, they interpret some passages of John’s gospel as presenting Jesus as God, and therefore conclude that the logos is being called God in John 1:1. This is an interpretive conclusion based on what they believe John’s theology to be.

-

Benjamin Sommer’s “multiple bodies” and “Hindu avatar” theory of conceptions of God in ancient Israel and fourth century to early medieval Judaism, have no relevance to our understanding of God in the New Testament, much less our understanding of John 1:1.

We won’t need to revisit these issues. Now I’ll answer your firebreak question.

In what sense do you think John thought Jesus was? How high was John’s christology in your view? You will need to explain this as you have been ambiguous by the word “divine” so far, since this word can also be taken to mean “literally God”. What does John mean when he calls Jesus “divine”?

By “divine”, I mean Jesus was divine in origin; he was the son of God. This placed him in a unique relation to God. Additionally, he was given unique authority, unique titles, a unique role, and God worked through him uniquely, specifically because he was the son of God, and therefore God’s representative on earth. He was a human of divine origin, who was appointed as the unique agent of God.

Now to other matters.

Point one.

I gave you the Greek of John 1:1.

John 1:

1 Ἐν ἀρχῇ ἦν ὁ λόγος, καὶ ὁ λόγος ἦν πρὸς τὸν θεόν, καὶ θεὸς ἦν ὁ λόγος.

I asked this question.

Do you understand why translating “theos” as “God” the first time, and “divine” the second time, is based on the actual Greek grammar? If you do, please provide the grammatical explanation.

You said you can barely read the Greek “I certainly can’t answer your question about it”. So now I’ll explain.

-

The first grammatical reason for reading theos as “God” the first time and “divine” the second time is based on the fact that the two instances are grammatically different. As you know, one is τὸν θεόν (using the article), and the other is θεὸς (anarthrous). This alone is warrant to translate them differently, and this is why many people appeal to the translation “God” for τὸν θεόν and “a god” for θεὸς.

-

However, the grammatical information does not stop there, since θεὸς is not simply anarthrous, it is anarthrous qualitative predicate nominative. The qualitative sense of θεὸς here indicates that we are dealing with θεὸς as an adjective, not a noun. This is why the NET arrived at the translation “fully God”, to preserve the adjectival sense of θεὸς in the clause, while also preserving the theological conclusion that the logos is “God” in some (undefined), sense.The footnote makes it clear that they believe John was writing as a Trinitarian; “This points to unity of essence between the Father and the Son without equating the persons”. They assume that John actually believed that God was more than one person (which is certainly questionable).

-

So the anarthrous qualitative predicate nominative argues strongly against “a god”, and that’s even before we get into the more awkward consideration of the fact that “a god” means we now have two gods (a theological position which would then have to be somehow harmonized with the Second Temple Period context, and the content of the New Testament itself). However, in addition to the fact that the second instance of θεὸς is anarthrous, and in addition to the fact that it is also qualitative, we also have lexical evidence of θεὸς (nominative), placed before a vowel, being used specifically to mean “divine” (as I have discussed extensively with “Bill Smith”).

So these are the three grammatical arguments for translating the second θεὸς differently to the first.

- It’s anarthrous

- It’s anarthrous qualitative predicate nominative

- It’s anarthrous qualitative predicate nominative before a vowel

In addition, there are lexical reasons for not translating it as “God”, namely that theos in the New Testament virtually exclusively refers to the Father. Trinitarian scholar William Hasker notes this.

“First, “God” is used to designate Yahweh, the God of the Old Testament, who was known to Jesus as Father and whom he taught his followers to address as Father. This is the standard usage of “God” throughout the New Testament, as can be verified by a cursory reading of the texts.” [1]

Trinitarian scholar Murray Harris spends seven pages examining all the uses of theos in the Synoptics, John, Acts, Paul’s letters, Peter’s letters, Hebrews, James, Jude, and Revelation, and concludes thus.

“When (ὁ) θεός [God] is used, we are to assume that the NT writers have ὁ πατήρ [the Father] in mind unless the context makes this sense of (ὁ) θεός [God] impossible.” [2]

He notes that there are 83 instances of θεός in John, and only two of them cannot refer to the Father.

“Of these 83 uses of θεός, the only places where the word could not refer to the Father are 1:1 (second occurrence, referring to the Logos); 1:18 (second occurrence, referring to μονογενὴς ;-see chapter III §§B-C); 10:34-35 (both plurals); and 20:28 (addressed to Jesus).” [3]

Another lexical reason for it is that we have evidence from Second Temple Period Judaism that the anarthrous θεός was used to differentiate between “the one true God”, and anything else which could be called θεός but was not actually God. Philo describes it this way.

“There is one true God only: but they who are called Gods, by an abuse of language, are numerous; on which account the holy scripture on the present occasion indicates that it is the true God that is meant by the use of the article, the expression being, “I am the God (I);” but when the word is used incorrectly, it is put without the article, the expression being, “He who was seen by thee in the place,” not of the God (t**ou Theou), but simply “of God” (Theou**);” [3]

This is even more significant given the fact that Philo used θεός to refer to God’s Word (which he of course wrote as Logos). Philo was perfectly happy calling the Logos θεός (without the article), because to Philo the Logos was divine; it was God’s reason, wisdom, thought, and word, the power with which God created the world. Philo spoke of the Logos being with God, and being θεός. But for Philo the Logos was not an independent being, nor a hypostasis of God, nor a person in a multiple-person God. So we have a first century witness to the fact that the anarthrous θεός was used in Second Temple Period Judaism (even in the first century), to refer to that which was not the one true God, but that which could be called “god” or “divine” in some sense. This lexical understanding was preserved within the early Christian commentators. I have already cited Origen saying exactly the same thing. No Origen didn’t believe Jesus was God, he believed Jesus was a divine being separate from and second to God, and who had a different nature to God.

