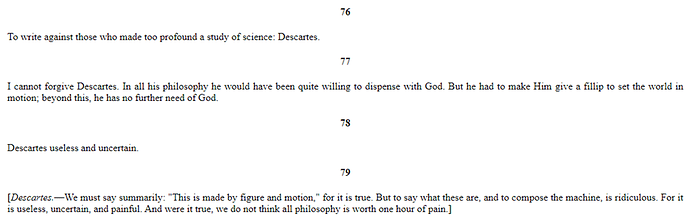

To write against those who made too profound a study of science: Descartes.

I believe Pascal has in mind his own idea that truth is known in more ways than reason alone, which is reflected in this note:

The heart has its reasons, which reason does not know. We feel it in a thousand things. I say that the heart naturally loves the Universal Being, and also itself naturally, according as it gives itself to them; and it hardens itself against one or the other at its will. You have rejected the one, and kept the other. Is it by reason that you love yourself?

On the next note about Descartes,

I cannot forgive Descartes. In all his philosophy he would have been quite willing to dispense with God. But he had to make Him give a fillip to set the world in motion; beyond this, he has no further need of God.

Pascal knew Descartes personally. The rest is a description of Deism. Finally,

[Descartes. —We must say summarily: “This is made by figure and motion,” for it is true. But to say what these are, and to compose the machine, is ridiculous. For it is useless, uncertain, and painful. And were it true, we do not think all philosophy is worth one hour of pain.]

I believe the first sentence refers to an unbroken chain of natural causes-effects back to a first cause. “The machine” refers to the universe operating like a machine. I’m not certain whether Determinism was a “thing” yet, but that’s what it brings to mind for me. Once the first domino is tipped, everything else happens by necessity. Free will is an illusion, etc. Such a conclusion is useless, uncertain, and painful to us, according to Pascal. Regarding the last line, Kierkegaard was famously critical of philosophy, but no particular quote jumps into mind. (Memory failure?) I love this quote from Wittgenstein’s journals, though:

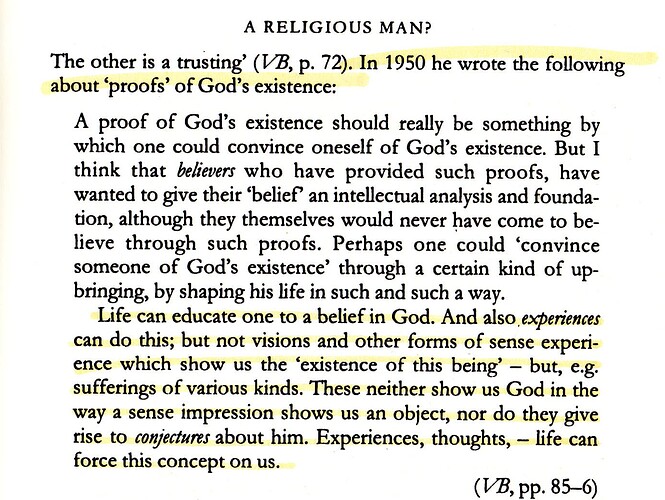

Is what I’m doing really worth the labour? Surely only if it receives a light from above. … If the light from above is not there, then I cannot be any more than clever.

Addendum: Dang! Forgot his famous quote on philosophy: “Philosophy is a battle against the bewitchment of our intelligence by means of language.”

And his thoughts on proofs of God’s existence: