Your point is fair, @wetlandsguy, but applicable only if I actually assumed that. I’m not. All biblical authors had agendas of one sort or another, and wrote in and into various contexts. To acknowledge this, however, is not IMO equivalent to assuming (as I believe many contemporary scholars do) that we today are in a better position now to determine what Jesus actually said, than authors much closer to his own time. Whoever they actually were, I think we can assume that they had access to more sources, both written and oral, than we have today. It’s not as though modern scholars have found non-canonical earlier accounts than the gospels are commonly taken to be, accounts that might be used to pull rank on them. So, I remain astonished at the chutzpah of the Jesus seminar.

Wow thank you this is very illuminating

well if we’re talking about agendas, it sounds like you’re promoting an atheist one, which I think in itself can be biased: I think the existence of God is something that can wholly never really be disproven, because in his depiction, he is an all-powerful being whose power is beyond our comprehension

I can’t argue with that. Your astonishment is yours. Setting aside the Jesus Seminar, however, as they are not the only ones challenging the modern evangelical literalist viewpoint, I would still challenge your premise, although it is a bit unclear.

So, let me state what I think it is: the gospels and writings of Paul that presume to provide actual words of Jesus because of the proximity to the event are more reliable as being the actual words of Jesus than what modern scholars could determine today. Is that fair?

What if it was determined that the actual authors wrote over a period of many generations each one adding his own viewpoint (which is demonstrated in conflicting narratives) and which resulted in a developing, or dare I say, evolutionary framework that actually took hundreds of years (through the canonization process) to produce a cohesive NT theology?

Would that have any bearing on your premise?

Why don’t you repost this in a more appropriate thread? We were just discussing this question over here:

I have not spoken to the existence of God at all. I am not in the business of promotion, but of truth-seeking. Your original question was about how to interpret the Bible.

You set up a dichotomy: certain things are not true in the Bible that you thought should be true. That raised questions for you. The biggest one being - what am I to make of this? That set you off to ask others how to reconcile this.

My answer is understand what it is you are reading. If the answers to those kind of questions lead you to disbelieve in God, you have to ask yourself what kind of evidence (type, quality, form) you will accept in order to believe.

Perhaps restating it this way is helpful: I will only believe in God if I find out the Bible is a literal historical book (collection of books - and which ones, by the way) that I can independently confirm as being reliable.

If so, perhaps there is no God, or perhaps you have set up an unrealistic expectation of what the Bible is.

Thanks. I am not trying to derail this thread, but instead trying to get at the heart of the poster’s dilemma. He/She is conflicted because of finding out stuff in the Bible isn’t historically accurate - so how to make sense of it.

I agree with him/her. It’s a problem. So how do you reconcile it?

I say try to understand the text for what it is and look at how it was created and for whom it was created and for what ultimate purpose.

Different people reconcile it different ways, depending upon their theological commitments.

I agree with what @TedDavis said above. More broadly, the question is whether the gospels (not Paul’s letters) contain Jesus’ ipsissima verba (precise words) or ipsissima vox (precise voice). I vote for the latter. Daniel Wallace’s definition of ipsissima vox is that “the concepts go back to Jesus, but the words do not — at least, not exactly as recorded.”

Edited addition that I forgot the first time:

That’s pretty standard procedure for all biblical interpreters.

Why does it have to be binary? I’ll answer for you: because of presumptions you impose on the texts.

I believe that is the exact problem we encountered with evolution and Genesis. If you box yourself in with self-imposed constraints, you are limited in your ability to look at all possibilities. In fact, more plausible possibilities.

You presume too much, my friend.

Again, I haven’t described my position, so you presume too much.

Hundreds of years to write the gospels, or hundreds of years to write Paul’s letters? You keep conflating various documents as if they were one. And you conflate the development of theology and the development of the “Jesus tradition” (e.g. 1 Cor. 15:1-8) and the various manuscripts of the NT. Climb down off that soapbox for a while.

Yes, that’s fair. As far as I can tell, @wetlandsguy, we differ on this b/c I am approaching the issue as an historian, not a biblical scholar. Certainly I lack some of the tools of the biblical scholar, but historians do similar things when we analyze texts written long before our own time. Yes, we hypothesize about which source(s) are the most reliable, and for various reasons, but in general we aren’t going to conclude that a source written 120 or 180 years after purported events is a more reliable account of what someone actually said, than an account written within a generation or two of that person.

This doesn’t mean that we just ignore authorial agendas; show me the historian who does this, and I’ll show you a bad historian. Nor does it mean that we simply accept at face value what the earliest sources say. But, it does mean that the best sources for what someone actually said were written (if not by that person herself) by people who knew that person well, or else by people writing about that person who were (in turn) relying on people who knew that person well, or … take it back further if you wish. You don’t just get to say today that an historical person did say this and did not say that, based just on one’s own biases and viewpoints and hypotheses today. Historical actors are complex; they said many things, sometimes contradictory things, and we don’t have the right as historians to insert ourselves into the picture to settle the matter arbitrarily, as if we were actually there ourselves. What we can do, is to find as many early sources as we can–or later sources that directly refer to alternative early sources, now lost–and construct our accounts of an event on that basis.