However, there are also theological reasons for not translating it as “God”. Murray, whom I quoted earlier, accepts the translation “the Word was God” only with strong caveats.

“But in normal English usage “God” is a proper noun, referring to the person of the Father or corporately to the three persons of the Godhead. Moreover, “the Word was God” suggests that “the Word” and “God” are convertible terms, that the proposition is reciprocating. But the Word is neither the Father nor the Trinity. Therefore few will doubt that this time-honored translation needs careful exegesis, since it places a distinctive sense upon a common English word. The rendering cannot stand without explanation.” [4]

Trinitarian scholar Charles Irons explains it this way, preferring the translation “divine”.

“I hesitate to say “Jesus is God,” nor would I say “Jesus is not God”. Instead, I prefer to say, as the New Testament says, that “Jesus is the Son of God.” Although it is possible to construe it in a valid sense, I am cautious about the statement “Jesus is God,” because the name “God” (with the definite article, ho theos) most frequently and properly refers to the Father. “Jesus is God” could be taken to mean “Jesus is the Father,” which would be modalism. On the other hand, following John 1:1, we have strong precedent for saying that “Jesus is divine” (theos as anarthrous qualitative predicate nominative).” [5]

Note that last sentence; he takes John 1:1 as strong precedent for saying “Jesus is divine”. Thanks Charles! You will note that neither Murrary nor Irons makes the theological argument you do, that it’s ok to say “the Word was with God and the Word was God” if God has multiple persons. On the contrary, they rightly say that this phrase causes problems when read as referring to a God with multiple persons, precisely because it confuses the persons.

As I see it, arguing that you can get around contradiction A by positing an additional contradiction B, is just piling confusion on confusion. It’s these kinds of ad hoc arguments which really expose Trintarian doctrine to serious criticism, not the least of which is logical incoherence. This incoherence has always been recognized by Trinitarians, and is captured well in the phrase “The Father is God, the Son is God, and the Holy Spirit is God, yet there are not three Gods but one God”. The phrase leads us to a logical conclusion and then takes an abrupt u-turn shouting “No, don’t go there!”. It’s not a good look.

Now I’ll answer this question of yours.

At this point, you have not yet defined what you think “and the Word was divine” means. What do you think John would mean by such a statement? That the Word is eternal and the medium through which all creation happened?

I explained it previously, but that was a while ago. It’s the word of God; the davar in Hebrew. The word of God, which represents His wisdom, reason, and power. We are told in Genesis 1 that God created by speaking, and in Psalm 33 the word of God is described explicitly with a bold anthromophism as “the breath of His mouth”. We find that same language in Philo, and we find it right here in John.

Keener (who of course believes Jesus is God and that Jesus is called God here), puts it this way.

"The Old Testament had personified Wisdom (Prov 8), and ancient Judaism eventually identified personified Wisdom, the Word and the Law (the Torah). By calling Jesus “the Word,” John calls him the embodiment of all God’s revelation in the Scriptures and thus declares that only those who accept Jesus honor the law fully (1:17). Jewish people considered Wisdom/Word divine yet distinct from God the Father, so it was the closest available term John had to describe Jesus.

1:1–2. Beginning like Genesis 1:1, John alludes to the Old Testament and Jewish picture of God creating through his preexistent wisdom or word. According to standard Jewish doctrine in his day, this wisdom existed before the rest of creation but was itself created. By declaring that the Word “was” in the beginning and especially by calling the Word “God” (v. 1; also the most likely reading of 1:18), John goes beyond the common Jewish conception to imply that Jesus is not created (cf. Is 43:10–11)." [6]

Virtually all of this is what I would say. I part ways with Keener only when he says that John 1:1 is clearly saying that the logos was a pre-existent person, and that John is deliberately breaking with the Jewish tradition.

Köstenberger puts it this way.

"The term “the Word” conveys the notion of divine self-expression or speech (cf. Ps. 19:1–4). The Genesis creation account provides ample testimony to the effectiveness of God’s word: he speaks, and things come into being (Gen. 1:3, 9; cf. 1:11, 15, 24, 29–30). Both psalmists and prophets portray God’s word in close-to-personified terms (Ps. 33:6; 107:20; 147:15, 18; Isa. 55:10–11), but only John claims that this word has appeared in space-time history as an actual person, Jesus Christ (1:14, 17).

Most critical in this regard is Isaiah’s depiction of God’s word as going out from his mouth and not returning to him empty, but as accomplishing what he desires and achieving the purpose for which he sent it (Isa. 55:11; cf. 40:8). In this passage Isaiah provides the framework for John’s “sending” Christology, which presents Jesus as the Word sent by God the Father who pursues and accomplishes his mission in obedience to the one who sent him. This sender-sent relationship, in turn, provides the paradigm for Jesus’ relationship with his followers (cf. esp. 17:18; 20:21–23; see Köstenberger 1998b)." [7]

I can agree with every word of that. Arnold describes it thus.

"Was the Word (1:1). Echoes of the creation account continue here with allusion to the powerful and effective word of God (“And God said, ‘Let there be light,’ and there was light”; Gen. 1:3). The psalmists and prophets alike portray God’s word (logos) in almost personal terms (e.g., Ps. 33:6; 107:20; 147:15, 18; Isa. 55:10–11). Isaiah, for instance, describes God’s “word” as coming down from heaven and returning to him after achieving the purpose for which it was sent (Isa. 55:10–11). John takes the prophetic depiction of God’s word in the Old Testament one decisive step further. No longer is God’s word merely spoken of in personal terms; it now has appeared as a real person, the Lord Jesus Christ (cf. 1 John 1:1; Rev. 19:13).

