Not if the change was made before the earliest manuscript that is known. You seem to ignore that fact the scribes felt free to make changes when they were copying and even if it was only a few decades before the text was “frozen” so to speak that still leaves plenty of time for changes to be made.

There is counter-evidence in spades so long as one interprets all the open-ended, non-conclusive, hypothetical data in a way consistent with my theory."

I do sincerely appreciate the honesty by which you noted the less-than-certain nature of these spades of counter-evidence. But that goes directly to my main point. All these counter-evidences (excepting dependence on Mark) are hypotheses, interpretations, or speculations. Even critical scholars that have no theological commitment I’ve read have no consensus on many of the above points.

I’d heard many of the arguments above before, but one new one (it is perhaps vaguely familiar now I think about it) that is simply dumbfounding to me…

I utterly reject this claim as ridiculous when it is made to argue for a second century date for the Pastorals… but it seems even more absurd applied to Acts. Acts describes the nascent early development of the church’s ecclesiology for goodness sakes. How is it supposed to reflect a second century church exactly?

They didn’t have deacons; hence the chaos in the church, and so Acts describes the initial challenge caused by the lack of such deacons, and the way the church came up with the initial idea of having deacons in the first place.

The churches across the empire didn’t have established elders or leadership, hence why one of Paul’s main missions during the journeys recorded in Acts is to establish Elders for these nascent churches.

They didn’t have a developed ecclesiology on how to handle Gentiles entering the church and had to have a full counsel to work that out… this fits better in the 2nd century?

You’ll have to detail for me a bit more exactly how this argument goes that Acts has an ecclesiology closer to 2nd century church? This honestly strikes me as absurd at its face, but I really would be open to hearing the argument itself.

Not really true. It mostly just takes one of them to be correct for Luke to have written Acts well after Paul’s death. They do not all need to be correct. If one is correct Acts was written later.

They are arguments flushed out in scholarly journals and books. There is disagreement on almost every issue in NT studies. So yes, not all scholars will agree with them.

Your claim that Acts should narrate Paul’s death is also a “hypothesis, interpretation or speculation.” Your argument is granted no authority of position here. Each position must be carefully argued and justified.

Correct. That Luke used Mark is the primary one that is a consensus position. The next closest is that Luke’s narrative shows knowledge of the temple’s destruction. Many of the others are more controversial. But my point was there are plenty of potential reasons for dating Luke-Acts late.

Here I can only reflect you to Richard Pervo’s Daying Acts. My copy is on the way. I’m reading a very recent book by Armstrong now that argues for the 60s, when the book comes in I’ll cite some stuff. It might be my last two bullet points go together. But here is a quote from a scholar on Reddit that may give the gist of a type of argument along these lines:

Vinnie, I like it that you give sufficient details to estimate how reliable some claim is. This does not mean that I agree with all claims.

As a reminder, I wrote that I do not know when Mark was written but think that pre-70 is more likely than post-70. If the version we know was written post-70, it would not shake my world at all.

About taxation: there were many taxes but the most relevant ones in the context were tributum capitalis and tributum solis. Of these two, the one more likely to be paid in coins intended to the empire was tributum capitalis. The tributum capitalis was a regular poll-tax instituted on provinces by the Romans during the Imperial period which was paid in coin directly to the Romans. The start of the tributum capitalis taxation in the area is not known but documents from Egypt show that it was in use 33/34 CE and possibly decades before that.

About denarii: the Temple area in Jerusalem was a cosmopolitan area in the sense that it attracted Jewish believers from all parts of the known world. It is very likely that there were coins from several areas in circulation, although many just in small numbers. When Jesus asked to see a denarius, he did not ask a coin but a specific type of coin, the Roman one. This pericope does not reveal how common denarii were, it only shows that there were denarii in the area. A Roman coin was a logical choice because the question was about the taxes paid to Romans. Denarii were probably not used for payments in the matters of the Temple. I have understood that one reason for having money changers in the Temple area was because all coins were not accepted in the matters of the Temple.

I do not know which timing is correct but there are valid reasons to support both a pre-70 and a post-70 interpretation. We do not know when Mark was written so we have only educated guesses.

It is good to realize that our opinions in this matter are not objective. We look at the details through our personal worldview, mainly formed by the education we have received. If our teachers have supported a particular hypothesis, it is likely that we will give more weight to details that can be interpreted in a way that supports the interpretation our teachers liked. Unfortunately, the level of education does not remove this partiality - professors are as likely to make errors than the other teachers. There is even a study suggesting that the quality of the manuscripts written by professors is worse than those written by other academic teachers - university professors are simply too busy to allocate as much time for research and writing of manuscripts and the lack of thinking time becomes evident in the output. So, it does not matter whether our teachers were parents, workers in a church or academic staff, we all suffer from the lack of objectivity. It demands conscious effort to reach a higher level of objectivity in these matters.

Its irrelevant when the autgraphs in question were put to print (so to speak).

