- Quick Youtube trips into Epicurus’ philosophy:

Thank you, @Terry_Sampson

Those should be helpful to other participants as well.

After I had posted the above, I did listen to the entry in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, which @jay313 had mentioned. It was helpful.

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/epicurus/

I’ll listen to the video you shared, too.

Sorry I’ve fallen behind. I’ll catch up tomorrow (fingers crossed) with a combined post on lectures 2&3. My preliminary thoughts are along these lines:

So the main point of the whole series: Jesus and the gospels. Does God intervene in the world or not? The obvious problem is discerning when God has intervened or when God has not. I’ll skip over the intricacies of that question, which I’ve touched on elsewhere, and focus on the “quest for the historical Jesus” (a misnomer, as Wright says).

Copying my comment for lecture 3 from above

Finishing lecture 3, I cannot resist poking a bit at one of Wright’s comparisons. It doesn’t detract from is larger message because He is more careful later in the lecture.

He says we know the Romans destroyed the second temple as surely as we know water is hydrogen plus oxygen. And from this you may take the message that history is as certain as the physical sciences. The problem is that the our knowledge in the physical science is a great more detailed in precise quantities. And in fact his comparison is case in point. We know a great deal more than Wright’s vague description of water as hydrogen plus oxygen. We know water is composed of units combining two hydrogen atoms and one oxygen atom. With history we only know what people bothered to describe in writing. So considerable detail is lacking and will never be known.

But… later on, Wright takes pains to describe history as seeking stable footing on shifting sands. Nobody describes the physical sciences in that way. LOL

I was reading the account of the event by Josephus this morning.

So there are more details available in this case than many other historical events. So you could object that the physical science including that of water is more simple even when you include such details as reaction rates under various conditions such as temperature and pressure.

Ok. Ok. Ok, Mitchell. Wright’s comparison is not perfect. You’re right.

I think the shifting sands he refers to are not history itself or the serious study of it, but the various methods of historical (or “historical”) study he is critiquing.

This bit starts about 46:43:

Henry Chadwick admitted if theology is true to itself it can’t simply snatch a few biblical texts to decorate an argument constructed elsewhere. It must grow out of historical exegesis of the text itself.

I understand the resistance many theologians perhaps some of you experienced undergraduate biblical studies as the lifeless rehearsing of Greek roots and reconstructed sources that too was a way of avoiding history, of pretending that digging the soil was the same thing as growing vegetables. When done properly historical exegesis […] ought to be producing the plants themselves […] and letting them bear their own fruit […]. But it will only do this if it’s allowed to be itself, if history can get on with its work without people looking over its shoulder and warning it about the shifting sands or telling it it’s much safer to play the violin without the bow That would take us back to the Petrine temptations again so I plead to the theologians don’t reject history you have nothing to lose but your Platonism.

[Transcript cleaned up a bit by Kendel]

Thanks for copying your earlier post. And then replying.

What do you think of Wright’s description of how one ought to study history and the value of its inclusion in [edit: natural] theology?

Well, I think “Jesus and the gospels” is the start of what he is saying. Something more like this: Jesus and the gospels as part of history and nature are essential components of anything that might call itself “natural theology.”

As a scientist, it was interesting to hear Wright’s description for the methodology of doing history and compare it with the scientific method.

Wright said the historical method involves “abduction” which I looked up in the Standford encyclopedia…it means “inference to the best explanation”. Wright said the methodology of doing (good) history involves constructing hypotheses and then trying to verify (or refute them) by careful study of the data…which in history would be things like old manuscripts or archeology. He admitted that no historian is totally “neutral” (everyone has a worldview that influences how one sees the data), but that one can minimize imposing our ideas onto history (minimize the eisegesis that he is accusing the German theologians wrapped up in apocalypse thinking of) by careful study of the worldviews and motivations of others–by studying the culture of the historical author and his audience. In this way, “historical science” proceeded as a back-and-forth between proposing hypotheses, and testing them, and hopefully that method gradually iterated towards the “truth”, much as science is seen to do.

I assume Wright will argue in the future lectures that he is a rigorous historian–one who has studied first century Jewish culture and thought, and therefore his ideas of a “Historical Jesus” are more accurate than those of enlightment philosophers or German historical-critics who apparently have not done their homework to research original Jewish texts, or contexts.