While the primary source of John’s depiction of Jesus as the Word is the Old Testament, his opening lines would resonate with his Greek-speaking audience. In Stoic philosophy, for instance, logos was used to refer to the impersonal principle of Reason, which was thought to govern the universe. It is a mark of John’s considerable theological genius that he is able to find a term (“the Word”) that is at the same time thoroughly biblical—that is, rooted in Old Testament teaching—and highly relevant for his present audience." [7]

Again, I would say exactly the same. You can see that calling the logos “theos” does not in any way require the logos to be a person, nor does it require the logos to be a person in a God who is one being with multiple persons.

This point one of mine addresses the argument in your three points which concluded “These contextual considerations rule out anything less than the Word being, literally, God”. While I’m here I might as well ask you why you interpret ὁ λόγος as a person, since we both know that the Greek word ὁ λόγος does not mean a person anymore than the English word “word” means a person.

This addresses everything in your previous post. Now I’ll move to your latest post. There’s a lot less to deal with in this one.

Point two.

You conceded Sommer to me, which was good of you, so that leaves this.

The works of Segal and Boyarin collectively demonstrate that Judaic monotheism wasn’t as simple “one God one person one everything” – and that the multiplicity of the persons of God, not just the bodies, was known and not at all heretical in pre-Christian Judaism. In that sense, there is no contradiction at all in John 1:1 since it can be understood as referring to the multiplicity of God’s person. And even if there was absolutely zero multiplicity of God’s person before Christianity, which there surely was, then this could be explained as a new Christian interpretation and we can still understand John 1:1 as referring to God’s multiplicity and thus not have to deal with a contradiction.

I will have more to say on Segal and Boyarin later (for now, on Boyarin, I recommend you read this, which notes that his case is based only three texts). I have several of Boyarin’s works but I haven’t read them all (I am only in the middle of “The Jewish Gospels”). I’m more familiar with Segal. However, here are a few points to start with.

-

The New Testament uses none of the “multiplicity of persons” language which we see in texts which actually are referring to a multiplicity of persons

-

The New Testament shows clear evidence that many Jews considered Jesus’ claim to be the son of God, to be deeply heretical; where is the evidence that they understood he was referring to himself as one of the persons in a multi-personal God, but had no problems with that?

-

Claiming that John 1:1 can be understood as referring to a multiplicity of persons is one thing, but demonstrating that this is what he meant, is quite another

-

To claim that a multiplicity of person was a Christian innovation is of course an even more difficult challenge to meet, but either way at some point you need to address the fact that the overwhelming use of θεὸς in the New Testament refers to one person, the Father, and the fact that God in the entire Bible is never referred to as “they”

You quoted this.

It will also be important to quote Richard Hays again when he says “Daniel Boyarin is another scholar who has provacatively destabilized conventional beliefs about what first-century Jews could and could not have believed about the multiplicity within the divine identity.”

I suggest strongly that you read closely what Hays is and isn’t saying about Boyarin, because by the time I have finished reading Boyarin I think you’ll be disappointed in just what he does and doesn’t prove. I’ll give you a hint; the word “provocatively destabilized” is a polite way of saying Boyarin has made extremely bold claims which have convinced very few people at all, and only highly qualified assent has been given to any of his claims.

Point three.

I asked “Do you understand that the frequency with which a Greek word is translated in an English Bible has absolutely no relevance to whether or not the word has a particular meaning in a specific verse?” You responded thus.

Actually, it most certainly has relevance. If we know the standard usage of a word in a language, then we must further know that we should only abandon understanding it in its primary sense if there is reason to do so.

No. The frequency with which an English translation has translated a word, does not give us any information about how that word is used in a specific context. Think about this for a minute; we’re talking about an English translation of the word. What is more important is how the author uses it in the original source language text. However, even if an author uses a particular word 99 times with one meaning, this does not provide us with any information on how they are using it in another passage, unless they’re using it in exactly the same semantic and grammatical context. How many times can you find θεὸς in John, used as anarthrous qualitative predicate nominative before a vowel? You know that John uses θεὸς 81 times to refer to the Father, so are you seriously going to suggest that the other two times, we must assume is is also referring to the Father? Surely you can see what a mess your own rule will get you into.

Point four.

I quoted Daniel Wallace saying this.

“The list of passages which seem explicitly to identify Christ with God varies from scholar to scholar, but the number is almost never more than a half dozen or so. As is well known, almost all of the texts are disputed as to their affirmation—due to textual or grammatical glitches—John 1:1 and 20:28 being the only two which are usually conceded without discussion.” [8]

You were very excited by this.

Incredible. So the text I cited is literally not even debated amongst scholars to clearly identify Jesus with God. This isn’t even an overwhelming majority in scholarship, this is an absolute consensus.

I hate to break it to you, but you’re wrong on this. After the sentence which concludes “John 1:1 and 20:28 being the only two which are usually conceded without discussion”, Wallace has a footnote which flatly contradicts your enthusiastic reading of his words. He says this.

“Even here there is debate, however.”

So in fact there isn’t a single undebated verse, there are only two which everyone agrees apply θεὸς explicitly to Jesus, and even the meaning of those two is debated.

Conclusion

I suggest that you give some thought as to why Hurtado adamantly stops short of saying Jesus was understood to be God by his earliest followers, and why He says that theos is applied to Christ in John’s gospel but does not say this means Jesus is God. He was pressed firmly on these points by Ben Witherington, and his response is revealing. Here is the exchange.