Reasons why:

-

Matthew, Mark and John were all disciples of Jesus.

-

The gospel writers (with the exception of Luke) wrote what they witnessed.

Luke was a physician and possibly a Gentile. He was not one of the original 12 Apostles but may have been one of the 70 disciples appointed by Jesus (Luke 10). He also may have accompanied St. Paul on his missionary journeys.Saint Luke | Biography, Feast Day, Patron Saint Of, Facts, & History | Britannica

In his writings, Luke plainly tells us that he is collating from other sources, many of whom who were eyewitnesses. The point is, Luke was not an eyewitness, therefore, it doesnt matter what date his books were written.

For me these kinds of discussions focus so much on trying to find error, they become a stumbling block and people get themselves confused and doubt begins to creep in.,

Of course, the text never says who wrote them, except there are indications in John. Matthew is interesting, as the first two chapters have elements that would have had to come from Joseph, and the genealogy is Joseph’s. and of course elements that were unknown to anyone in the Christian community, like Herod’s thoughts and schemes. In a sense, those first 2 chapters are pre-history, much as the early chapters of Genesis are pre-history.

I hope it doesn’t come across unnecessarily rude, but this kind of response is all too reminiscent of the responses I came to expect from my undergrad religion professors, or the kind of thing that drives me crazy in reading Bart Ehrman or Peter Enns… they would give some erudite, scholarly sounding argument for a standard critical position (late date of some book, some supposed irreconcilable contradiction, pseudopigraphal authorship of the pastoral epsitle, etc.)… but said argument wouldn’t stand up to a moment’s scrutiny or even basic common sense when examined… and when I’d ask them to explain or defend said argument from obvious counterevidence, there was just nothing there, and they couldn’t even begin to explain or defend the argument… For my professors and others I’ve interacted with, they were simply repeating arguments they heard, arguments they’d never bothered giving even a moment’s scrutiny because they supported the pet theory.

It was this very kind of experience that convinced me that so many of these erudite sounding arguments that didn’t hold water upon scrutiny were just blind adherence to a narrative on their part (I’m not accusing you of this, as in my discussions with you, you go out of your way to be fair to all sides and to give all positions a fair treatment).

The book you mentioned is $47 and only in paperback on Amazon, and I’m not going to spend that on a book to further the discussion, but if you want to share more specifics after you read it I’d be interested to engage… but I still find the idea preposterous on its face… and the other selection you referenced only deepens my skepticism…

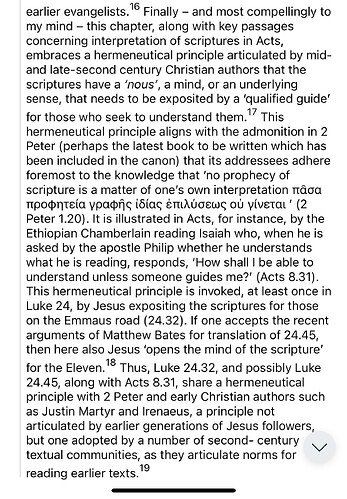

a hermeneutical principle articulated by mid- and late-second century Christian authors that the scriptures have a ‘nous’ , a mind, or an underlying sense, that needs to be exposited by a ‘qualified guide’ for those who seek to understand them…It is illustrated in Acts, for instance, by the Ethiopian Chamberlain reading Isaiah who, when he is asked by the apostle Philip whether he understands what he is reading, responds, ‘How shall I be able to understand unless someone guides me?’ (Acts 8.31).

Right. So the task of explaining Scripture so that its readers/hearers can better understand its meaning was a totally novel development of the church in ~150AD. ![]() : Converts to Judaism back in AD 30-40 would never have expressed interest in better understanding the Scripture they were new to reading, nor would first century Rabbis ever have spent time explaining Scripture.

: Converts to Judaism back in AD 30-40 would never have expressed interest in better understanding the Scripture they were new to reading, nor would first century Rabbis ever have spent time explaining Scripture. ![]() Paul never exposited Scripture in his letters, and Jesus certainly never explained the meaning of Scripture.

Paul never exposited Scripture in his letters, and Jesus certainly never explained the meaning of Scripture. ![]()

I may be missing the point or missing context, so I’ll withhold final judgment… nevertheless, this kind of argument exhibits the same level of absurdity that reminds me of the biggest whopper I ever heard, when Elaine Pagels claimed that the author of Revelation doesn’t say that Jesus died for our sins. How does one respond to such utter nonsense from a so-called scholar except to laugh?

Lets also not forget…the Ethiopian in Acts 8 wasnt reading the New Testament scripture…it hadnt been written into a “bible” at that time!

People so often conflate the reading of scripture in early christian church times with the entire bible cannon we have today. These werent scriptures back then…the scriptures were the Old Testament.

This is a part of the series - THE BIBLE – THE VERDICT OF HISTORY

His argumentation is that the whole NT except 11 verses is quoted by the Church Fathers in their writings before the 4th century.

