This is discussed in several YEC websites. Try CMI, AIG, and quite recently on EN and ID the Future.

Pick an article that you like and we can start a thread on it if you like.

I’ll grab one here: Medical Considerations for the Intelligent Design of the Recurrent Laryngeal Nerve | Evolution News

What all of them have alike are ‘well it does a lot of stuff now’ or ‘humans who are born without the bottom part tend to struggle severely.’ None of them actually address any reason why or how this actually came to be, nor can one refute the scientific explanation other than ‘well it does lots of stuff today.’ Of course it does! It’s a nerve! And if you changed it today without changed all of the tinkered parts around it any organism would struggle because all of the other parts have been tinkered with by natural selection and genetic variation with the constraint of a fish like laryngeal nerve.

The more interesting question is surely why the fairly common genetic variation of a direct left laryngeal nerve has not been conserved in evolution. We know evolution can do it, but we also know it hasn’t kept doing it.

Kind of like the high prevalence of polydactyly mutations despite the near universality of the pentatadctyl limb throughout most vertebrates in every situation from burrowing to flying.

In other words, variation and natural selection are the very last processes you’d expect for these phenomena. Common descent - that’s more probable, or at least is once you’ve explained why the ability of even humans to produce a direct laryngeal nerve variation relatively commonly isn’t selected and preferred by common descent.

Of course, the change in nerve route would have to confer some advantage to be conserved, and I really know of no real reproductive advantage it would have. If you get hoarse when the mediastinal mets from lung ca presses on the nerve, it really does not affect future generations. What we see as an inefficient design may be the best way to achieve the end result given the constraints of biology.

So, as you said, common descent is probably the best explanation.

Indeed - but that weakens the “Bad design” argument considerably.

Is it common? Has it been common for the past three hundred million years or so? Let me know what sources you are looking at as all I could find was something like this:

Non-recurrent laryngeal nerve (NRLN) is a rare anomaly which is reported in 0.3%-0.8% of people on the right side, and in 0.004% (extremely rare) on the left side.

Apparently though, the bulldog of anti-evolution arguments on this topic has been Wolf-Ekkehard Lönnig who is quoted repeatedly in Evolution News and other similar sites. Part of his argument is actually similar to your argument where he advocates for a ‘law of recurrent evolution’ which I could find nowhere referenced except by himself and articles on EN - which basically puts an extreme limit on what can occur over long periods of time variation of traits. I’m not sure of his intent or motives of course, but to an outsider it appears that he made up a law of biology so that he can use the law he made up against any arguments regarding the evolution of the laryngeal nerve. He also has a book on The Evolution of the Long-necked Giraffe.

I think this is best visualized from a ‘fitness landscape’ perspective. A non-recurrent nerve would represent a maximum peak if designed from scratch of optimal design and a recurrent nerve would not. However, evolution doesn’t produce anything from scratch but only rather tinkers with existing material. So what kind of starting point did evolution have with the laryngeal nerve? One similar to how it is in fish where it is looped around the aortic branch. With this starting point in an ancient common ancestor - you would not have such big jumps and rerouting of nerves as slight variations would still look very much the same. With this starting point, this circulatory system evolved together, with slight variations here and there. Today, to change one of the major parts would be catastrophic to the organism without changing all the other parts around it - and this would not be selected for, despite it being a global maximum in regards to efficiency of design.

But 0.004% is common in evolutionary terms - adds up to about 240,000 folks worldwide, by my poor maths - sufficient, surely, to have become fixed at some stage if it were “a better design”. In the case of many adaptive traits, we’re assuming mutations that occurred only once - and whales are renowned for their juggling an entire body plan in just a few million years to colonize a new niche, in comparison to which shifting the course of a nerve for better efficiency all round seems small beer.

I spoke from a medical background (small print in anatomy texts - the recurrent laryngeal nerve gets taught because of Phil’s reason of complications of Ca bronchus, but also because idiot surgeons might otherwise slice through it and turn people into mutes), but there seems no reason why the same, or a similar, mutation would not occur in other vertebrates, including giraffes.

But it happens, 4 in 100,000 times in humans - and it’s survivable, or it would not be in the anatomy texts as a variant. Whether it’s linked to other ill effects genetically I don’t know - polydactyly is, but not enough to prevent whole tribes in S America inheriting it. But once again, entire bauplans need to change for many adaptations - wings for flight, for example. So whilst one can plausibly invoke fitness landscapes to say why one set of things won’t happen, it’s absurd to invoke the same explanation when equally big things do happen.

How do we know that something isn’t happening? Perhaps that 0.004% is “explosively taking over” on an evolutionary timescale which means that (no other factors interfering) it might be the dominant situation in another few hundred thousand or some millions of years.

Of course what seems a lot more likely is that it might be “small beer” compared to a lot of other environmental changes that happen meanwhile, necessitating much larger adaptations for reproductive / survival fitness.

Well, Merv, the population geneticists can argue about that - but the recurrent laryngeal nerve has done staunch service since time immemorial. If it’s taking natural selection that long to put on the “to do” list then, once again, the bad design argument that brought it into this thread really doesn’t hold water - or is that the badly designed female bladder?![]()

It is? In a population of less than 25,000 - this would come out to a fraction of a person. So perhaps historically nobody ever got this 0.004% mutation in the first place and it certainly would not have been even a possibility in the fitness landscape as it was starting very far away from what would be “efficient” hundreds of millions of years later.

Let me try to summarize what you are saying and let me know if I’m misunderstanding you. Are you trying to argue that natural processes would have selected for a more efficient design by now and thus this nerve is better evidence of a non-common descent/supernatural creation type of model? Since it has not it doesn’t make sense to argue that this is ‘bad design?’

I personally don’t like the argument from “bad design” but rather am trying to focus on “evidence of common descent” that does explain the pattern of the laryngeal nerve quite well.

Let’s use an analogy.

In your living room you set up a TV just 2 feet from an outlet. In order to get power to the TV you run a 50 foot extension cord across the room, around your couch, wrap it around the end table a couple of times, and then plug it into the outlet that is just 2 feet away from the TV. Is that a bad design? Yes. Good design is using a three foot power cord to plug the TV into the outlet that is 2 feet away using a direct route.

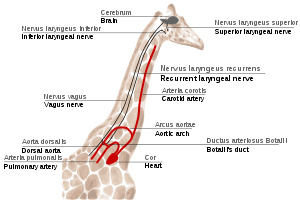

That is similar to how the recurrent laryngeal nerve is set up in tetrapods. The nerve exits the spinal column very close to the larnyx, but instead of going straight into the larynx the nerve goes down into the chest cavity, loops under the aorta, moves back up through the chest cavity, and then terminates in the larynx. In the giraffe this circuitous route adds multiple unnecessary meters of the length of the nerve. This is bad design.

Added in edit:

This picture illustrates the extra 15 feet that the recurrent laryngeal nerve has to travel in the giraffe.

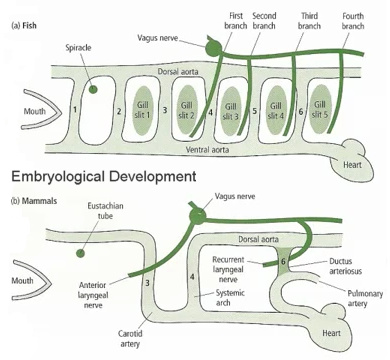

To be clear, the nerve does take a direct route in fish. The evolutionary explanation for why the nerve takes such a circuitous route is that some of the gills slits found in fish evolved into the tetrapod larynx. What we kept was the ancestral developmental patterns which required the laryngeal nerve to loop under the aorta which is the same route it takes in fish.