BEN: In your second chapter you say at one juncture (p. 73) that Jesus is treated in ways that liken him to God. Wouldn’t be better just to say, as Bauckham does, that in ways we don’t full grasp Jesus was considered part of God’s very identity, meaning of course that God was complex, involving more than one personal entity. This latter view seems to me to do better justice to the fact that: 1) while the term theos in the NT almost always means the one Christians call God the Father, nevertheless, even in our earliest source, Paul; 2) Jesus is called God in Rom. 9.5, as Metzger long ago showed, and in a text like Phil. 2.5-11 as well (not to mention in five other places in the NT— see Silva’s book). In other words, even in the earliest part of the NT era, there was beginning to be a reformulation of the meaning of the word theos among even some Jewish Jesus followers. Jesus is not merely likened to God he has begun to be included in what we call the Godhead. How do you respond? I must add as an addendum, that I find the tap dance done by Jimmy Dunn on this very matter unconvincing when it comes to Paul’s beliefs and expressions.

LARRY: I understand the desire to explore the relation between first-century Christological claims and subsequent formulations, but I also think that we should be cautious in respecting the differences, and cautious also about reading earlier formulations too much with regard to how they line up with subsequent ones. In my book, God in New Testament Theology (Abingdon, 2010), I discuss how Jesus is programmatically included in early Christian discourse about “God”, and also in the worship directed to “God.” Sure, at least in John 1:1 and 20:28, “theos” is applied to Jesus. But Jesus’ divine status is rather consistently defined with reference to “God” (“the Father” in Pauline and Johannine terms). Later (as I judge it), Christians took up questions about “ontology”, using Greek categories of “being”, and this entailed controversies such as the “Arian crisis” of the fourth century. But I try to confine my discussion of NT discourse to the categories in that discourse, and I don’t think it helpful to impute the later (albeit, perfectly reasonable) terms such as “Godhead,” divine “persons,” divine “substance” etc., into these texts. I’d rest with simply saying that the NT makes Jesus integral to any adequate discourse about “God” and to any adequate worship of “God.” Christian theology must do more than simply echo NT formulations, of course. But that’s a theological task, whereas my work is more concerned with historical analysis.

This reply is longer than I wanted it to be (just over 10 pages), but there was a lot to get through. If you think I’ve missed anything, or you want me to go over anything in more detail, just let me know.

[1] William Hasker, Metaphysics and the Tri-Personal God (OUP Oxford, 2013), 246-347.

[2] Murray J. Harris, Jesus as God: The New Testament Use of Theos in Reference to Jesus (Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2008). 47.

[3] Philo, “On Dreams” 1.229, Charles Duke Yonge with Philo of Alexandria, The Works of Philo: Complete and Unabridged (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 1995), 385.

[4] Murray J. Harris, Jesus as God: The New Testament Use of Theos in Reference to Jesus (Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2008). 69.

[5] Charles Lee Irons, Danny Andre Dixon, and Dustin R. Smith, “A Trinitarian View: Jesus, the Divine Son of God (Irons),” in The Son of God: Three Views of the Identity of Jesus (Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2015), 20.

[6] Craig S. Keener, The IVP Bible Background Commentary: New Testament (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1993), Jn 1:1–18.

[7] Andreas J. Köstenberger, “John,” in Commentary on the New Testament Use of the Old Testament (Grand Rapids, MI; Nottingham, UK: Baker Academic; Apollos, 2007), 421.

[8] Daniel B. Wallace, Granville Sharp’s Canon and Its Kin: Semantics and Significance (Peter Lang, 2009), 27.

I was actually saying the very opposite, I interpret it as saying that Jesus was worshipped ‘like’ a god, not ‘as’ a God. I also thought I made that clear.

Could you quote him on this? It would be useful.

What’s the distinction?

You would not worship ‘God’ as to a god, that would imply he wasn’t a god.

Pliny is being polemical when he says “as to a god” since he saw the Christians worshipping Jesus like one would worship God, but in Pliny’s reckoning he was just a man who was killed. Thus he says “as to a god” implying he wasn’t actually one.

He was also worshipped by the Magi (Matthew 2)

Why does it have to be explicit? If something is contested why is it automatically waved away? Look at the resurrection, and many other examples.

It doesn’t have to be explicit, and just because it is contested doesn’t mean it is automatically waved away. But it does mean that when I contest it, I’m in good company.

Yes, the Romans didn’t believe Christ was any kind of god, but the Christians sang a hymn to Christ as to a god. Who else would you sing a hymn to?

A look at "PSALMS, PHILIPPIANS 2:6-11, AND THE ORIGINS OF CHRISTOLOGY"

By ADELA YARBRO COLLINS of Yale University Divinity School

will be very instructive in this matter

But we might have to dismiss it outright if the author is a Trinitarian.

It appears to me that there are significant issues with the way you’re using some of those quotations. The first section of my reply will be devoted to precisely this, as it takes up a considerable part of your comment. Then, I will deal with other issues. Even the three things you stated we “agree on” are way exaggerated past what I said (or I’m pretty sure I made clear) earlier, which I will point out in the second section of my reply onwards.

Quotations and scholarly opinions

I will repost Richard Hays’ quote before I quote your response, which in fact totally skewed what Hays said. To remind us, this is what Hays said;

Daniel Boyarin is another scholar who has provacatively destabilized conventional beliefs about what first-century Jews could and could not have believed about the multiplicity within the divine identity.