His argumentation is that the whole NT except 11 verses is quoted by the Church Fathers in their writings before the 4th century.

Before the third century?

Maybe, I don’t know, I thought the guy made an interesting point.

I don’t even know if his math is sound.

Noone knows with great confidence when any of the Gospels were written. Mark could have been written before or after AD70, but I dont find many of the arguments for a post-AD70 dating particularly persuasive.

For example re the denarii coin, it is just as likely that the coin used was in fact a tetradrachm coin showing Tiberius and Augustus with highly objectional wording, at least to Jews, which is why they showed it to Jesus to get a reaction. But as Mark was writing from Rome and to a largely Gentile audience, he referred to it as a denarii as they wouldnt have known what a tetradrachm coin was.

Also, re Jesus referring to the destruction of the temple, he was clearly referring to his own body, but his accusers later perverted his words to claim he had threatened the destruction of the Jewish Temple. This was a major (false) accusation during his trial. I dont see how the Jewish Temple had to have already been destroyed for any of that to be understood. There doesnt need to be an ironic reading of the text.

I also think the principle of protective anonymity may have an influence on dating Mark. For example, unlike John, Mark does not name the specific High Priest involved in the execution of Jesus. He is simply referred to as the High Priest. Yet John names him. Is it because Mark was writing at a time when the family of Annas and his son-in-law Caiaphas had significant influence on the Jewish leadership, and Mark did not want to stir up unnecessary persecution by the Jews? By the time of John’s writing Annas and his family were irrelevant and so he was happy to name them and the evil they did. Annas’ family of HPs largely ended in the early 40’s, but assuming their influence continued for a few years, this could place Mark in the 50s or early 60s.

But even though some evangelical scholars think all the Gospels were written post-AD70, I think it is obvious the main reason for atheist scholars believing the same is due to Jesus’ predictions and so they dismiss out of hand that he could have predicted the destruction of the Temple and Jerusalem ‘within this generation’ in the 30s, therefore Mark etc must have been written after the fact. They do, after all, use exactly the same argument for maintaining that Daniel was written in the 2nd century BC, not the 6th.

Noone knows with great confidence when any of the Gospels were written. Mark could have been written before or after AD70, but I dont find many of the arguments for a post-AD70 dating particularly persuasive.

Correct, and it could even date as late as 90CE. Maybe that is why Clement of Rome may not quote of this supposed Roman text stemming from Peter’s companion a single time, yet appeals to the OT countless times. Kind of hard to imagine Mark was written 30 years earlier and carried the authority of Peter in Rome and Clement does not seem to even reference it. Or Mark could date to 40 CE and 13 is about the Caligula crisis. Or Clement to the 60s or Mark written elsewhere.

They do, after all, use exactly the same argument for maintaining that Daniel was written in the 2nd century BC, not the 6th.

Actually, they clam Daniel’s predictions all seem laser accurate until the 2nd century BC where they fall flat on their face going forward. This allows Daniel to be dated with uncanny precision for such an ancient book.

But even though some evangelical scholars think all the Gospels were written post-AD70, I think it is obvious the main reason for atheist scholars believing the same is due to Jesus’ predictions and so they dismiss out of hand that he could have predicted the destruction of the Temple and Jerusalem ‘within this generation’ in the 30s, therefore Mark etc must have been written after the fact.

The DSS at Qumran show plenty of people predicted the destruction of the Temple. This would in no way be novel or unique. Atheist scholars can think Mark is post 70 and Jesus predicted the Temple’s destruction. Maurice Casey was an atheist who dated it to ~40 CE. Most Biblical scholars are believers and most opt for a date slightly before or after the temple’s destruction. This really has little to do with atheism vs theism. The standard rule is a text is dated after the last event it mentions. So the only real question is, does Mark and his audience know the temple was destroyed? A strong case can be made it does but the lack of mention of fire and such and their imperfect line up could mean Mark dates before…

Whether or not Jesus predicted it is irrelevant. I have seen quite a few people claim its atheists rejecting the possibility of predicting events before they happen, but I have seen no one address the merits of Goodacre’s very weighty argument.

But as Mark was writing from Rome and to a largely Gentile audience, he referred to it as a denarii as they wouldnt have known what a tetradrachm coin was.

Zeichmann says this:

This anachronism of coinage is significant because the denarius is absolutely essential to the pericope in Mark; the emperor’s portrait prompts Jesus’ riposte to his opponents’ challenge. It is Caesar’s coin because it depicts his title and profile. If such coins were exceedingly uncommon for decades after Jesus’ death, it would stand to reason that the pericope in its Marcan form derives from that later period. The matter cannot be resolved by supposing that Mark accidentally named an incorrect denomination in narrating an otherwise historical anecdote: Syon notes that other coins with the emperor’s profile rarely circulated in prewar Judea—a policy of respectful of aniconism.19 One might therefore assent to Syon’s sugges- tion that “the author [of Mark], writing in the post-70 c.e. period—when denars were already common enough—assumed that denars had circulated under Tiberius as well.”20 This anachronism creates obvious problems for a prewar composition that locates Mark in the southern Levant.