So the path of the laryngeal nerve was conserved, and it is this conservation that results in its long path through the chest.

No - you put words in my mouth when I explained what I meant quite clearly. I’m just saying that it’s useless as an example of bad design (the subject of the thread, i thought), and it has grave shortcomings as an example of adaptive evelution, or a lack thereof. In fact, apart from the trivial likelihood of its being linked to common descent (does anyone on the thread dispute this? I haven’t checked), it tells us nothing much about whether it is good, bad, or indifferent fiunctionally, or why it’s conserved.

T aquaticus makes one of my points well, with his giraffe diagram (quite unnecessary for me, really, with a degree in medicine - I’ve actually seen the thing during surgery - and I dissected the damned dogfish at school. But hey, there are maybe people without a knowledge of anatomy here).

You presented a generic picture of a fitness landscape to show how these could plausibly explain why the giraffe, say, was unable to fix a direct left laryngeal nerve together with the other changes necessary to make it work. Your fitness landscape, I take it, was not derived from actual laryngeal nerve data - it’s a just so story that would, if it happened to be true, account for the persistence of the LRLN throughout evolution. Maybe it is true - but nobody actually has evidence.

Then T aquaticus educates me with a picture of a giraffe - which in order to acquire its long neck, has created an eigth cervical vertebra, boosted its systolic pressure to something that would give us a stroke, yet evolved mechanisms keeping it steady whether it raised or lowers its neck. It has muscular arteries in the neck, a special series of valves, changes to oesophagus, adaptations in respiratory rate to adapt to a huge dead space, and a whole host of other surprising adaptations which - as far as the fossil record goes - occur together in the very first long-necked giraffe, without any gradation of previous forms as regards neck length. We know what a giraffe is like, but how all those changes were coordinated in evolution is unknown.

But I can explain it easily! I could use your fitness landscape diagram to describe that, in this particular case, all the peaks (and the fitness peaks of many height-related changes elsewhere in the body) were contiguous and enabled a complete anatomical arrangement of nearly everything in the neck… except the recurrent laryngeal nerve, for reasons we can explain by your previous post.

So without actually knowing anything about the evolution of the giraffe, we confidently say that it has a long laryngeal nerve because some kind of fitness landscape prevented it changing, and it has coordinated changes in every other feature of the neck because some undefined other kind of fitness landscape allowed it all to change.

One solution answers any question and we don’t actually know any more at the end about the actual reasons the form of the nerve is conserved. Except that some folk, at least are sure that it is clear evidence that God wasn’t around in the process because the one thing we do know in all this ignorance is that it’s a bad design.

The point is that the RLN takes the same path in both fish and mammals with respect to developmental biology. For mammals, this path was inherited from our fish ancestors. It doesn’t make sense that if humans were designed from scratch that a designer would loop the RLN under the aorta, as if to preserve an evolutionary history that never occurred.

You seem to be under the impression that giraffes went from short neck to modern long neck all in one step. I see no reason why they couldn’t have a gradually elongating neck over time where these other features could co-evolve.

What we do know is that it is conserved. Natural history and developmental biology is full of evolutionary contingencies that reflect evolutionary lineages. For example, cetacean embryos grow limb buds that are absorbed and disappear later in development. Manatees have toe nails on their flippers. The pharyngeal pouches in both fish and human embryos are obviously related, with these pouches evolving into the larynx and other structures in humans and gill slits in fish. Developmental pathways tend to become entrenched and are difficult to change. The changes we do see are usually in the later stages of development.

Is there anybody participating in the conversation here at pains to deny common descent? Who are you talking to? I doubt that anyone here denies CD, though this is subject to correction of course.