At the very end, someone in the audience posed an interesting question saying “In science, hypotheses are falsifiable and there is a “killer experiment” that could be designed to refute the hypothesis but that seems not to be the case for history”. Wright responded that there was “killer evidence” possible in history also…for example archeologists could uncover artifacts or information that would refute a historical idea. However, Wright added that history was “fuzzier” than science because historians often had to simply wait around for such new archeological evidence to be exposed before certain ideas could be rigorously tested. In contrast, in science one can design experiments which can quickly test hypotheses “in present time”.

I watched lecture 3.

I liked Dr. Wright’s explanation of the meanings of the term “history”. I know he will be teaching the importance of understanding the historical context of Jesus, to understand the depth of Jesus’ teaching. I agree that that is very important.

I know that Dr. Wright has been respectfully critical of C.S. Lewis for neglecting to place Jesus in His historical context. See

One thing that I’ve been thinking more about in recent years is that every culture creates narratives about themselves, often with the motivation to make themselves look good. I think Western peoples are coming to terms with the “colonialism” narrative. It’s painful, but I think it can be a healing process. Here in Canada, we have various narratives about ourselves that came out in the history I learned in school. Since school, I’ve read a fair amount of history, but I will admit that a lot of it was written by historians from the English-speaking Western nations. I am making an effort to read history/stories written by Indigenous peoples, and non-English peoples (translated).

I think I am learning that the discipline of the historian is very demanding. The historian must get facts straight, and they must interpret history in a balanced way, recognizing differing viewpoints. They may make conjectures about the meaning of history, but this must be done carefully, stating the assumptions under which the conclusions are drawn.

Theology? Of course! Natural theology? Not so sure about that. And I hardly think it provides objective evidence for religion. This doesn’t bother me because dealing with the subjective nature of life looks like the whole point of religion to me. But it is even more foolish to ignore history and the subjective necessities of life.

I like his focus on Epicureanism because it really is the greatest and oldest challenge to religion.

Yeah. Sorry I left out “natural” before “theology.” Good call. I went back and edited my post and marked it as an edit.

Your point about the subjective nature of life is interesting.

What do you mean by the “subjective necessities of life?”

It is part of a contrast with science which is all about objective observation. Life is subjective participation. Science is about procedures which give you the same result no matter what you want or believe, but that is not something you can live your life without. Living your life, what you want matters and is even central. To be sure religion advises that not all desires are equally fulfilling. But even when it is love and serving others, that is not something you are pursuing like a machine. If you are not serving others because you want to, then your service is rather hollow.

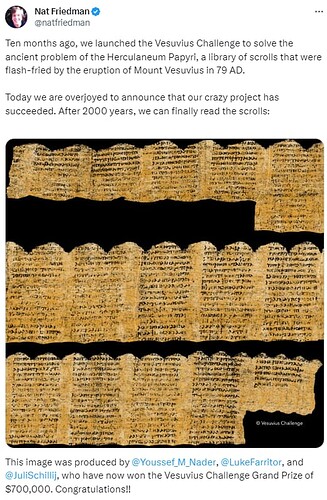

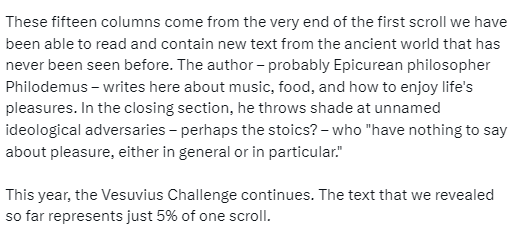

Yes, I was just copy-pasting my notes. Resuming now, but I thought you would find this interesting. A library of scrolls burned in the Vesuvius eruption was just decoded. The first bits are from an Epicurean philosopher!

One of the videos that @Terry_Sampson shared mentioned this fire and the destruction of Epicurus’s writings. That anything at all remains from the library fire 2 thousand years ago is astonishing. Crazy project indeed!

Assuming Epicurus was wrong, librarians over time and geography weep tears of elation over this wonder!

I don’t think this particular library contains anything by Epicurus. He died 300 years before Vesuvius blew. Philodemus may have some “quotes” from him, though. Who knows?

Karen, I’m glad you picked this topic up.

Your last point about the “present time” jarred something loose in my mind.

I think in one lecture or another, Wright does mention the impossibility of people today really “going back” to thinking as 1st century Christians, Second Temple Jews or anyone in the OT. And this is worth working through a bit I think, particularly in light of Wright’s proposal of a Hermeneutic of Love.