But to your point, there is a lot of debate as to where Mark wrote. Syria seems to be just as viable as Rome now and the coin argument doesn’t work unless Mark wrote outside Rome. The author admits that in the article as I noted. Like countless other scholars, he rejects Roman provenance for GMark… Zeichmann:

The farther one locates Mark’s compo- sition from the southern Levant, the less plausible the following arguments become. Although they hold well for a compositional location in Ptolemais, Tyre, or Sidon, much of the present interpretation would be difficult to maintain if the composition of Mark is located in the city of Rome.

So If Mark writes in the Southern Levant, your apologetic is wrong. Zeichmann again:

Mark once again uses a Latinism, in this case δηνάριον to denote a specific monetary denomination—it is not a generic νόμισμα. Denarii were rare in the southern Levant, especially in Galilee, before Nero’s death in 68 c.e., which suggests that the pericope in its Marcan form derives from after that time.

For what its worth, Zeichmann also writes this:

This point must be emphasized: even though Judeans were subject to several taxes after the annexation of the territory in 6 c.e., none of these capitation taxes was collected via coin until the war. Fabian Udoh suggests that the widespread assumption that such taxes did exist largely continues due to the interpretive iner- tia on this particular pericope.24 It is common to suppose that Judeans were obliged to pay monetary taxes in the time of Jesus, a matter frequently asserted in the scholarly literature. Even cursory investigations of this claim, however, reveal that such arguments tend to be grounded in the taxation pericope in Mark 12:13-17 and its parallels taken as a historical reference to taxes of Jesus’ time. Udoh even quotes a number of prominent scholars of Roman imperial administration citing Mark 12:13-17 as their sole evidence for claims regarding Roman taxation (e.g., a one- denarius poll tax under Tiberius in Judea). NT commentators in turn cite these very classicists to inform their interpretation of the pericope, leading to inadvertent circular reasoning. Prewar evidence indicates that Judean taxes were largely exacted in kind, with coinage used in exceptional circumstances. Indeed, the econ- omy of the southern Levant was not even fully monetized during Jesus’ time; the widespread circulation and use of coinage in rural Judea was facilitated decades later by the postwar military occupation.25 This fact alone would have rendered any monetary collection an ineffective means of taxation.

Vinnie

Maybe, I don’t know, I thought the guy made an interesting point.

I don’t even know if his math is sound.

You can but not for a few centuries, there would probable be some significant differences in the text using Patristic citations and the argument is a bit circular because it already assumes we know what the text looked like. Figuring out what is a specific reference and what is from oral tradition is another matter as well. Extensive quotations are a few centuries removed.

Vinnie

Right. So the task of explaining Scripture so that its readers/hearers can better understand its meaning was a totally novel development of the church in ~150AD.

: Converts to Judaism back in AD 30-40 would never have expressed interest in better understanding the Scripture they were new to reading, nor would first century Rabbis ever have spent time explaining Scripture.

Paul never exposited Scripture in his letters, and Jesus certainly never explained the meaning of Scripture.

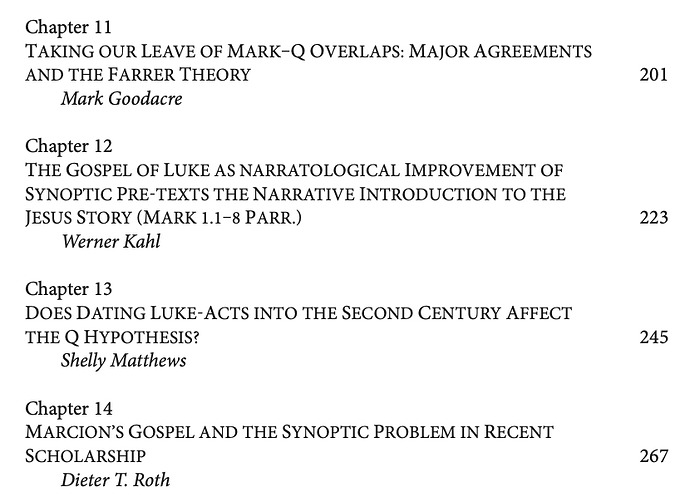

If that is your response I am guessing you are correct when you say “I may be missing the point or missing context”. The scholar is not claiming no one ever sought explanations for the meaning of scriptures, just that Luke fits in well with a second century hermeneutical change that they reconstruct as taking place. I would like too see the argument flushed out more before rejecting or laughing at it. I tracked down the quote. Its chapter 13 in the book: Gospel Interpretation and the Q-Hypothesis.