I find lack of clarity in your phrase, “the modern evangelical literalist viewpoint.” Quite possibly, this is recognized terminology that I don’t recognize–in which case, please offer a working definition with an example or two. Here you’re implicitly associating me with a particular viewpoint that I cannot define more specifically, so perhaps it’s not applicable to me.

I’m modern, and (if one is not asking the question with politics in mind) I often identify as an “evangelical,” but usually I avoid the word “literalist,” though certainly I take “literally” many biblical statements, depending on their context. However, many people criticize me for being too “liberal,” not “literal,” when I interpret a given text.

In my experience as an historian (with significant training in physics in a previous life), it can be deucedly difficult entirely to avoid hemming oneself in with artificial constraints–in perhaps every area of science and scholarship. Obviously I am no exception myself, but neither are those biblical scholars who simply assume/believe/take it for granted that all “gods” are human constructions. Absolutely, we should be very suspicious of claims involving the “supernatural,” but we must not just presuppose that such claims simply could not be true. A proper methodological naturalism in science, e.g., does its best to construct an account of how something happened on the basis of known natural properties and powers, not on speculations about powers “above nature.” However, that is not an entirely objective exercise, as persuasive as it might be to many. Assumptions, rather than proven facts, are deeply embedded within it. Sometimes, it may be appropriate to ask a biblical scholar to engage in a willing suspension of unbelief, to turn William James on his head…

I am not trying to be argumentative. I was trying to read between the lines of where you stand based upon a few things you said. I am simply appealing to a more open mind since you leveled a charge against a group without (in my view) an adequate defense of your position against an honest review of theirs.

I will however give you a hint at what I am leading up to which is that I believe that taking the NT as authoritative as “the Word of God” on the basis of the texts saying so in the absence of a demonstration of why it is so, is not questioning faith or belief in God. The same can be said of the OT.

Again, I am referring back to the original problem presented in this thread. I have attempted to explain it.

Now it’s your turn.

@wetlandsguy, quick clarifying question. When you say, “…taking the NT as authoritative, as ‘the Word of God’ on the basis of the texts saying so…”, to what texts are you referring? What texts claim the NT to be authoritative and/or the Word of God?

II Peter 3:16 uses the phrase “other scripture” when speaking of the letters of Paul. So, the inference at least is that some of the authors may have believed they were completing the OT.

II Peter is of course pseudopigraphical with a wide span of when it was written. .

Nonetheless, many people including myself (formerly) would have argued that the NT (27 books) is authoritative on this basis as well as the description given in II Timothy 3:16.

Kinship analysis of the king lists of Genesis 4, 5. 10, 11, 25 and 36 indicates that the rulers named were historical persons and their marriage and ascendancy pattern is authentic.The pattern could not have been written back into the texts at a latter time. This kinship pattern, involving two wives and endogamy, has been identified with Abraham and his Horite Hebrew ruler-priest caste.

What is kinship analysis?

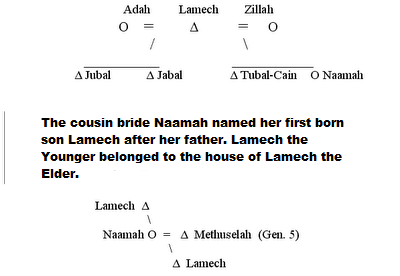

Kinship analysis is a tool of cultural anthropologists whereby they can diagram how people are related and then use the diagram to do an analysis of the kinship pattern. Here is an example. This shows that the lines of Cain (Gen. 4) and Seth (Gen. 5) intermarried. Naamah married her patrilineal cousin Methuselah and named their first born son Lamech, after her father. This is an example of the cousin bride’s naming prerogative.

Thanks @Alice_Linsley, that’s interesting. Do you have some academic work demonstrating more of this type of work? I had never heard of this method before just now. I just started looking up ‘kinship analysis anthropology bible’ or something like that and came across this paper which seemed like a good place to start to get a hang of how it is used by anthropologists, especially given the number of citations and what I guessed this field might get (send me a PM and I can send the PDF for anyone interested):

Kinship Structures and the Genesis Genealogies

They do seem to generally agree with you that “there is remarkable unity of relational principle behind the particular kinship statements of various sources in Genesis” but don’t take that to be evidence of any historicity. About the historical nature of the accounts they say:

The historical continuity of the persons depicted are of limited importance, and even the genealogical links drawn laterally (such as that between Israel’s “sons”) are important only in that they serve as culturally specific backdrop against which particular lines and individuals are stressed.

I’m not sure what kind of consensus exists in the field but it is really interesting none-the-less. If you have other sources to include here that’d be great.