Even with the best possible information about the time, and the best possible grasp on how people thought, what the references meant to them, and all the rest, we know things they didn’t know, understand things differently than they did, and we process our world differently because of it.

While I think we can have a very good grasp of how and why 2nd Temple Jews read and understood the prophets and the law, we won’t actually think that way ourselves. Even though we can talk about how they did.

I am sure Wright is aware of this and accounts for it. (It’s been a while since I listened to the rest of the lectures.) I think it’s something that we as listeners need to keep in mind. The best we can do is rather like the SCA does. We can inform ourselves as much as possible, consider what that means, try thinking a bit in that mode, but it can never, really be ours again. We bring to much to it for our attempts to be more than short-term attempts.

I don’t know to what degree the things I mentioned here will be of importance, if at all. But I think there is always a person, who thinks they can really “get back to that time,” if they try hard enough, but they don’t recognize that the thing they are doing is only a flawed simulation.

“Hermeneutic of Love”

I googled it this morning, expecting to find something by or about NT Wright’s practice as a historian and theologian. No. Much more. I should have looked it up a month ago:

Even Gadamer! Wednesdays with Wright: A Hermeneutic of Love – the archives near Emmaus

Revelation and the Hermeneutics of Love | SpringerLink.

This piece by Wright reviews not only this hermeutical idea but gives a nice overview of major themes in the lectures.

Well, yesterday I hoped to pull some ideas together from my notes on III, only to realize they were on IV. Good grief. Will try to have something more up tomorrow.

I did find Wright’s point regarding the significance of Jesus in understanding hiin the introduction attention-grabbing:

All history must refer AND defer to him.

This is the abstract of Augustine’s concept of a hermeneutic of love as described in a blog post above.

Large sections of what he said sounded very much like criticisms I remember. That’s a bit shocking; if criticising historical criticism is still useful that implies that people are still doing it and falling into the same dead ends as my professors noted clear back in grad school!

I loved his note that the British chop off the parts of German scholarship they don’t understand and use what is left to answer their own questions; also the point that historical criticism ended up with little history and lots of criticism.

I agree, That was something that annoyed me in grad school; to a large extent it was possible to make Old Testament passages mean most anything by just shifting what historical-cutural aspects you wanted to emphasize.

I had professors who regarded analyzing the grammar to be the primary point of interpretation, an approach that leaves Xenophon flapping in the wind; then there were those who went to the other extreme – I think at times in reading Augustine’s City of God we spent more time looking at the historical background than reading the text.

I agree here as well.

Observing situations where learned members of a panel get into arguing nuances of a ancient worldview came to mind here.

We once had as a guest speaker an archaeologist who specialized in “ruins hunting”, i.e. examining questions historian had, making guesses as to what sort of thing might answer those, making more guesses as to where such might be found, then hunting for possible ruins to match the guesses. She noted that she irritated colleagues because she had a penchant for digging at “random” hills; they joked she thought the ancient near east only has hills because of ruins.

That’s one reason that discovering the big Ugaritic library at Ras Shamra was a big deal; here was a whole new source for a different perspecitve on the region’s history.

Well, a means for reading them was proven, anyway.

The patience involved is immense. First the scroll has to be scanned to build a model of the layers, which were deformed by both heat and the weight of ash. Next scans have to be done following those contours while giving output to a flat surface. Finally they scan for chemicals used in ink, or rather their derivatives since the heat that turned the scrolls to charcoal altered them. I really admire the university student who was the first to actually read just one word – after that it became just a matter of fine-tuning the process.

Something I haven’t read but assume is involved is scanning the scroll with it laying on different sidesto get the best image of the layers, and then again for each successive scan. To read just one line would require rotating the scroll possibly all the way around.

It was the eruption of Vesuvius. Had it been a fire, the scrolls wouldn’t have been carbonized; that required intense heat with negligible oxygen.

This is one reason that some doctoral dissertations in ancient near eastern studies can be so narrowly focused; they can’t just devote themselves to studying the thing they’re interested in, they have to immerse themselves in everything available for at least a century before their focus plus everything within common trade distances of their location. I can’t remember where it was, but there was a discovery while one of my professors had been nearly finished with his doctoral thesis that fell within a hundred kilometers of a site he was examining; he said he was both thrilled and depressed: thrilled because it meant a lot of new information, but deprressed because all that new information meant he was going to have to start over.