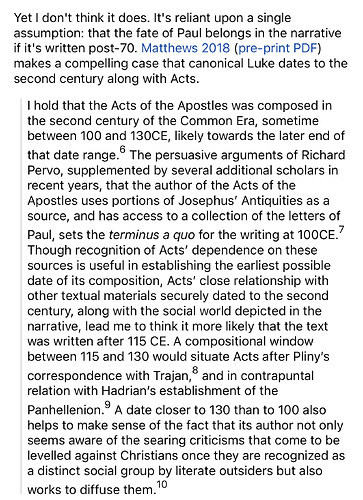

This is Shelly Matthew’s section on Dating:

Acts. I hold that the Acts of the Apostles was composed in the second cen- tury of the Common Era, sometime between 100 and 130CE, likely towards the later end of that date range.6 The persuasive arguments of Richard Pervo, supplemented by several additional scholars in recent years, that the author of the Acts of the Apostles uses portions of Josephus’ Antiquities as a source, and has access to a collection of the letters of Paul, sets the terminus a quo for the writing at 100CE.7 Though recognition of Acts’ dependence on these sources is useful in establishing the earliest possible date of its composition, Acts’ close relationship with other textual materials securely dated to the second century, along with the social world depicted in the narrative, lead me to think it more likely that the text was written after 115 CE. A compositional window between 115 and 130 would situate Acts after Pliny’s correspondence with Trajan,8 and in contrapuntal relation with Hadrian’s establishment of the Panhellenion.9

A date closer to 130 than to 100 also helps to make sense of the fact that its author not only seems aware of the searing criticisms that come to be levelled against Christians once they are recognized as a distinct social group by literate outsid- ers but also works to diffuse them.10

Luke 24. Close study of the final chapter of canonical Luke, and consideration of its programmatic function for the Acts narrative, has led me also to question the view that the date of this composition – at least the ‘final form’ of this final chapter11 – could lie in the mid-80s of the first century, as many scholars assume. While my arguments for dating Acts to the second century above rely heavily on work that has been published for some time now, and thus could be summarized briefly, this argument questioning the dating of the final chapter of canonical Luke requires more detailed elaboration here.12

There are a number of reasons to question the assumption that canonical Luke 24 was composed in the 80s, and to ask instead whether it might have reached its final form in close connection to the composition of the Acts of the Apostles sometime in the second century. One might note, for instance, the repeated obser- vations of John Alsup, in his study of source and redaction of post-resurrection appearance stories, that Luke 24 stands out among canonical gospels for the com- plexity of the relationships it sketches, and its overall compositional sophistication, and then ask whether it is likely for such compositional sophistication in tying together so many threads of early resurrection tradition to have been manifest already by 85 of the common era.13 One might ask about the obvious Eucharistic vertone in the Emmaus episode, where eyes are opened and Jesus is recognized after bread is blessed, broken and given (Luke 24.30–31) and ask how much time is required for such a ritual performance to be translated so neatly into this particu- lar narrative form. One might raise questions about relationships between Luke 24 and John 20, and even John 21 (widely accepted as a late appendix to the fourth Gospel), at points where divergences seem best explained by Luke’s dependence upon John, rather than vice versa.14

Though each of these questions merits further study, my own work on Luke 24 up until now has focused on the following two distinctive aspects of Lukan resurrection narratives which suggest a late dating for the redaction of this mater- ial: first, how Luke 24 (and Acts) approach the question of scripture interpretation; second, how fleshly resurrection in Luke 24 (in tandem with assertions pertaining to fleshly resurrection in Acts) function to authorize exclusive claims pertaining to the twelve apostles as authoritative witnesses to the resurrection.

Consider first the question of how Luke 24 treats the matter of scripture fulfil- ment and scripture interpretation. The three scenes in Luke 24 – the report of the empty tomb, the appearance to the travellers on the Emmaus road and the appear- ance to the eleven and those with the eleven – when taken together, function as the most expansive assertion of proof-from-prophecy of any canonical Gospel. The proof-from-prophecy claim here is expansive not just in acknowledging a tri- partite division of Hebrew Scriptures – the law, the prophets and the Psalms (Luke 24.44) – but also in asserting that the events in the life of Jesus fulfil the scriptures in their totality.15 Further, the narrative of a post-resurrection appearance to the apostles, in which Jesus teaches the apostles to read scripture in a manner enab- ling them especially to understand how Jesus’ suffering fulfils scripture, is a trad- ition Luke shares not with other canonical gospels, but with the apology of Justin Martyr, demonstrating that with respect to this idea Luke is in the orbit of the apologists, rather than the earlier evangelists.16 Finally – and most compellingly to my mind – this chapter, along with key passages concerning interpretation of scriptures in Acts, embraces a hermeneutical principle articulated by mid- and late-second century Christian authors that the scriptures have a ‘nous’, a mind, or an underlying sense, that needs to be exposited by a ‘qualified guide’ for those who seek to understand them.17 This hermeneutical principle aligns with the admon- ition in 2 Peter (perhaps the latest book to be written which has been included in the canon) that its addressees adhere foremost to the knowledge that ‘no proph- ecy of scripture is a matter of one’s own interpretation πᾶσα προφητεία γραφῆς ἰδίας ἐπιλύσεως οὐ γίνεται’ (2 Peter 1.20). It is illustrated in Acts, for instance, by the Ethiopian Chamberlain reading Isaiah who, when he is asked by the apos- tle Philip whether he understands what he is reading, responds, ‘How shall I be able to understand unless someone guides me?’ (Acts 8.31). This hermeneutical principle is invoked, at least once in Luke 24, by Jesus expositing the scriptures for those on the Emmaus road (24.32). If one accepts the recent arguments of Matthew Bates for translation of 24.45, then here also Jesus ‘opens the mind of the scripture’ for the Eleven.18 Thus, Luke 24.32, and possibly Luke 24.45, along with Acts 8.31, share a hermeneutical principle with 2 Peter and early Christian authors such as Justin Martyr and Irenaeus, a principle not articulated by earlier genera- tions of Jesus followers, but one adopted by a number of second-century textual communities, as they articulate norms for reading earlier texts.19