I for one am glad, @Jon_Garvey , to have the giraffe (and TV chord!) examples as this was all new to me. So I do appreciate the exchange between all of you more knowledgeable people here in that regard, especially your part in it, Jon, to give what I think remains a much needed (and I think still unanswered) challenge to the whole “whatever we know or don’t know – we know it wasn’t the way an efficient God should do it” industry that does look suspiciously weak to me too; extension chord analogy notwithstanding. All that tells us (and I grant that it does illustrate it well) is that if a human-like engineer with a boss and a schedule to keep was to construct a human all in one clean blow from scratch (ground-up custom design), then he probably would opt for the direct nerve connection. But as God did not (so far as any of us here are concerned --right?) build up humans like a human would, the whole question about “good design” or “bad design” from that perspective becomes a moot and rather ridiculous point. At least that is the take on all this that I will here own, even if others of you here might not.

Added: Maybe a better design question would be: if an engineer were tasked to design an entire ecosystem in one fell blow that would eventually spawn a multitude of creatures and even culminate with thinking, talking, communing humans and time and space for the task is not limited to the miserly portions we humans are obliged to work within … then how did the designer do? This would still be futile exercise as well since we still have more ignorance than knowledge to work with; and the usual objections about the many species dying off before we even got here will be trotted out as evidence that some designer was still asleep on the job. But for those of us who haven’t pre-determined our conclusions in that regard, we can also just as easily see a breathtaking grandeur of design to the whole sweep of it too --or at least the little part of that whole sweep that our own limited visions afford to us.]

…and … with yet more edits. I think I’m done now!

I don’t think anyone can actually say what or what would not be ‘good’ or ‘bad’ design outside of their own opinion. In the same way that I cannot accept (outside of a pure faith choice) that the cosmos look ‘designed’ as I wouldn’t know what a ‘designed’ vs. ‘undesigned’ cosmos looks like.

In a scientific sense do you mean or in a broader philosophical/theological sense? If in a scientific sense, then I’d disagree as in “well this time it could be God who looped that nerve around, this is our best explanation as of now.” Like this paper I agree with in a theological sense but agree with the retraction in a scientific sense:

The Design Aesthetic argument is rather subjective, but it is an argument that ID proponents make a lot. They try to make claims about how beautifully this or that adaptation is designed, and argue that it must be intelligently designed because of the beauty or efficiency of the design. The counter-argument is bad designs. I think this is where a lot of the discussion comes from.

There is also what I call the Dobzhansky argument (i.e. “Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution”). If you understand developmental biology and evolutionary history, then the recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN) makes a lot of sense. The RLN is an example of a wonky arrangement of parts that is caused by a stochastic and historically contingent processes. The RLN is also what you get when you select for performance instead of design which is what natural selection does.

As to the sweeping grandeur of the whole thing, that is definitely in the eye of the beholder and beyond the realm of science.

Agreed.

Broader philosophical/theological sense (if I properly understand your distinction.)

That was one of the lines I edited, though my edit was obviously after you were crafting your reaction here. Instead of referring to it as the “…‘we know it wasn’t God’ industry”, I changed it to the " … we know it wasn’t the way an efficient God should do it’ industry…". Much more of a mouthful, but I made the change with you in mind since I know you don’t deny God’s involvement at a theological level. And possibly none of us here do except @T_aquaticus, but even his denial is not so much a strong one as it is an agnostic “haven’t seen the evidence for it yet” kind.

I just don’t think science has any handle on what would make for good or bad design from the perspective of eternal Deity. Science can only speak to human perspective engineering. I guess that makes me agnostic toward both the I.D. and the anti-I.D crowd. I think both sides of that battle are fighting with imaginary weapons.

…and I will own up to my own pre-determined conclusion to see the “glass half-full”, so-to-speak. I think I agree with everything you posted up there at the same time that I posted my reply above. Thanks again for the nerve explanations and analogies.

It is interesting that one of the more recent ID papers uses human based software design to argue for intelligent design in biology.

This is why the Dobzhansky argument is the better argument, IMHO. It gets away from what we humans deem good or bad design and focuses more on positive evidence for how something was designed.