Your response:

I suggest strongly that you read closely what Hays is and isn’t saying about Boyarin, because by the time I have finished reading Boyarin I think you’ll be disappointed in just what he does and doesn’t prove. I’ll give you a hint; the word “provocatively destabilized” is a polite way of saying Boyarin has made extremely bold claims which have convinced very few people at all, and only highly qualified assent has been given to any of his claims.

In fact, this entirely misunderstands Hays’ quote. I thought at first you had his book Reading Backwards, but now I significantly doubt this. Hays wrote that in the preface of his book, and if you actually read the preface, he spends several pages detailing scholars, one by one, who have had a significant impact on his understanding on the biblical texts, ancient world, etc. Every time he notes one of these scholars, he puts their name in bold and then details their contribution. This is exactly what he did for Boyarin here, anyone who has read this section where Hays wrote it unequivocaly understands Hays is writing that Boyarin has demolished the idea that the multiplicity of the person was not therein 1st century Judaism. In fact, since I thought Hays quote was obviously clear, I actually did not quote the full section Hays wrote on it in his preface. Here is Hays entire quote (bold not mine):

Daniel Boyarin is another scholar who has provocatively destabilized conventional beliefs about what first-century Jews could and could not have believed about multiplicity within the divine identity. Approaching the question from his comprehensive knowledge of rabbinic and other Jewish texts, he has sought to demonstrate that a particular sect of “binitarianism,” heavily indebted to exegesis of Daniel 7, was widespread in Jewish thought in the ancient Meditteranean world. On his reading, the rabbinic attempt to stigmatize such beliefs was a later development. Boyarin’s illuminating interpretation of the prologue of the Fourth Gospel underlies part of my argument in chapter 5 of the present study.

Hays speaks very well of Boyarin’s work, and lists it among the works that has heavily influenced his understanding, and when he says “provocatively destablizied”, he is doing nothing short than stating the fact that Boyarin’s work has had monumental influence and has convinced a wide number of scholars, including Hays himself. You should read the entire preface of Hays book.

You then, at the end of your comment, devote close to a tenth of your reply to quoting a discussion between Ben Witherington and Larry Hurtado. However, you completely misunderstood what Hurtado said if you think he was saying Jesus is never said to be God in the Bible. We’ll see that’s unequivocally false in a second. Hurtado is obviously expressing restraint pver using modern terminology like “godhead”, divine “persons”, “substance” etc to biblical concepts that did not know those specific terms, since they could carry modern baggage with it not found in those particular texts. It’s obviously the terminology that is Hurtado’s issue in the quotation you offered. He also never denies Jesus is God in John 1:1 which is clear. Just a day or two ago, I watched a lecture by Larry Hurtado on his new book Destroyer of the Gods: Early Christian Distinctiveness in the Roman World (2016). In the Q&A session, he was asked the following by a questioner, and he provided the subsequent response (I will provide the timeline in the lecture where this happens and then post the lecture):

Questioner (1:09:04): Well while we’re on that subject, when we see Jesus being referred to as “the Lord” ('o kyrios) in the New Testament should we understand that to be meaning Jesus is identified as yod he vau he as Trinitarians believe or simply “master” as Unitarians believe?

Hurtado (1:09:21): It depends on the context. There are passages in which the term 'o kyrios in Greek and the term adon in Hebrew have a wide – as the term Lord does for example if you perceived trial, as you may name, in a British court you would probably address the judge as ‘My Lord’, not ‘Your Honor’. And of course we have lords aplenty, whole houses of lords in the British Parliament. So the term ‘Lord’ can mean a variety of things and as it can in Greek so you have to look at the sentences. There are sentences in the New Testament I think when Jesus is referred to “as the Lord teaches” and so and so they well mean simply “the master”, but there are important passages, identified in particular by my friend whose here tonight Dave Capes where Old Testament passages that, ugh, inarguably refer to God – yod he vau he – are applied to Jesus, you know, classic one, “Whosoever calls upon the name of the Lord Jesus Christ shall be saved”, that is of course a phrasing that is lifted from the Old Testament, “Whosoever calls upon the name of Yahweh shall be saved”, but in the New Testament amended to be a cultic invocation to Jesus by name. So certainly in early Christian devotional practice, which is what I’ve dined on quite a lot for the last twenty-five years, early Christian devotional practice Jesus functions very similar in the way to which God functions in devotional practices.

Hurtado clearly thinks Jesus is called God in the New Testament, and of course he restrains in the way that any careful scholar restrains from making outright declarations (which is what you seem to be looking for). I invite you to go to Larry Hurtado’s blog and ask him whether or not he thinks Jesus ever calls Himself God in the Gospel of John. You will be disappointed.

Then, there’s Daniel Wallace’s words. You make a good point, but miss something very important:

I hate to break it to you, but you’re wrong on this. After the sentence which concludes “John 1:1 and 20:28 being the only two which are usually conceded without discussion”, Wallace has a footnote which flatly contradicts your enthusiastic reading of his words. He says this.

“Even here there is debate, however.”

So in fact there isn’t a single undebated verse, there are only two which everyone agrees apply θεὸς explicitly to Jesus, and even the meaning of those two is debated.

But debate by who? Clearly, if Wallace is so confident as to assert that two are almost always conceeded without discussion, this is an obvious overwhelming majority. It’s evident, by any rational analysis, that your position belongs to a tiny tiny minority of scholars. To ask, which sources does Wallace cite in that footnote?