Second, consider how Luke 24 and Acts closely connect the appearance of the resurrected Jesus in flesh and bone to the authority of the twelve apostles. In Luke 24 Jesus appears before the 11 (and those with them), saying ‘touch me and see; for a spirit does not have flesh and bones as you see that I have’ (24.39b: ψηλαφήσατέ με καὶ ἴδετε, ὅτι πνεῦμα σάρκα καὶ ὀστέα οὐκ ἔχει καθὼς ἐμὲ θεωρεῖτε ἔχοντα).

A first clue signalling Luke’s awareness of an internal and ongoing quarrel con- cerning the nature of the risen Christ, as Daniel Smith has noted, comes from the fact that Jesus is said to interrupt and clarify a resurrection debate already in pro- gress, even among those within the inner circle. Before he asserts that he stands before them in flesh and bone, Jesus is said to perceive the ‘disputes’ [dialogismoi] that arise in the hearts of the eleven (24.38) concerning the nature of what they are seeing.20 As further proof that he stands before them in flesh, he eats the grilled fish (24.41–43).21

This is the only explicit reference to Jesus’ fleshly resurrection in all of the canonical gospels, already a clue that Luke 24 may be a participant in a debate best placed in the third generation of Jesus followers.22 Unless one grants an early date to the composition of Barnabas, indications of contests concerning the fleshly substance of the resurrected Christ in the apostolic fathers are generally dated from the Trajanic period and beyond.23 A stronger case may be mounted for this later window of time if one recognizes that the assertion of Luke 24 that the resur- rected Jesus stands in flesh is closely tied to his assertions pertaining to apostolic authority.

As I have argued elsewhere, canonical Luke 24 sets out a programmatic state- ment on the connection of the appearance of the resurrected Jesus in the flesh to the exclusive authority of the eleven (soon-to-be-twelve) apostles/witnesses. This connection is underscored in the inaugural speeches of both Peter (2.31–32) and Paul (13.31,37) in which assertions that Jesus’ flesh was not corrupted through the process of death and resurrection are closely linked to authorization of the twelve as exclusive witnesses to that resurrection.24 This connection is also signalled in the story of the restoration of the twelve in Acts 1.12–26, and most elaborately in Peter’s speech before Cornelius:

[God] made him manifest not to all the people, but to those witnesses who were foreordained by God, to us, we who ate and drank with him after he rose from the dead. And he commanded us to preach to the people and to bear wit- ness that this is the one ordained by God as judge of the living and the dead. To him all the prophets bear witness [καὶ ἔδωκεν αὐτὸν ἐμφανῆ γενέσθαι, οὐ παντὶ τῷ λαῷ, ἀλλὰ μάρτυσιν τοῖς προκεχειροτονημένοις ὑπὸ τοῦ θεοῦ, ἡμῖν, οἵτινες συνεφάγομεν καὶ συνεπίομεν αὐτῷ μετὰ τὸ ἀναστῆναι αὐτὸν ἐκ νεκρῶν. Καὶ παρήγγειλεν ἡμῖν κηρύξαι τῷ λαῷ καὶ διαμαρτύρασθαι ὅτι οὗτός ἐστιν ὁ ὡρισμένος ὑπὸ τοῦ θεοῦ κριτὴς ζώντων καὶ νεκρῶν τούτῳ παντές οἱ προφῆται μαρτυροῦσιν]. (10.40b–43a)

Consider the weighty assertions pertaining to early Christian authority and proc- lamation condensed into this succinct formula. The role of the twelve as witnesses is said to have been foreordained (προκεχειροτονημένοις). In yet another instance of the expansive nature of proof-from-prophecy in Acts, Peter claims authoriza- tion to preach a message to which all the prophets testify (10.43). This text employs the (pre)-creedal affirmation that Jesus is judge of the living and the dead (κριτὴς ζώντων καὶ νεκρῶν) a phrase it shares with many turn-of-the-century writings, including 1 Peter, Barnabas, 2 Timothy, 2 Clement, and Polycarp.25 Finally, the exclusive status asserted for the twelve apostles owes to their having witnessed the resurrected Jesus in the flesh, proof of which lies in their having eaten and drunk with him.26

It is my contention that the groundwork supporting these arguments in Acts for the exclusive authority of the twelve to speak for Jesus because they saw Jesus in the flesh (Acts 1.12–26; 2.31–32; 10.40–43; 13.31,37) is laid in canonical Luke 24. Elaine Pagels recognized long ago that Luke’s particular apostolic concept was used from the second century onwards to validate the apostolic succession, and to combat the authority of visionaries.27 My argument here tweaks that of Pagels by suggest- ing that Luke’s writing serves that purpose so well, not because he anticipated an argument that would take place only among future generations of Christians, but because the final redaction of Lukan materials takes place in the second century itself, when these debates concerning fleshly resurrection and authority arise.28

In sum, the arguments crafted in Luke 24 pertaining to scripture interpretation, fleshly resurrection and exclusive apostolic witness, which are subsequently devel- oped in Acts, lead me to the conclusion that the final chapter of canonical Luke also received its final form in the second century. Though these conclusions have been reached independently from the recent revival of interest in the relationship of canonical Luke to Marcion’s Evangelion I turn now to the question of how Marcion’s Gospel (and/or Marcionitism29) affects my own thinking about Lukan materials.

Judging by all the lengthy footnotes I omitted and the complexity of this argument, I don’t think your mocking and laughing emojis are a good response. I’m not even endorsing this. It’s just one of a number of reasons highly educated Biblical scholars increasingly see Luke as second century. Remember, Luke also starts with “Many have undertaken”, which is a more difficult sell in the 60s…than 80s or 100s.

Also, if you want deeper insight into ‘nous’ Matthews claims to be highly indebted to this work:

BATES, MATTHEW W. “Closed-Minded Hermeneutics? A Proposed Alternative Translation for Luke 24:45.” Journal of Biblical Literature, vol. 129, no. 3, 2010, pp. 537–57. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/25765951. Accessed 23 Aug. 2024.

I just went and skimmed it. Jstor allows free access to 100 articles a month so you could read it.

The scholar is not claiming no one ever sought explanations for the meaning of scriptures, just that Luke fits in well with a second century hermeneutical change that they reconstruct as taking place.

Perhaps it is the “fool me once…” thing… but I have seen this kind of argumentation far, far too often, claiming that “XYZ fits within a second century framework” but where said scholar either fails to notice, or conveniently neglects to acknowledge, that said data also fits just as perfectly (if not moreso) within an early to mid first century framework… and then these scholars become such a devotee of their pet theory to the degree it blinds them to seeing what should be obvious in the text itself…

Again, this sounds to me too much like the enormously erudite scholarship of Elaine Pagels, who cataloged all sorts of deep and layered alternate understanding of Revelation’s “real” meaning, and the development of the author’s theology, where he fit (and conflicted) within the divergence of early Christianity, etc… but she got so caught up in the layers and theories and inventions and hypothesized reconstructions that she could no longer even read what was on the pages of Revelation itself, and reached unimaginable levels of absurdity. How in the world else does one make of her utterly asinine claim that the author of Revelation “doesn’t even say Jesus died for our sins”?

It is this very kind of reasoning that Lewis was reacting to when he described it so well… “These [scholars] ask me to believe they can read between the lines of the old texts; the evidence is their obvious inability to read (in any sense worth discussing) the lines themselves. They claim to see fern-seed and can’t see an elephant ten yards away in broad daylight.”

So this scholar can read between the lines and see so clearly how well the idea of “teaching Scripture” fits within a second century context. But this scholar can’t seem to notice that it fits perfectly within a first century context. And I am expected to trust their judgment?

Echoing Lewis, "whatever these [scholars] may be as biblical critics, I distrust them as critics - they seem to me to lack literary judgement; to be imperceptive about the very quality of the text they are reading.

Judging by all the lengthy footnotes I omitted and the complexity of this argument, I don’t think your mocking and laughing emojis are a good response.

I stand by my laughter, for whatever it is worth. I’ve just seen this far too often. You should see how well Elaine Pagels book on Revelation was researched, and still the only legitimate response I can conceive of to her claim about the author not saying Jesus died for sin is to laugh.

And making an erudite claim about how “teaching Scripture” better fits in the second than first century is, well, laughable.

Another observation, though… all these erudite reconstructions (the very type that Lewis was critiquing) all also depend on superimposing multiple hypotheses… making the assumption that Jesus did no such things as were recorded, and they were all invented out of whole cloth for the deceitful agenda-driven purposes of the early church. This Lewis rightly observes is really multiplying baseless hypothesis upon baseless hypothesis, even if “done with immense erudition and great ingenuity.”… Lewis’s example that is not very different than the one above…

Bultmann says that Peter’s confession is an Easter story projected backward into Jesus’ lifetime. The first hypothesis is that Peter made no such confession. Then, granting that, there is a second hypothesis as to how the false story of his having done so might have grown up… You see that if in a complex reconstruction you go on thus superinducing hypothesis, you will in the end get a complex in which, though each hypothesis by itself has in a sense a high probability, the whole has almost none.