Other issues

So I’ve addressed all that, let’s move on to the more general issues here. Firstly, let’s talk about the three points you wrote we agree on. In fact, only the third point you mention is exactly correct. The first one is obviously exaggerated, we’ve seen that non-God meanings of theos are exhibited in a range of texts, but still, it is overwhelmingly outnumbered by God meanings. In the Gospel of John, out of more than 80 uses of theos, you’ve only been able to point to one text that actually means something besides God. That means the percentage in John where theos means God is in the range of 98-99% of the time. I can confidently assert that easily, 95% of uses of theos means God. So, this is what we agree:

The meaning of theos as ‘divine’, and other non-primary meanings besides God, is within the legitimate lexical range of the meaning of the Greek term and it is witnessed in a variety of texts.

That is completely fair. Regarding point 2, again I agreed that ‘theos’ can be grammatically read as ‘divine’, (just like ‘a god’ is, which I will also discuss in a second) but in fact you make some points on the Synoptics which are simply incorrect. And even in regards to John 10:34, I made some very important points that you did not address in your most recent response that clearly distinguishes it from usage from other uses of theos, especially John 1:1. Here is what I wrote earlier:

Yes, Jesus used ‘theos’ here in a way that does not mean ‘God’. I have already addressed this at length previously, so while waiting for your next response to my other comments, I will make another point regarding John 10:34 that clearly distinguishes it from the other uses of ‘theos’ in the Gospel of John, especially John 1:1. First of all, ‘theos’ in John 1:1 is clearly singular (theos), whereas in John 10:34, it is actually plural (theoi), so in fact ‘theos’ in its nominative masculine singular form never appears in John 10:34. All uses of ‘theos’ (not theoi) in John clearly mean ‘God’. Secondly, in John 10:34, Jesus is directly drawing from Psalm 82:6, an OT text that does not refer to God, rather it refers to us humans. So, taking into account the context of John 10:34, it clearly couldn’t mean ‘God’, the context rules it out, something very distinguishing from John’s other uses of ‘theos’, especially in John 1:1. So, this will not be enough to salvage your thesis.

This is very important, since in fact even with John 10:34, you have not produced a single time where theos (singular) is ever used in a regular, sober context in John’s Gospel and it does not mean ‘God’. This has significant implications, and by simply probability alone and taking into account the continuity of John’s use of theos, we clearly would expect it to mean God in John 1:1. That you did not address the points regarding John 10:34 I made is important.

Furthermore, you also write this after quoting Charles Iron:

On the contrary, they rightly say that this phrase causes problems when read as referring to a God with multiple persons, precisely because it confuses the persons.

As I see it, arguing that you can get around contradiction A by positing an additional contradiction B, is just piling confusion on confusion. It’s these kinds of ad hoc arguments which really expose Trintarian doctrine to serious criticism, not the least of which is logical incoherence. This incoherence has always been recognized by Trinitarians, and is captured well in the phrase “The Father is God, the Son is God, and the Holy Spirit is God, yet there are not three Gods but one God”. The phrase leads us to a logical conclusion and then takes an abrupt u-turn shouting “No, don’t go there!”. It’s not a good look.

In fact, Charles Iron, in the quotation you produced, never says that there is any “confusion of the persons” here. There obviously isn’t, it’s a remarkably simply phrase. “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.” The the Word was in the beginning, and the Word was with (implying a distinction) God (the Father) in the beginning, and He was (one with) God. There’s no confusion on my reading. Again, as we’ve seen earlier, Segal and Boyarin’s work, as well as the reception of their work, removes any need to consider this a contradiction. A contradiction is when two things cannot both be true at the same time, but there is a very clear way which this passage can be true on my reading. Trying to force a contradiction on my reading wont get you anywhere.

I also have to mention that you might have befuddled at one point. You send me to this review of Boyarin’s book … you have the wrong book there bud! Daniel Boyarin’s classic book on this issue is Border lines: the partition of Judaeo-Christianity. His more recent book, The Jewish Gospels is not the one I’m referring to, which is the subject of the critique you sent. Obviously his book Partition is what is all the buzz in academia. By the way, when I cited Hays quote above, he provided a footnote to Boyarin’s work, and when I checked the footnote, it went nowhere else than Boyarin’s book Partition, not The Jewish Gospels which I am already aware has been critically taken by Hurtado and another scholar Hurtado cites. I will read this review (which is on a blog I might note!) after completing this response.

I have already cited Origen saying exactly the same thing. No Origen didn’t believe Jesus was God, he believed Jesus was a divine being separate from and second to God, and who had a different nature to God.

Actually, you didn’t cite Origen saying this at all. You referred me to a near 40-year-old German commentary that has affiliations with Robert Funk that says Origen said Jesus was divine. They provided a citation to Origen, but my quick perusal of this citation did not find confirmation. Surely you can directly quote from Origen himself if he said this instead of relying on some old German commentary?

You claim Origen does not think Jesus is God, but I’m almost quite certain he does, or at least something radically different from your view. I’ve read his entire Against Celsus. Origen if I’m not mistaken, historically converted Bostra (an adoptionist) from his view of Jesus becoming only divine after the baptism to orthodoxy. NOTE: My initial suspections have been confirmed, Origen thought Jesus was God. Read this link and the citations from Origen they provide. Origen clearly thought Jesus was a pre-existent divinity, perhaps subordinate to the Father but still God.

No. The frequency with which an English translation has translated a word, does not give us any information about how that word is used in a specific context. Think about this for a minute; we’re talking about an English translation of the word. What is more important is how the author uses it in the original source language text.