So in the section you quote above the author so eruditely observes, “One might ask about the obvious Eucharistic vertone in the Emmaus episode, where eyes are opened and Jesus is recognized after bread is blessed, broken and given (Luke 24.30–31) and ask how much time is required for such a ritual performance to be translated so neatly into this particu- lar narrative form.”

Or, Luke may have recorded this because it actually happened? Has this scholar even considered this as a possibility? (Asking for a friend…)

The fact that this possibility is not even given a moment’s consideration, in deference to his hypothesis-upon-hypothesis-upon-hypothesis reconstruction… And you notice this scholar is already assuming and apparently totally sold out to the correctness of his (baseless) hypothesis (the only really open question seems to be as to how long it took for said reconstruction to happen, not whether it happened)… This is what engenders my deep skepticism - it is what betrays to this reader that said scholar is blind to any other interpretation except those which further the pet theory. And the fact that, in examining these texts, the author has a priori dismissed even the possibility that actual history was preserved and recorded means that, well…

We know in advance what results they will find for they have begun by begging the question

So I am baffled how anyone who affirms Christ’s miraculous powers in general, can give any credence to any arguments that presuppose that Christ did not have the power to have made predictions of the future?

I don’t believe Jesus had any supernatural powers and I still don’t give any credence to these arguments.

All it took to predict the destruction of the temple was an awareness of the socio-political situation and how Rome always dealt with things like that eventually.

Jesus is 100% human and 100% God. God is not confined to human theological definitions – God can be whatever He chooses.

100% human means limited to human abilities, and even Jesus said He could do nothing but see what the Father was doing. He said we would to much greater things than He.

For instance the language of legion in Mark 5:1-20 only works after the War, since before the War the military in Palestine and the Decapolis was not legionary. As an analogy, a story wherein a demon named “Spetsnaz” is exorcized from a Crimean denizen should strike the reader as anachronistic in its politics if depicted as occurring in 2010; one would assume the story had been written after the Russian annexation of Crimea in February 2014, in which the aforementioned special forces were active.

This is totally bogus: it rests on the assumption that no one in Palestine had ever heard of a legion before, and that no one in the Crimea had ever heard of Spetznaz. Both of those are ludicrous. In the second case, one would only be justified in saying it was written most likely after the second world war when Spetsnaz units became common knowledge, and in the first only that it was written most likely after 66 BCE when Pompey conquered the region.

The coin argument has far more substance.

why would I similarly accept similarly faulty methods when the conclusion is similarly interconnected with the question of the miraculous?

Though as some of Vinnie’s citations show, dating after 70 is not necessarily anti-miraculous.

The abrupt end of Acts, along with the absence of major events that would be expected to be included had Luke known of them, though not conclusive, is very compelling evidence to me that the book was indeed composed (or completed?) right near that time.

Though the argument I’ve heard that Luke would certainly have written of Paul going to Spain since that would complete the list of nations in the Genesis “Table of Nations” isn’t helpful since it assumes that Luke knew of that and considered it important.

when he had no issue noting the death of James the apostle as well as Stephen’s death.

But they were killed by those primitive Jews, not urbane Romans.

The fact that there exists in a work a very natural ending, but the work continues to another ending, is not by itself evidence of later editing by a different party.

As evidence by Paul’s “finally” in some letters being followed by quite a lot of text!

Today a writer would back up and rewrite to get everything in before the end (unless it was for a TV shows), but when writing materials are far from cheap it’s not so simple.

(as there is for the woman caught in adultery?)

Oddly, that appears in a few different places in a few different manuscripts.

And all of the manuscripts show accidental and deliberate scribal changes.

Including some that appear to have been marginal notes by someone studying the text that got incorporated by a later scribe who thought them emendations.

I read it several years ago and found The Earliest Christian Artifacts by Larry Hurtado interesting. It is copyrighted 2006 and so is probably out of date.

It’s unnerving to me sometimes just how much of what I learned in grad school is out of date! It’s something that makes people like Dr. Michael Heiser so great; they keep up on things and say when something they said before has been found to have been different.

And this is getting long; time to start another post!

Plenty of evidence for textual corruption before the manuscript record and plenty of sources to read about the potential redaction of John. Parts of it seem greatly disordered. But I’d rather not start going into detail on multiple issues at once.

I took an optional class on John and one project was to trim it down to just the “signs” episodes. We argued about where to cut the text, but it was surprisingly easy to read as having been written that way originally. I liked the idea that John wrote it that way first, then filled in between with other material.

I also like the hypothesis that the author was a younger John who lived in Jerusalem and was only with Jesus when He was in that city (I think Richard Bauckham argues for that).

But I’d rather not start going into detail on multiple issues at once. The dating of the synoptics/Acts is already time consuming.

![]()