That is not what I was talking about at all! I was precisely citing the way he uses the Greek words, not the English translations. If John consistently uses the same word in the exact same way throughout his Gospel, and the only differing use is in the middle of the 10th chapter where he uses a plural form and cites a Psalm prophecy where we are all gods, then it is evident we should assume John is clearly using the Greek word in the same Greek way everywhere else, including John 1:1, unless we have evidence to differ from the norm. This is evidence, we will see, you have not adduced. As for my firebreak;

By “divine”, I mean Jesus was divine in origin; he was the son of God. This placed him in a unique relation to God. Additionally, he was given unique authority, unique titles, a unique role, and God worked through him uniquely, specifically because he was the son of God, and therefore God’s representative on earth. He was a human of divine origin, who was appointed as the unique agent of God.

This is still a little vague for me. Saying he was the “son of God” (lower case!!) is rather vague since we’re also all sons of God in the Bible. So, answer these questions: 1) Does Jesus pre-exist His birth? 2) Is Jesus destined to eternally rule the kingdom of God? 3) Is Jesus the Creator alongside the Father? 4) Are Jesus and God of the same ‘subtance’? This term might carry baggage but I trust you know what I’m talking about. 5) Is Jesus to be worshipped? 6) How did the Word exactly become Jesus during the incarnation? What sense at all does it to make to posit a discontinuity between the Word and Jesus when the incarnation took place? Did the Word suddenly cease to exist and Jesus appeared in place of the Word?

This will give me a much better grasp on your thoughts. Your answer to 6) will be crucially important to my next response. As for the Synoptics;

… numerous commentators who read it as “God”, do so as an interpretive decision based on their interpretation of other verses first (as they state explicitly). Even though they don’t believe the Synoptic gospels present Jesus as God, they interpret some passages of John’s gospel as presenting Jesus as God, and therefore conclude that the logos is being called God in John 1:1. This is an interpretive conclusion based on what they believe John’s theology to be.

I agree that scholars traditionally have viewed the Synoptics to contain a generally lower Christology, but this is clearly changing, and quickly, in recent years. Not to mention the book I have been constantly mentioning in this conversation, Richard B. Hays Figural Christology and the Fourfold Gospel Witness (BUP 2014). This is a major study which shows that each Synoptic author, through his use of the Old Testament, understood Jesus to be the embodiment of Israel’s God. Taking a look at the back cover also reveals exactly who has endorsed this book (and thus agrees with it): N.T. Wright, Richard Bauckham, Joel B. Green. These are impressive scholars. In Bart Ehrman’s 2014 book as well, it is revealed Ehrman also concedes the Synoptics think of Jesus as God in some verses. In Bart Ehrman’s debate with Justin Bass, as they were debating if Jesus historically claimed to be God, Ehrman was confronted with Matthew 11:27/Luke 10:22, and he did not debate these verses at all, in fact he just said he thought they were ahistorical. Andrew Loke’s monograph The Origin of Divine Christology (Cambridge University Press 2017) not only argues Jesus is God throughout the New Testament, but that Jesus historically claimed to be God. To my knowledge, this is the first monograph in some time to directly argue this. Continuously, I will also point you to the most recent issue of Cambridge’s journal New Testament Studies, Jason Staples paper ‘Lord, Lord’: Jesus as YHWH in Matthew and Luke (2018). I will quote the abstract:

Despite numerous studies of the word κύριος (‘Lord’) in the New Testament, the significance of the double form κύριε κύριε occurring in Matthew and Luke has been overlooked, with most assuming the doubling merely communicates heightened emotion or special reverence. By contrast, this article argues that whereas a single κύριος might be ambiguous, the double κύριος formula outside the Gospels always serves as a distinctive way to represent the Tetragrammaton and that its use in Matthew and Luke is therefore best understood as a way to represent Jesus as applying the name of the God of Israel to himself.

I suggest you read the full study, it’s an excellent paper. I know through email correspondence, as I have mentioned earlier, that Staples thinks it is plausible that Jesus did in fact say ‘Lord Lord’ about himself (perhaps not in the exact ways depicted in the Synoptics) since the passages it appears in are at the heart of Jesus’ message. Nevertheless, this further argues for an increased recognition of Christology in the Synoptics (particularly Luke and Matthew where the Lord Lord passages appear). It’s clear that in the more recent literature, support for a higher Christology everywhere, including in the Synoptics, is surging. I find this in part to be caused by the recent emergence of an early high christology as the earliest christology developing almost immediately after Jesus’ crucifixion. The evidence is piling up and, quite frankly, you have a lot of explaining to do Jonathan!

Finally, you have an extended discussion and quote a number of scholars on theos and whatnot. There is no doubt you have found almost every person to ever argue for the divine translation, but of course we must once again reacknowledge that in the great majority opinion of Greek scholars, the translation God is not only preferrable, but it is so much more preferrable given the context that the only time divine is even mentioned in a footnote is in the NET, where it is actually rebuked as a translation. You have not addressed the contextual considerations I mentioned, which I will re-post:

- The Word exists in the beginning. “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with theos, and the Word was theos”. John 1:2 even says “He was in the beginning with God.”

- In John 1:3, we’re told “All things came into being through him, and without him not one thing came into being.” This is talking about the Word, the entire Johannine Prologue is talking about the Word (who is in fact Jesus, not only Jesus after the incarnation). According to John 1:3, EVERYTHING that came into being was through the Word, and if it were not for the Word, then nothing would have come into being.

- In John 1:14, we are told the Word is the “father’s only son”. It’s clear that the Word possesses a relationship with God the Father that, not only does not exist with any other being to the Father, but cannot exist with any other being to the Father.

You have not addressed these contextual considerations. When I pointed out that scholars (and I’ve quoted C.H. Dodd earlier, and I can quote others) also recognize ‘a god’ as a perfectly valid Greek translation, you mentioned that this translation would make it appear that there were more then one God. Exactly my point, that is precisely a contextual, not grammatical consideration you have made. And so the same needs to be applied to divine, is it contextually sound? In the great majority of scholarly opinion … no. Not a single authority you cited says that divine is a grammatically superior, because it simply isn’t. There are three perfectly valid translations at hand. Even Charles Iron only seems to prefer divine because he thinks it would be ‘modalism’ otherwise, which quite frankly isn’t true. You provide a citation to Keener that actually seems to flat-out contradict you:

"The Old Testament had personified Wisdom (Prov 8), and ancient Judaism eventually identified personified Wisdom, the Word and the Law (the Torah). By calling Jesus “the Word,” John calls him the embodiment of all God’s revelation in the Scriptures and thus declares that only those who accept Jesus honor the law fully (1:17). Jewish people considered Wisdom/Word divine yet distinct from God the Father, so it was the closest available term John had to describe Jesus.

Keener directly says John called Jesus “the Word” here. So doesn’t this quotation support me? You use it to show that Wisdom is distinct from the Father, which I agree with, just as the Word is distinct from God. You also quote another authority that sounds to confirm my claim, Köstenberger:

"The term “the Word” conveys the notion of divine self-expression or speech (cf. Ps. 19:1–4). The Genesis creation account provides ample testimony to the effectiveness of God’s word: he speaks, and things come into being (Gen. 1:3, 9; cf. 1:11, 15, 24, 29–30). Both psalmists and prophets portray God’s word in close-to-personified terms (Ps. 33:6; 107:20; 147:15, 18; Isa. 55:10–11), but only John claims that this word has appeared in space-time history as an actual person, Jesus Christ (1:14, 17).

So Kostenberger clearly says that according to John, the Word from the prologue is Jesus. Again, I agree with this. That’s exactly my point, Jesus is the Word, not just the “Word incarnated” (this quote in fact contradicts this claim of yours), which is the clear reading of the text and supported by scholarship.

I do not know which quotation you provide that I am supposed to rebut. They all seem to be on my side, or at least they say nothing so far that I see as contradictory to what I’ve said. I also think you made another mistake regarding my position. You point out that out of 83 uses of theos, only 2 cannot refer to the Father. When did I say theos was not the Father in John 1:1? Again, my ‘interpretation translation’ would go like this:

John 1:1: In the beginning was Jesus (logos), and Jesus (logos) was with the God the Father (theos), and Jesus (logos) was the God the Father (theos).

In interpretation terms, Jesus is both with God at the beginning and is God. Same being, different persons. Basic Trinitarian (or even Binitarian) stuff. And you seem very quick to pounce on the consistency of theos when it means the Father … but doesn’t that contradict your own claim that theos in John 1:1 should be translated as divine? As in, you don’t think theos should mean the Father in John 1:1? Can you clarify this?

That concludes this response.

NOTE: To update just one point, I read the review of Boyarin’s The Jewish Gospels and it appears as if the author has simply made a mistake. Boyarin says he’s arguing for binitarianism, and the blog author quotes him on this, and then proceeds to interpret this as ditheism (two gods). I’m dead sure this is not what Boyarin is talking about, binitarianism is just trinitarianism except three persons instead of two. I think this author is not an academic. NOTE 2: Reading his ‘About Me’ page confirms he is not an academic. I will post a comment under his blog.

This is pretty breathtaking. All this time I thought you were a Trinnitarian, but now you’ve given a strict Modalist interpretation of John 1:1.

This is seriously your “interpretation translation”? You believe Jesus is “God the Father”?

I have explained this repeatedly. I believe the first theos in John 1:1 is God (the father), and the second theos in John 1:1 is an adjectival form of theos meaning “divine”. Remember, the “consistency of theos” argument is yours, not mine. I don’t agree with it.

This is pretty breathtaking. All this time I thought you were a Trinnitarian, but now you’ve given a strict Modalist interpretation of John 1:1.

Oh come on now, Jonathan! For some reason I find this funny.

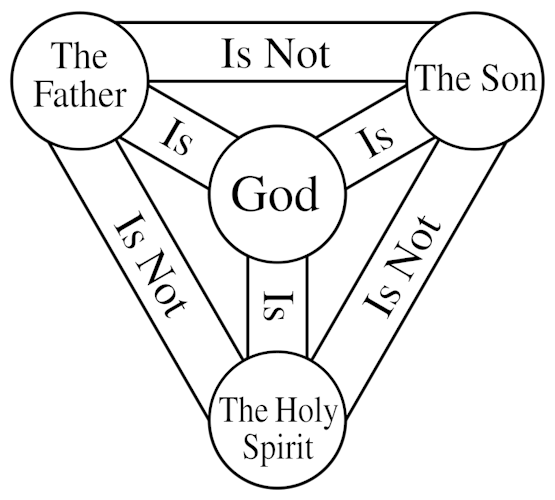

Trinitarianism says that God is one being and three persons. So necessarily, all three persons are one being with each other. The Holy Spirit is the same being as the Father. The Holy Spirit is the same being as the Jesus. Jesus is the same being as the Holy Spirit. This is Trinitarianism, not heretical Modalism. Exhibit A:

See? That’s not Modalistic. If you were not making a consistency argument I don’t know why you were stressing that theos is used 83 times and only 2 times do not definitively refer to the Father. Anyhow I await your full response. Or perhaps I have converted you to orthodoxy!

Please read the Scutum Fidei. It says explicitly that the Son is not the Father. You have just written that the son is the Father.

I already told you explicitly, the purpose was to show that your “consistency argument” results in a nonsensical result.

Oh you’re not going to respond to the rest of my post?